Unemployed Californians to get an extra $600 in weekly benefits starting Sunday amid coronavirus crisis

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — Californians struggling to find work will receive an extra $600 in weekly unemployment benefits from a federal stimulus package starting Sunday, Gov. Gavin Newsom said, as a deluge of 2.3 million new claims in the last month has the state struggling to get payments to those who have just lost their jobs.

The additional relief money approved by Congress means California’s average weekly benefit of $340 will be boosted to $940, while those who get the maximum weekly state benefit will see checks increased to $1,050. The higher benefits will last for four months.

The first payment is going out Sunday to those with already processed claims and is for the week ending April 11. The payments will be credited to state Employment Development Department debit cards.

“Many Californians are feeling the effects of this pandemic, and this added benefit is very important to our workers so they have needed resources during this difficult time,” Newsom said in a statement Thursday.

Newsom said the 2.3 million new unemployment claims processed in the last four weeks are more than all the claims filed in 2019. The state paid nearly $684.3 million in unemployment benefits in the last month. For the week ending April 4, the Employment Development Department processed 925,450 claims, which is a 2,418% increase over the same week last year.

“That’s tremendously significant,” state Sen. Jerry Hill (D-San Mateo), who chairs the Senate labor committee, said of the larger payments. “That will make the difference for people — whether they can make it or not in this state.”

But the state is seeing a storm of complaints from newly unemployed workers who have been unable to get through to the Employment Development Department by phone for help in filing applications. In response, state lawmakers called Thursday for the agency to immediately expand call center hours beyond the 8 a.m.-to-noon daily window currently provided.

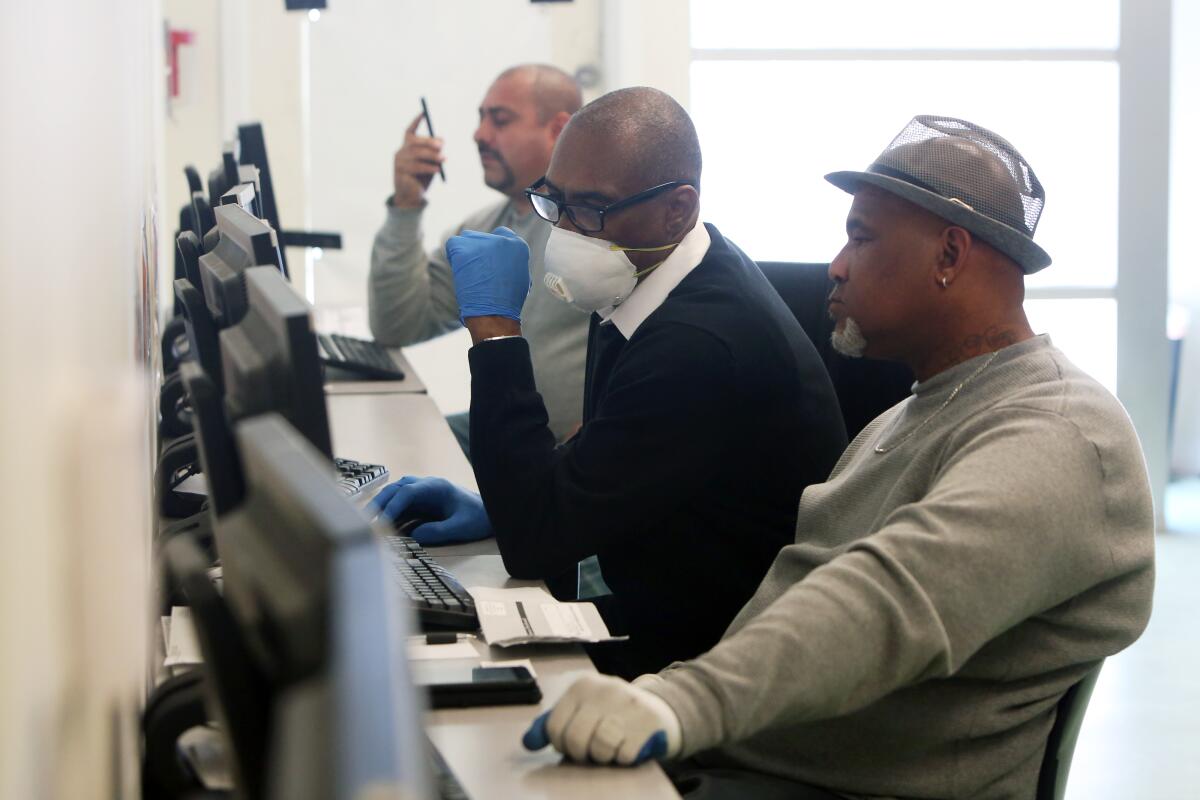

These are some of the unusual new scenes across the Southland during the coronavirus outbreak.

The economic damage inflicted by the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed other flaws in California’s program to help the unemployed, including state benefits that have not kept up with inflation and a shortage of reserve funds that could force the state to borrow billions of dollars from the federal government to pay out claims.

The state is also still struggling to set up a system to implement a portion of the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act that for the first time will provide jobless benefits to contract and furloughed workers and those in the gig economy. Those checks may still be weeks away.

“It’s a perfect storm,” said Carole Vigne, a staff attorney for the group Legal Aid at Work, which provides free services to low-income people seeking help with employment issues. “There is just no way an agency that size can handle this immediate influx. I would anticipate some pretty long delays despite their best efforts.”

Newsom said this week that he is aware of problems involving the processing of so many new claims.

“We are trying in real time to improve our capacity to deliver,” he said during a news briefing Tuesday. “Obviously we all have to do more and do better to meet the increased inquiries and the increased applications.”

Numerous unemployed Californians have complained on social media that they, or others they know, have been unable to reach the EDD by telephone to file new claims and for help with problems that prevent them from filing online.

San Fernando Valley resident John Muscarnero, who recently lost his job in the food service industry, said it is baffling that EDD call centers are only open four hours a day and that calls end up with long waits and without a live person answering.

“I called dozens of times. I never got through,” said Muscarnero, who has been unable to untangle the red tape involving his claim for jobless benefits. “It is the most frustrating and punitive process.”

He said he is having to choose between paying his rent and other bills including his car payment.

“The level of anxiety is through the roof,” he said.

Downtown Los Angeles resident Fernando, who spoke to The Times on condition his last name not be used, struggled to file a claim after he lost his sales job with a cellphone company. He said he called the EDD more than 90 times before he finally got a person on the phone who helped him process his claim.

“It’s an unfortunate situation,” he said. “Someone who got laid off is not going to be able to pay their bills, buy groceries, pay their rent.”

Labor law and resources for those affected by coronavirus crisis.

Opening phone lines for just four hours a day is not acceptable, said Hill, who is chairman of the Senate Labor, Public Employment and Retirement Committee, which oversees the EDD.

“They should go 12 hours a day,” Hill said. “The phone [line] is the crucial part of the process. If you can do it online you have solved your problem, but if you can’t do it online for one reason or another you are almost in hell because there is nothing you can do unless you talk to someone.”

Assemblyman Jim Patterson (R-Fresno) wrote to Newsom on Thursday to ask that EDD phone hours be extended to 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. on weekdays and that additional hours be provided on Saturday. He noted that some of his constituents have said they have had to wait on the phone for 2½ hours, and that his own staff has tried to get through and had to wait 39 minutes or more.

“Dozens have complained that the call-back feature simply does not work, because they never receive a call back,” Patterson wrote. “Even more frustrating, many constituents have stated that they will wait on hold for long periods, only to be suddenly disconnected either while they are on hold and/or when they finally reach a representative.”

Many of the people dialing EDD call centers have language barriers that prevent them from completing the claims process online or they face technological barriers, including lack of access to the internet, which Vigne says is especially an issue for low-wage workers.

Staffing is one issue that has hampered processing claims both by phone and online.

A federal tax on employers pays for state staffing costs to process claims, and allocations are made based on caseloads. With unemployment at record-low levels in recent years, federal funding to states for administering unemployment has declined by 30% in the last decade, said Maurice Emsellem, director of the Fair Chance Program at the National Employment Law Project in Berkeley.

“It’s basically a boom-or-bust situation,” Emsellem said.

As a result, the number of EDD employees assigned to the field division in which most of the initial claims are processed has declined from 3,067 in 2010 during the Great Recession to 1,516 this year, officials said.

“You’ve got half the staff doing more work,” Hill said.

The EDD has moved to fill some of the gap by bringing in retirees and shifting hundreds of state workers from other jobs to help process new claims and answer phone calls, California Labor Secretary Julie Su said in a videotaped statement Sunday on Facebook.

“I do want to acknowledge the challenges people can have. I know it can be frustrating,” Su said. “We are throwing everything at this right now.”

She said the agency is working hard to get claims processed within three weeks.

The U.S. government standard requires 90% of claims for unemployment benefits to be processed within 21 days, and California was able to stay close to that number in February, according to the most recent reports by the U.S. Department of Labor. In the week ending Feb. 29, the department said California processed 85.7% of first claims within 21 days.

Vigne said more telling will be the performance in March when claims skyrocketed.

State officials would not release newer numbers but said “efficiencies,” including a waiver of some verification until after a check is issued, and the processing of many claims through an automated system, are allowing most claims to be completed within three weeks.

Once the extra $600 from the federal stimulus package runs out, another shortcoming of California’s system will be more apparent: Benefit amounts have not kept up with inflation as they do in other states.

Benefits are paid for with a tax paid by employers on the first $7,000 of an employee’s wages, but California has not increased that taxable amount since 1984, Emsellem said.

As a result, the average weekly benefit in California is only 25% of the $1,340 average weekly wage in the state, so people who lose jobs get only a small portion of their income restored, he said.

Elected officials have been reluctant to raise taxes on employers, so the financial problem has grown.

“It’s gotten a lot worse,” Emsellem said. “The political dynamic is that employers have pushed back on any kind of financial reform.”

The independent Legislative Analyst’s Office said Thursday that officials have the option of boosting benefits to unemployed Californians either through giving everyone the maximum weekly benefit of $450 or by adding $100 per week on top of the federal stimulus payment. Both options would cost about $1 billion a month extra, the office estimates.

Costs could be covered by taking a loan from the federal government. When states don’t have enough money to pay unemployment claims during downturns, the states borrow from the federal unemployment trust fund and the money is paid back in part with a higher tax temporarily placed on employers.

California went through that with the Great Recession, when it had to borrow $10.7 billion from Washington. That loan was only paid back fully in 2018, but in the meantime California had to pay hundreds of millions of dollars of interest on its federal debt.

In 2019, before the pandemic, California collected $5.9 billion in unemployment insurance taxes from employers and issued about $5.5 billion in total benefits.

More borrowing is inevitable not only by California but also by many other states because of the magnitude of the unemployment problem caused by the pandemic, Hill said.

The federal standard is that states should maintain a reserve capable of paying one year of claims during a recession, but Emsellem said that at the end of 2019, California had less than four months of reserves.

“If this drags out much longer, most states are going to end up borrowing from the federal government and it’s not going to be pretty,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.