- Share via

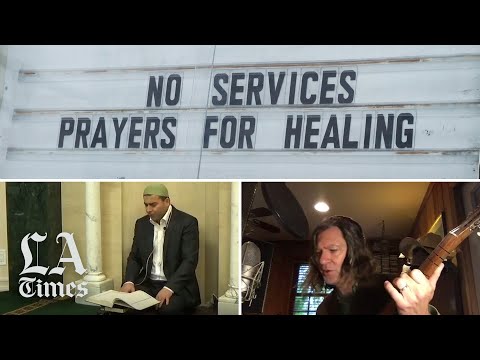

On the morning of the fourth Sunday of Lent, Father Ricardo Viveros felt lost. He sat on the steps of Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Atwater Village and listened to the silence. No cars. No voices.

And for those who arrived, he saw the sadness in their eyes when he told them he could not let them in.

The pandemic had arrived.

Viveros, 40, worried about his congregation in this small working-class community, Forest Lawn to the east, the Los Angeles River to the west. So many of them worked in restaurants; so many were nurses, and he imagined what lay ahead: layoffs, sickness, fear and loneliness.

He stood in his rose-colored vestment.

These are not ordinary times, he thought, remembering the fire that had destroyed his former church almost 10 years ago. As difficult as that was, the community at least took solace in one another’s company.

Now they would have to celebrate Mass without one another, sharing in Scripture, song and a virtual Communion online. In three weeks, the holiest of Sundays — Easter — would be upon them, and Viveros knew they would all have to adapt.

At 10:30, he stepped into the nave and started the procession, his footsteps lost to the echoing strains of piano and hymn. Father Mike Perucho and Deacon Rolando Bautista, friends who would help him, proceeded with cross and Bible.

At the crossing, Viveros genuflected. Stepping around the altar, he turned, initially taken aback by the emptiness. Never had this small church felt so big. Two lay readers sat on either side of the aisle in the first row of pews.

“In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost,” Viveros began, his words captured on Facebook Live.

He hoped his voice did not waver with the emotion he felt inside, and as he spoke the words of liturgy, he began to feel the spirit. Perhaps, he thought, this would work.

Only later would he learn that a few minutes in, the feed froze.

Buffering.

::

On Holy Saturday, just hours before Easter, Viveros has found his place in this new world order.

Working with the church’s IT desk — its de facto webmaster, Silvio Miranda — he has tested and retested the microphones and identified the wi-fi dead zones.

Calla lilies have been placed throughout, and the purple shrouds that covered St. Anthony and the Blessed Mother have been taken down. Tomorrow, he resolved, will be a glorious Easter.

For the last few weeks in isolation, Viveros has tried to keep pace with the needs of his community. Every day he is on the phone, reaching out, talking to 20 members of the church, listening and consoling.

Just a week ago, he made a call to one congregant and heard the words he had dreaded: “Father, you were so meant to call me today because I just found out I have COVID-19.”

Funerals are the hardest, meeting immediate family graveside, everyone wearing masks and standing apart, grieving without the comfort of a Mass.

Teaching is the easiest, children bringing their energy and innocence to the moment, their laughter barely hiding the clank of cereal bowls in the background.

Communion is the loneliest as Viveros intones a prayer for parishioners to repeat, words that only emphasize the distance between the people and their faith.

Since I cannot now receive you sacramentally, come at least spiritually into my heart. As though you have already come, I embrace you and unite myself entirely to you. Never permit me from being separated from you. Amen.

He finds himself spending more time in prayer. In the morning’s early hours, kneeling before the crucified Christ, he surprises himself for how easily he’s laid aside typical preoccupations — scheduling, facilities, finances — his thoughts calm and centered.

“As pastor, I get focused on things that really don’t matter at the end of the day,” he said. “We can be so busy in L.A., all the noise around us. The silence has allowed me to be more with God.”

When Viveros found out that Holy Week had been canceled, he was angry and disappointed with God.

“I don’t do well with the unknown,” he said. “The unknown is disorienting.”

But behind the anger was a feeling of frustration. He didn’t know when the church would open again, and in the parish office stood cardboard boxes of Easter banners he had ordered weeks ago.

They would never be hung.

::

In hardship, communities turn to God.

Viveros had learned this vivid truth on the day before Palm Sunday in 2011, when he stood in the night, hours after midnight, still watching the flames rise over St. John Vianney Church in Hacienda Heights. He had been asleep in the rectory, awakened by pounding on the doors.

St. John Vianney was his second assignment out of seminary school. Having grown up in Harbor City, the son of a construction worker and a hospice nurse, Viveros considers himself fortunate to be able to serve communities in Los Angeles — first St. Genevieve in Panorama City, then St. John.

All but the parish hall was lost during that fire in what investigators determined was arson. A week later, Easter was celebrated in a makeshift space typically used for receptions and Bible study.

He remembers that Mass, the smell of smoke still in the air, the heartbreak and disbelief.

“But at least we were able to hold each other,” he said. “But now we can’t. In its own way, this time it’s more difficult because we have to be apart from one another.”

After nearly four years of celebrating Mass in the tent in the parking lot, the rebuilt church opened, and by then Viveros had moved on, arriving at Holy Trinity in 2014.

::

Viveros applies the lessons of that fire to his ministering today.

“God will use whatever circumstance to make his people stronger if we allow him,” he said. “That community became closer, and through the fire, we became more united.”

But the greater lesson, Viveros believes, is in Scripture.

“This is Easter,” he said. “Jesus has risen. He has gotten out of the tomb, and one day we will get out of the tomb, too, and get back to our normal lives again.”

As he walks through Holy Trinity, he attends to the smallest details, the positioning of flowers, the folding of the altar cloth. He wants the church to be as it has always been on Easter Sunday.

“This is a symbol,” he said. “We will be back to where we should be.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.