Inside teachers’ never-ending crisis shifts: ‘You just keep going all day and all night’

- Share via

It’s just past 8 a.m. at the Inglewood elementary school where sixth-grade teacher Aba Ngissah has taught for seven years.

The blinds on classroom windows, normally open, are drawn, and hundreds of parents and students, rather than rushing for the start of class, are lining up outside the front gate waiting for food.

Ngissah is starting her day in the cafeteria — against a backdrop of giant tissue-paper flowers that are slowly falling apart more than a month after she and her students made them for Read Across America Day. She works quickly alongside other volunteer teachers and Inglewood school district staff, filling hundreds of brown paper bags with boxed cereal, sandwiches, milk, apples and cookies.

It’s been about a month since Hudnall Elementary School shut down, its 400 students among the 6.1 million K-12 California students whose campuses are closed.

After every bag is claimed on this recent Friday, Ngissah will help give out laptops. In the afternoon, she goes home, washes her hands and changes her clothes to protect her elderly mother, who is staying with her. About 1 p.m., she’ll sit down at her computer and begin her real job.

“You just keep going all day and all night,” she says.

That’s just what it means to be a teacher right now.

An unprecedented moment

Nothing — not her classroom experience, her skills as a teachers union organizer nor her work introducing online learning tools — prepared Ngissah for this moment when her classroom would be locked and her students sent home to isolate themselves against the novel coronavirus.

Her first priority is making sure her kids are fed.

At Hudnall, 90% of students come from low-income households and qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, so the safety net of school meals has always been important. Right now, it’s vital.

Coronavirus: While food banks struggle, L.A.’s schools are feeding the hungry

At times, Ngissah and other teachers and staff members use their own money to buy toilet paper, cleaning supplies, ramen noodles, rice and meat for families.

It all happened so abruptly, this radical change to schooling.

When schools closed in mid-March, Ngissah sent books and work packets with lessons to cover two weeks. When it became clear that the closures would continue, she joined others in the district and started distributing laptops along with bags of food.

Then, from her living room, she set up a Google Classroom as it sunk in that she’d have to start teaching her kids via pixels on a screen.

Enduring bonds

Ngissah has been a teacher for more than 20 years, and the main allure to the job has always been the relationships she develops with students and parents.

A UCLA history graduate, she taught her first year at a school in Los Angeles. But when the year ended, she wasn’t sure if she could bear getting to know students again and again only to have them move on.

“I thought, ‘This is too much.’ To me, you get attached and then they leave. It was very emotional,” Ngissah said. With time, she learned that strong bonds endure — former students come back to say hello, invite her to graduations and let her know when their babies are born.

The next year, she took a job at Crozier Middle School in Inglewood, where the paint was coming off the walls and there weren’t enough books for every student.

The district, which is 56% Latino and 40% black, has long struggled financially — in 2012, it was taken over by the state Department of Education, nearly insolvent and in need of millions of dollars in loans to stay afloat. It is currently overseen by a county administrator.

Test scores reflect the depth of its academic challenges. Last year, only 30% of students met or exceeded standards in English language arts, and 18% met or exceeded standards in math.

Low-income L.A. families are struggling to get students connected to the internet even with promises of help from phone and cable providers. A survey found 16% still unconnected.

That first year in her Inglewood classroom, Ngissah found herself looking for books that her students wouldn’t have to share. She uncovered a stash of unclaimed copies of “The Phantom of the Opera” and “A Raisin in the Sun” and had her students read them together and act out the stories.

“My gosh, those students did amazingly well,” she recalls. “I think I fell in love at that point.”

In a classroom, learning can be contagious. That’s what Ngissah loves about teaching — the way students come alive when they make connections between their own lives and her lessons, the way one student’s question can spark a moment of understanding for others, the way she can see students’ faces light up when a point suddenly clicks.

In sixth grade, especially, moments like that can be crucial for kids.

“You can go one way or another,” she says, the students channeled toward success or struggle.

That’s why personal connections are so important. “A student, once they feel that you really care about them and that you really want what’s best for them no matter what, you’re going to push them and they won’t break,” Ngissah says.

A strange new role

When the last person in line receives their food, and the volunteers clean and ready the cafeteria for the next giveaway, Ngissah goes home, changes her clothes and sits down at her couch with her laptop to start teaching.

A couple of weeks into distance learning, about half of her 35 students had not signed on to her Google Classroom, and she had taken on a new role as missing-student sleuth. She started calling homes, talking to parents when they picked up food, asking absent students’ friends to reach out to them.

She began to piece together why they were missing.

Some parents and students didn’t know how to log on. So she would ask parents to put their children on the phone and walk them through, step by step, how to open their email, how to find the dots in the corner of the page that lead to the online classroom, how to enter the code for her class.

“You’re in! You’re in!” she said when she could see on her own computer that they had signed on.

Some students did not want to take a school laptop because they had a family computer at home. She convinced them that one shared computer leaves a student little time to do their work.

Other students lost their passwords, so she reset them. Others needed help getting internet access, and she directed them to the principal, who was coordinating with district officials. Still others spent all of their time on a few online learning games such as Nitro Type — a car racing game meant to improve typing skills — but had not looked at their other assignments.

It took nearly a month, but Ngissah finally reached every parent, and almost all of her students are doing their work. She also knows a few students simply have too much going on in their home lives and can’t make a school a priority.

“It’s not like they don’t want to,” she says. “People are dealing with stuff.”

Coronavirus: Gov. Newsom announced donations and other efforts to provide computers to students during closures, but it falls far short

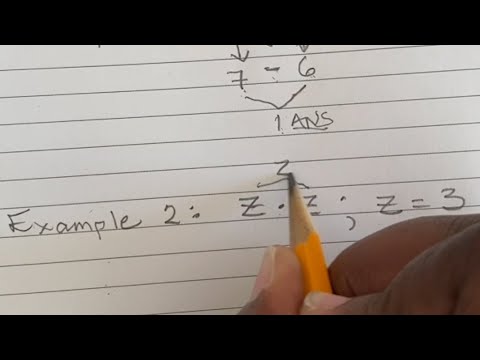

She uses her phone to record herself presenting lessons, such as writing math equations with a pencil on a piece of notebook paper.

“Hello, everyone. I hope you guys are doing well. This is Ms. Ngissah,” she says in the first video. “I’m learning along with you guys, so if I make any mistakes or anything like that, that’s OK.”

As she walked students through how to solve problems, like Z x Z when Z=3, she stopped occasionally to ask questions, as she would in the classroom, to gauge their understanding. Silence. So she started answering her own questions for them.

“Are we substituting Z for 3 or 3 for Z?” she asked. “I hope you all said 3 for Z.”

At one point, the camera image got blurry. She restarted the video. Still blurry.

“I’m doing something wrong,” she said. “I can’t figure it out, though. So hopefully you can see what it’s doing.”

Aba Ngissah, a sixth-grade teacher at Hudnall Elementary School in Inglewood, walks students through how to solve a math problem during one of her teaching sessions from home.

Text and type, the new reality

Ngissah can take questions from students using a chat function in Google Classroom. But it’s nothing like the energy of a physical classroom. Students do their work and ask questions at different hours of the day, sometimes as late as 9 p.m., possibly the only quiet time they have to do schoolwork.

She finds herself responding again and again to the same question because “it’s not like I can say, ‘Go look through this chat and find the answer.’”

When she explained that students would no longer be using the books she sent home with them, confusion reigned in a chain of messages:

“Why did they give us the book at school?”

“What about the book we’re supposed to be doing?”

“Why did we get the book?”

When she forgot to post a quiz and posted a message explaining the mistake, more messages cascaded in: “Where’s the quiz?” “I don’t see the quiz.” “Where are the questions?” Each needed to be individually answered.

“In the classroom,” she says, “students have questions and you’ll answer the question and you can go more in depth and say, ‘Do you understand or do I need to explain it a different way?’”

Now that back-and-forth is time-consuming.

“Texting and typing, what you say and think you’re saying may not be what they’re getting,” she says.

Sandra Lopez, the mother of one of her students, said Ngissah constantly emails her to make sure her daughter is getting her assignments. And when her daughter has questions, she takes her to the food distribution line to talk to a masked Ngissah from a distance.

“She misses school,” Lopez said. “She never thought she would miss school this much.”

As president of the Inglewood teachers union, Ngissah is also fielding calls from educators trying to navigate their new reality.

She’s heard from teachers who want to use online meetings but worry that students may not be safe or comfortable having their peers see their homes or having family members in the background. Many teachers still have missing students, some “radio silent,” Principal Dawnyell Goolsby said.

“Everybody is antsy,” Ngissah says. “They say, ‘I have certain students who still haven’t logged on. I’ve called them, the principal has called them. They keep saying OK, OK, but they’re not logging on.’ You have to ask yourself, is it because there are some families that are dealing with other stuff?”

Ngissah worries about the long-term effect of these months.

“To just have a sudden, ‘Bam you’re done, you’re not coming back to school.’ Just that sudden. And then the fear of watching the news every day and they’re reading it on their phones and hearing more and more people dying. I think we’re going to see the aftereffects of this for many years to come,” she says.

But she tries not to dwell too much on those worries.

Right now, it feels like she’s in a race against the clock to get her students ready for seventh grade. She misses them and is trying to figure out how to replicate the bonds forged in a classroom from afar.

And it’s 9 p.m., and questions are still coming in.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.