Judge refuses to block Newsom’s order closing Orange County beaches

- Share via

An Orange County judge rejected a request Friday from Huntington Beach seeking a temporary restraining order against the governor’s decision to close county beaches in an effort to slow the spread of the coronavirus.

It’s a victory for Gov. Gavin Newsom, who has asserted that it’s too soon to lift the state stay-at-home order. However, the coastal battle in the state is continuing, and an injunction on the governor’s order is still possible.

Orange County Superior Court Judge Nathan Scott set a hearing for May 11 to consider the city’s request for an injunction against Newsom’s order. Dana Point, another Orange County coastal city, had also joined the suit to block the beach closure.

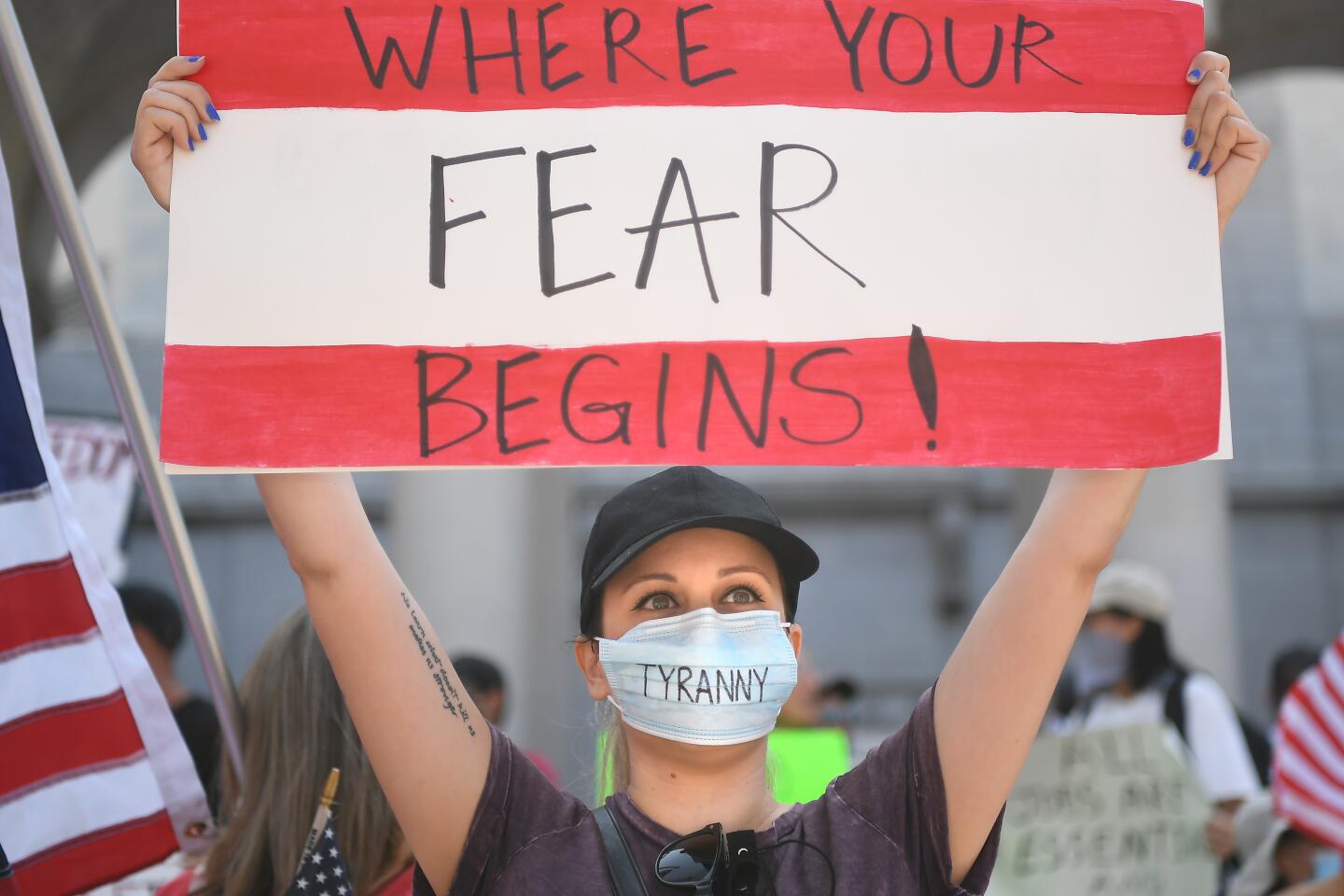

On Friday, hundreds of residents across the state staged protests against the governor’s stance on the matter, saying they were fed up with six weeks of restrictions that have curbed their movements and beach visits.

The crowd that descended on the intersection of Pacific Coast Highway and Main Street in Huntington Beach was significantly larger than a demonstration at the same site near the Huntington Beach Pier two weeks ago. The protesters said they were fighting for their freedom and standing up against what they felt was an abuse of power by the governor.

“I served in the Army and fought tyrants and dictators overseas, and this has gone too far,” said protester Andrew Norman. “I didn’t do that to come back here and live under a tyrant in my own country.”

Around him, children held up signs that read: “I want to go to school. I miss my friends.”

The Orange County beach closure was intended to avert a repeat of last weekend, when thousands flocked to sandy stretches that had been opened, even as shorelines in neighboring Los Angeles County remained closed. L.A. County has reported more than 24,250 cases of coronavirus infection and nearly 1,200 related deaths.

“Specific issues on some of those beaches have raised alarm bells,” Newsom said Thursday. “People that are congregating there, that weren’t practicing physical distancing, that may go back to their community outside of Orange County and may not even know that they contracted the disease, and now they put other people at risk, put our hospital system at risk.”

The governor said the beaches would be reopened soon if the situation in Orange County improves.

But that didn’t satisfy county leaders and officials in some coastal communities, who argue they should decide on shore restrictions based on local conditions.

When Newsom ordered a temporary ‘hard close’ of Orange County beaches, he touched a nerve in a state where a day at the beach is akin to a birthright.

The Huntington Beach City Council voted Thursday night during an emergency session to seek an injunction against Newsom’s order.

Mayor Lyn Semeta said that the beachgoers were maintaining proper distancing over the weekend and that the county has among the lowest per capita COVID-19 death rates in California. Newsom’s order, she said, was prioritizing politics over data. Orange County had reported 2,537 cases of COVID-19 and 50 related deaths as of Friday.

During Friday’s hearing, city attorneys for Dana Point and Huntington Beach said Newsom had issued his order based on a photograph published by a local newspaper instead of relying on data or local law enforcement.

“A hammer was dropped on the city and the city was placed in a very difficult position, literally overnight, to try and deal with this change and direction,” said Huntington Beach City Atty. Michael Gates.

Gates said the city wasn’t aware of the governor’s concern over beach attendance until the order was issued.

“We went to great pains to demonstrate that the pictures [were] taken by a camera at an angle that gives the impression of a very crowded beach,” said Dana Point City Atty. Patrick Muñoz.

Mark Beckington, California’s supervising deputy attorney general, urged the judge to give the state time to assert its authority in briefings before reaching a decision. Beckington said the matter of local control — even for a charter city such as Huntington Beach — wouldn’t overrule the state’s orders, especially amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

Other cities were also weighing their legal options when it came to the beach-closure order.

San Clemente Mayor Pro Tem Laura Ferguson said Thursday that she reached out to the city manager and city attorney Wednesday night after she heard about the proposed order, suggesting they review what legal authority the governor had to close city beaches.

“I’m hoping the governor can cite some valid reason under case law to be doing this to cities because, in my opinion, it appears to be government overreach. Local beaches are under the control of the cities, not the state,” she said.

The Newport Beach City Council planned to hold a special meeting over the weekend to discuss the possibility of challenging the directive.

Asked whether he had any concerns regarding enforcement of the state’s order to close Orange County’s beaches, Newsom said Friday that he has “incredible confidence” in local law enforcement agencies but also stressed that “it’s not just an enforcement mindset, it’s also an encouragement mindset.”

“Again, the only thing — I mean it, the only thing — that’s going to hold us back is a spread of this virus,” Newsom said. “And the only thing that is assured to advance the spread of the virus is thousands of people congregating together, not practicing social distancing or physical distancing. If we can avoid that, then we’re going to get to the other side of this with modifications a lot quicker.”

Six weeks into the governor’s order, pressure has mounted for officials to begin phasing out restrictions. Nineteen counties from Humboldt to Tuolumne have recorded no fatalities from the virus.

Meanwhile, smaller communities across the state that have seen little recorded spread of the virus have been lobbying Newsom to allow them to ease stay-at-home restrictions.

The governor so far has refused, saying conditions are too risky. But one Northern California county appears to be moving ahead anyway.

Modoc County planned to allow all businesses, schools and churches to reopen starting Friday, as long as people stay six feet apart, according to a statement signed by the county health officer, sheriff-coroner, chair of the Board of Supervisors and other county officials.

“The health and safety of Modoc County residents is and continues to be our number one priority. This reopening plan was made in the best interest of residents’ physical, mental and economic health,” the statement said.

The county is one of the least populated in the state, with fewer than 9,000 residents, and one of only four in California that have not reported a single case of coronavirus infection.

It’s unclear whether the reopening will result in a legal showdown between Modoc County and Newsom, whose statewide stay-at-home order supersedes local laws.

Newsom said Thursday that he was aware of Modoc’s announced intentions but did not know details of the county’s plan. However, he said, California’s stay-at-home order “overlays all the orders in the state.”

“You can go further and be more prescriptive and restrictive, but when you loosen up and you loosen beyond … then it’s in conflict, and therein becomes the challenge,” he said.

In Del Norte County, Sheriff Erik Apperson said he would not enforce restrictions on movement at beaches and outdoor recreation areas. The county’s efforts to appeal to the state to open parts of the county, including giving drivers access to state parks, have failed so far.

“This one-size-fits-all response does not serve the people of Del Norte County,” Apperson said. “We are already sacrificing more than our share, and frankly we are exemplary in our efforts as a community. Beaches and outdoor recreation are essential aspects of our daily lives here and critical to our mental/physical well-being.”

California officials still have a lot to do before they can meet the benchmarks that Gov. Gavin Newsom set to reopen the economy and lift restrictions on daily life.

Newsom pointed to examples of other countries that saw a resurgence of the coronavirus after relaxing some of their restrictions.

“Look what happened in Japan. Look what happened in Singapore. Look what happened in China,” he said. “When you pull back too quickly, you literally put people’s lives at risk.”

When it comes to matters of public health, the state has wide powers to enact regulations and restrictions, said Julie Nice, a constitutional law professor at the University of San Francisco.

Counties and other local governments “may enforce health and safety and sanitation rules,” she said, “so long as they do not conflict with the state’s general law.”

That doesn’t seem to be the case with what Modoc County has proposed, she said Friday.

“From everything I can tell from the governor’s orders and what the county has said it plans to do, it appears to directly conflict with state law,” she said. “And I think, as a matter of governmental power, the county’s likely to lose against the state.”

If such a conflict exists, the county could conceivably argue that the state’s rules are unreasonable, but Nice said that would probably be an uphill battle.

“Just thinking logically, a contagious infection does not respect county boundaries,” she said. “And so I would be very surprised if any court would find the state’s statewide rules to be unreasonable, because that’s a very low bar.”

Should Newsom decide to intervene, Nice said, the governor could negotiate directly with county officials to hammer out a resolution or, barring that, the state could turn to the courts to block the reopening plan.

“The general police power of a state, and particularly when it’s applied in the public health context, puts the courts in a position of really being extremely reluctant to second-guess the judgment calls of the scientific experts,” she said.

Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Francisco, San Mateo and Santa Clara counties as well as the city of Berkeley will retain shelter-in-place orders.

Not all local governments are seeking to overturn stay-at-home regulations. Fresno Mayor Lee Brand announced Friday that the city’s local order is now in effect through the end of May — but it has been modified so some businesses can reopen.

In a video message, Brand said Fresno officials will monitor the situation daily and make changes toward reopening the local economy.

“We are still navigating uncharted waters,” he said. “I believe we have a safe and sensible process to rebuild our economy, get back to work and start restoring our normal lives.”

In Los Angeles, Mayor Eric Garcetti urged residents — and protesters — to maintain high standards when following social distancing rules.

“Exercise your constitutional rights. That’s important,” he said. “Whether it’s our beaches, our trails, our workplaces or where we protest, we have to be smart.”

Times staff writer Andrew J. Campa contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.