- Share via

My assignment was to photograph a hospital battling COVID-19, and over weeks of visits, I saw a brave and dedicated staff treat patients with energy and compassion.

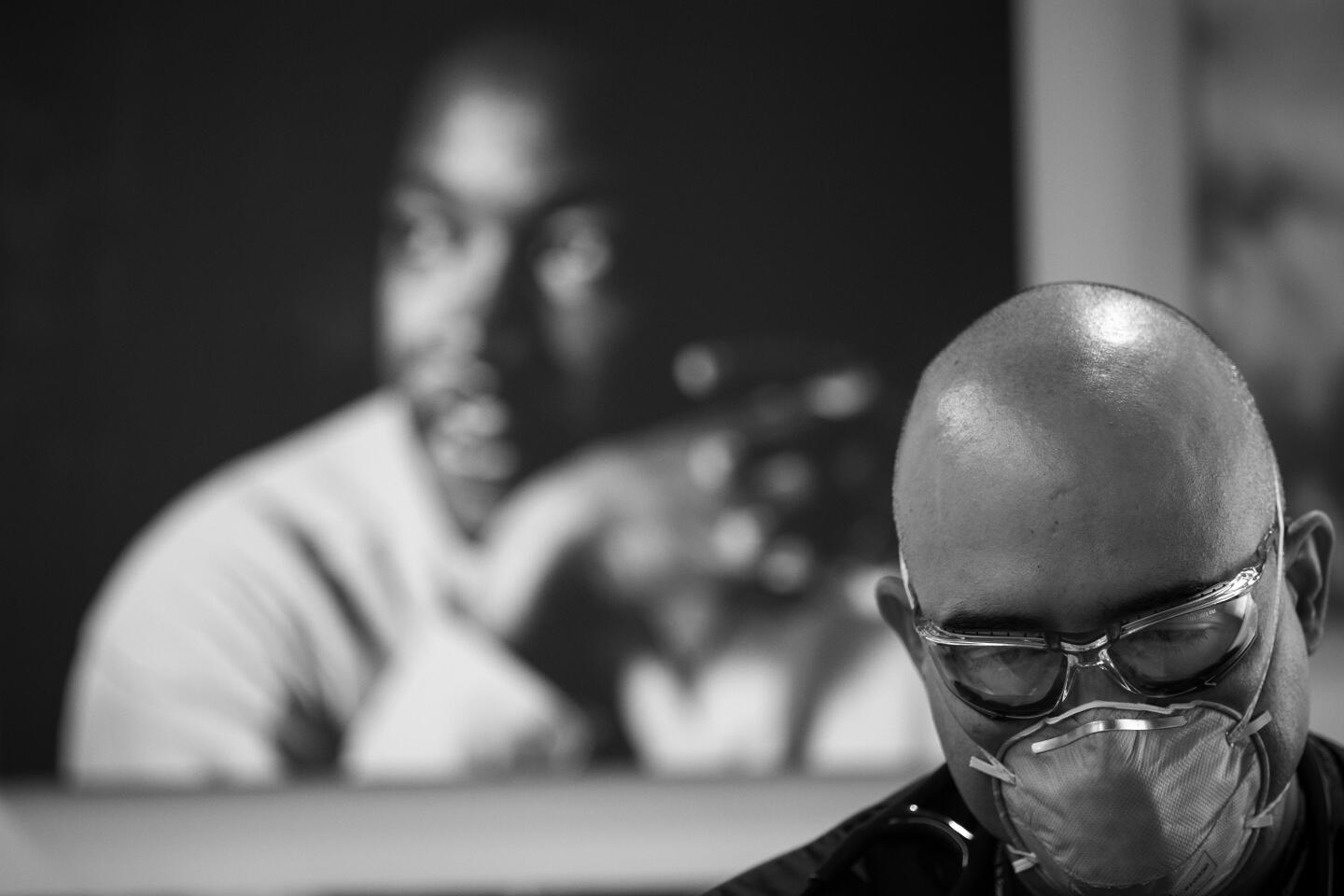

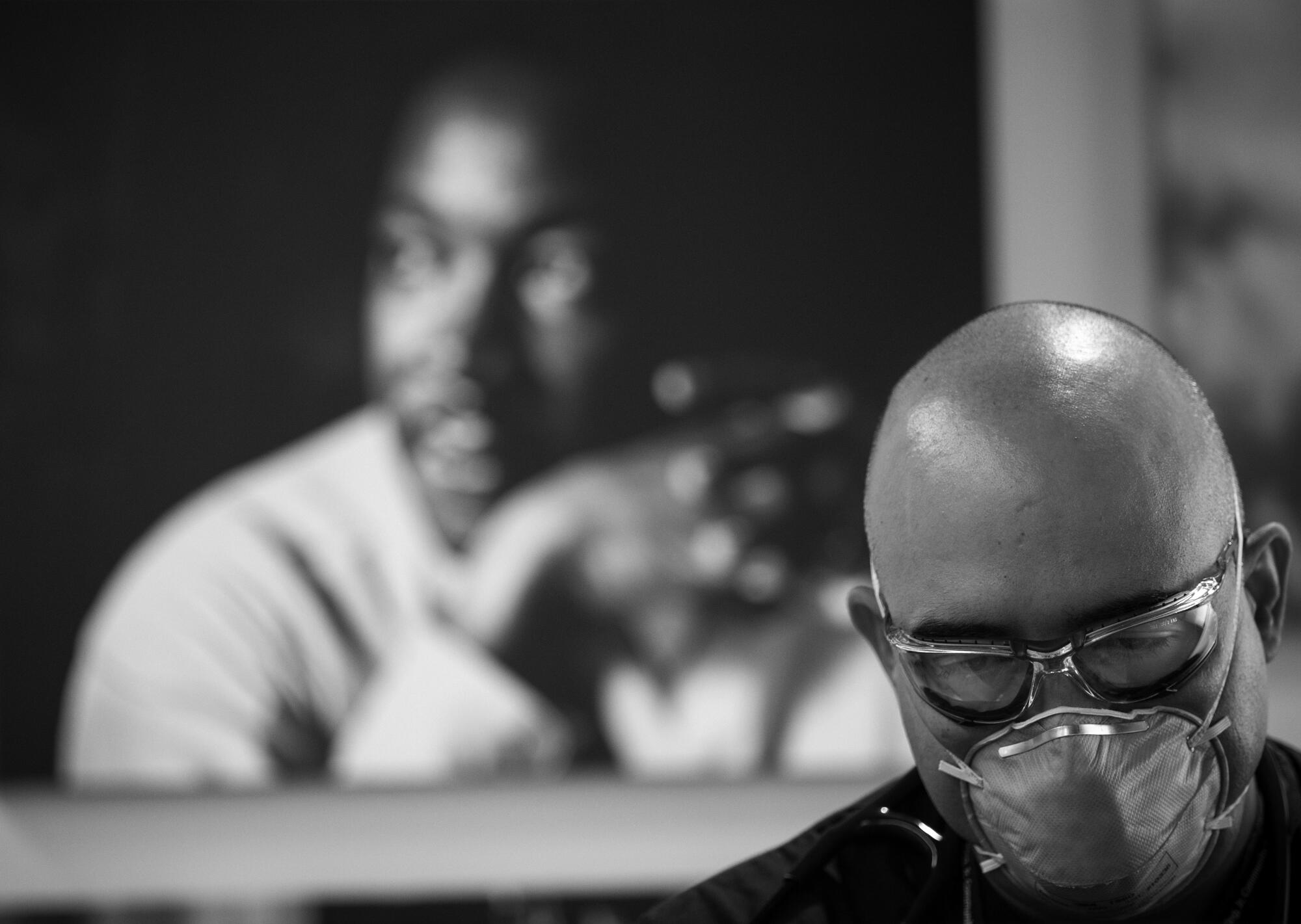

It was impressive but, in a way, not surprising. The staff at Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital has worked to overcome the reputation of the facility’s predecessor, the troubled King/Drew Medical Center, a hospital so bad it lost its accreditation and was nicknamed “Killer King.”

Each day at the new hospital brought scenes of caring and love, of resourcefulness and resilience. Also ever present was the specter of death.

And to my surprise, as I tried to photograph doctors, nurses, technicians and patients, my mind drifted to my college days and a nun I met brimming with energy and compassion.

The hospital staff is saving lives. As I reflect on my days watching that staff, my thoughts pivot from hospital to college and back again, and I realize one might say the same of Sister Marie.

April 15, 3:30 a.m.

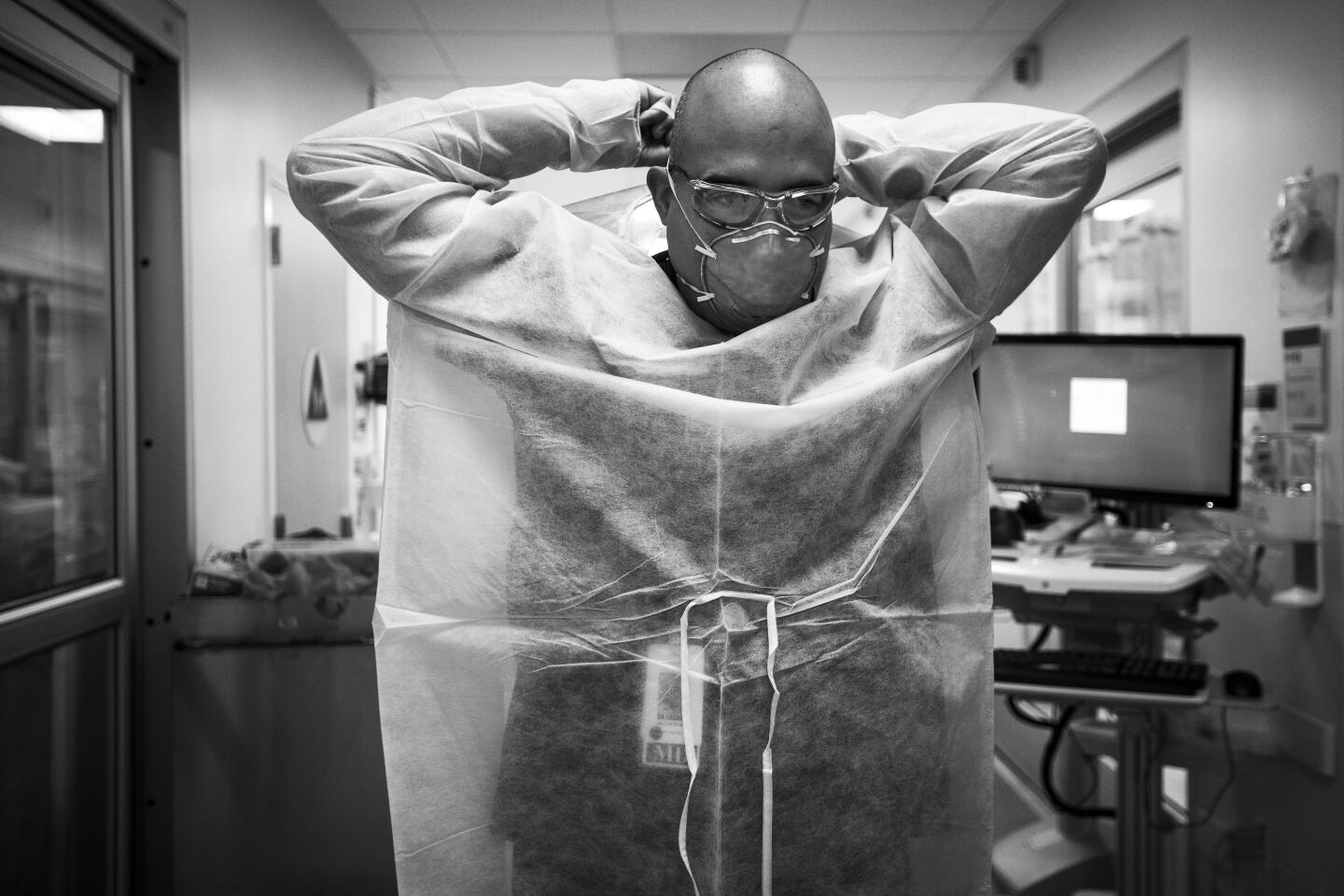

My first day at the hospital won’t start for more than three hours but already I’m awake. I’d been trained on how to don protective gear to guard against the novel coronavirus. I try on my respirator, again.

My primary fear: that I would become ill before I could share this story. The secondary fear: that I won’t truly capture what patients and staff are going through.

In college I’d studied Dante’s “The Divine Comedy” with Sister Marie and this morning I reread a stanza:

O Muses, O lofty genius, aid me now! O mind which inscribed what I saw here your worth will be revealed.

Dante was writing about himself, about his own writing. I return to this poem occasionally when I am about to begin a new project.

7:45 a.m.

Emergency Department

It already feels like a long day, but we’re just 45 minutes into it. I meet up with Dr. Oscar Casillas, director of the emergency department.

Casillas makes his rounds with the vigor and grace of an athlete, which is understandable. He played baseball at USC, first as a pitcher, then as a utility player on the team that won the national championship in 1998.

Casillas often speaks about the shortage of physicians in South Los Angeles and how the health disparities in the surrounding community contribute to the high volume of patients he sees.

The hospital serves a population that’s mostly Latino and young, and those demographics show in its COVID-19 cases. Of 344 such patients, hospital officials say, 84% have been Latino, 12% African American. Four percent were homeless. Average age: 46.

Casillas helped open the new 131-bed hospital in Willowbrook in 2015. When the facility was brand-new, he recalled, patients would reference King/Drew and its troubles. They no longer do that.

The community, he says, and the hospital staff feel they have moved beyond the past, and are facing the pandemic. “There also is a real sense of pride here in accomplishing something that a lot of people didn’t think could happen,” he says.

1981

Kansas

In the fall of my senior year in high school, I visited Saint Mary College in Leavenworth, Kan., for the first time.

In the English department, a white marble sculpture adorned the hallway and one wall featured a painting of Venice. There were tall wooden shelves filled with books.

And there was Sister Marie Brinkman of the Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth. She was the chair of the English department and in charge of the tiny school newspaper, the Taper. She too, I would learn, could see possibilities.

During our first encounter, I confided that I wanted to be on her newspaper staff but couldn’t.

She slyly smiled, as she does, and asked, “Why?”

I told her meekly, “I can’t spell, so I can’t write for your newspaper.”

“That’s what editors are for.”

And in that one sentence, I had a future.

April 18, 10:31 a.m.

Intensive Care Unit

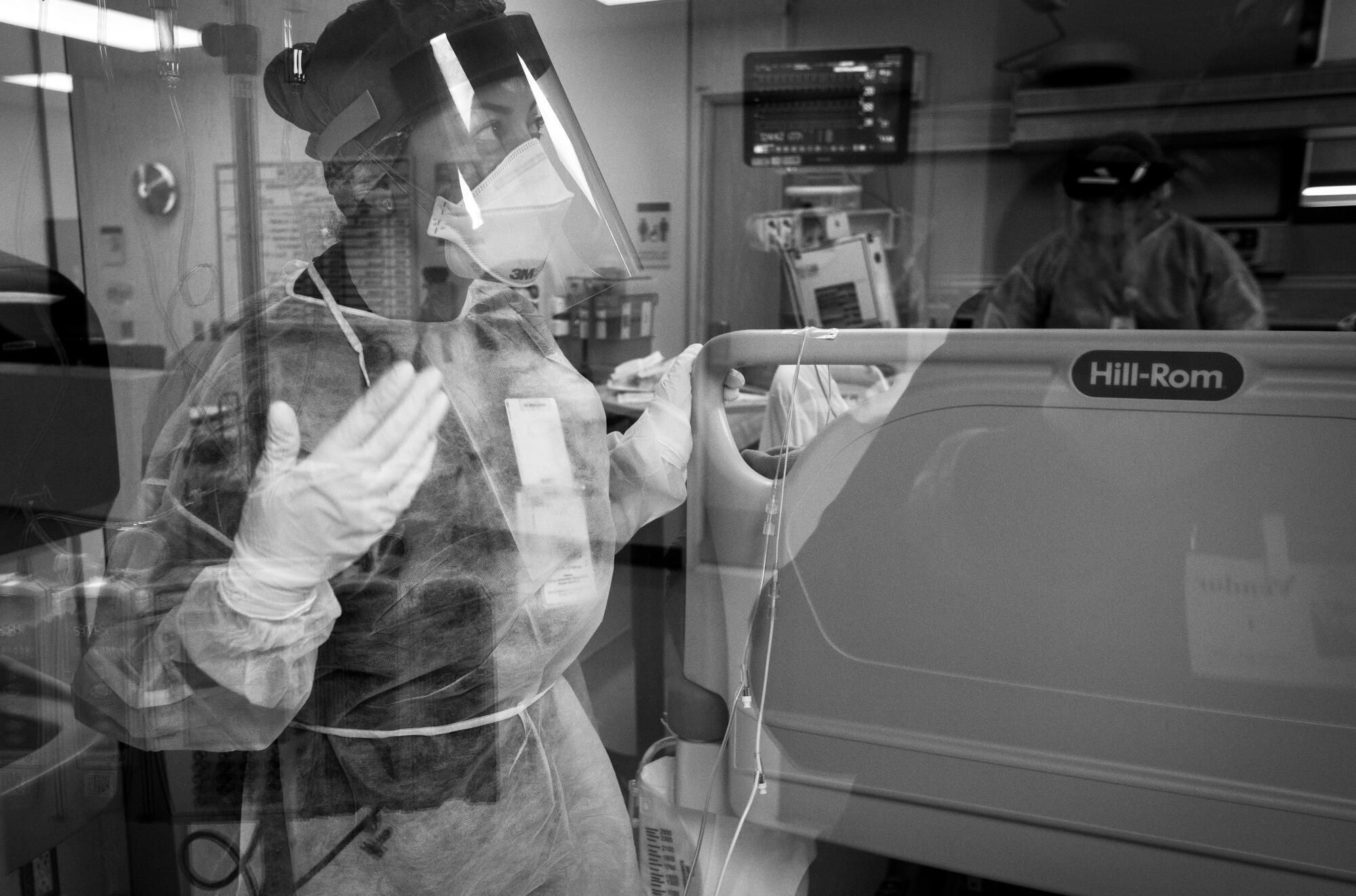

Griselda Llanos, an ICU nurse, never appears to sit down during her 12-hour shift. This morning she has two patients, one with COVID-19.

She spends hours inside the room with him. She changes a diaper, first pulling a curtain to give him privacy. She administers medication. She helps a doctor with a complicated pulmonary procedure.

Before she finally leaves the room, she gently wipes his forehead.

Llanos, 31, has been a nurse more than 10 years. She was raised by a single mother and has a black-and-white tattoo of her mom inside of her left arm.

Her mother was a nurse’s assistant for almost 30 years, but that’s not what drove her to medicine. As a girl, she saw a man fall ill and die at a fast-food restaurant.

“I was maybe 14,” she said. “I felt so helpless because I couldn’t help him. I didn’t know what to do. He was young. I found that pretty traumatizing. Seeing that happen in front of my eyes and me not being able to help pushed me and it led me to nursing.”

Now she must remember to protect herself from the novel coronavirus.

Llanos has to remind herself not to pull off her mask and face shield while in the COVID-19 patient’s room.

1980s

Kansas

I made my choice after meeting Sister Marie and enrolled at Saint Mary College (later renamed University of Saint Mary).

Having me as her student could not have been easy — I was not the best student and never had the courage to tell her I’m dyslexic — but she always had an expectation I would succeed.

She was dedicated to all her students, not just me.

We would sit together for hours inside her lovely corner office, next door to the tiny newsroom where I wrote and photographed for the Taper. The office featured a large, tan IBM electric typewriter, always humming, and a black-and-white photo of her predecessor as chair, Sister Mary Ernestine, with a pet parakeet named Mr. Blue.

We would pore over my seminar papers, simple newspaper articles and essays on Dante. She would emphasize her point by blinking both eyes hard, behind her thick glasses.

Sometimes we would walk around campus and end up in a kitchen, where she would make me toast and we would sit and talk some more. There was always a historical context to our conversations. We talked about our families, movies, history and travel, but also justice, ethics and the nature of suffering.

April 23, 8:23 a.m.

COVID-19 Unit

Dr. Maita Kuvhenguhwa, an infectious-disease specialist, is chatting warmly in Spanish with Maria Cuellar, holding Cuellar’s right hand in her two gloved hands. COVID-19 disproportionately harms Latinos and African Americans, but Cuellar, 63, will be going home soon.

Dr. K, as many call her, feels a unique connection to the hospital. Her father, Dr. Amos Kuvhenguhwa, had practiced at King/Drew. Born in a small village in Zimbabwe, he decided at a young age to become a doctor because his mother nearly died giving birth to him.

Kuvhenguhwa would go to King/Drew with her father and, as young as 4, would sit at the nurse’s station. Sometimes his patients wanted to meet her. “It always struck me that his patients were so grateful,” she says.

He was a trauma surgeon and Kuvhenguhwa sometimes saw him in news reports.

He saved lives.

“I didn’t really recognize how powerful that was until I got older,” she says.

One sad fact about King/Drew’s demise was that the hospital was created to address some of the wrongs that triggered the Watts riots of 1965.

As King himself explained: “These riots grew out of many things, particularly the explosion of accumulated frustration that had been developing across the years, as a result of the long night of poverty and economic insecurity.”

Now, one reason why Dr. K works here is because her father had wanted to practice at King/Drew’s successor. But he died in 2014, a year before the facility opened.

Of the hospital and its role in the pandemic, she says: “The neighborhood is resilient. The hospital is resilient, and we will get through this. … We have to keep pushing through. This is just one more obstacle in our path, and it’s not going to break us.”

1995

Los Angeles

On my 31st birthday, Sister Marie was in Santa Monica working on a book, “Emerging Frontiers,” a history recalling the turbulent times and renewal of her religious community.

I borrowed my cousin’s vintage red Mustang convertible, and we giggled as I drove us around Westwood with the top down.

Sister Marie had become a constant friend, a constant listener. Years later I asked her to pray for my parents when, one by one, they became ill. She attended my mother’s funeral and called the day my father died. I still have her voicemail.

She understood loss. She, too, had lost her parents as well as three brothers.

And, as I had, she had attended Saint Mary College, graduating in 1948. In her 38 years in the English department, and in retirement, she savored interacting with staffers and students, attended parties and baptisms, weddings and funerals. She delights in the presence of children.

She became a nun in 1950, taking vows of poverty, chastity and obedience.

When I asked about the obedience vow, which suggests unthinking compliance, she replied that it was an obligation to inform her conscience to the best of her ability — and then to follow her conscience. As usual, her interpretation was deeper and more nuanced than mine.

A few years ago, I took her to dinner to thank her for being my professor and my friend. We followed up the next day with a trip to the drug store. Who knew shopping could be so much fun? She wanted dark chocolate, soap and a pair of short stockings. I would have taken her anywhere.

May 4, 3:38 p.m.

COVID-19 Unit

While working in the COVID-19 unit on the fifth floor, I receive a text:

Sr. Marie has chosen to accept hospice care.

She has been battling Parkinson’s disease for years. On this day, she is just a few weeks shy of her 94th birthday. As I try to absorb the news, it’s hard to breathe because of my half face mask with two pink P100 filters.

But now I must focus on Quinnece Washington, who followed in her mother’s footsteps into nursing. At 31, she is starting her career in the COVID-19 unit. She admits to feeling scared at first.

“Who would have thought as a new nurse you would be a front-liner on a huge pandemic?” she asks. “I know I will have a story to tell to my kids. About being brave. When something arises, you just kind of just go at it.”

She and her husband, a respiratory therapist, have two children and they look after her 85-year-old grandmother.

“Sometimes, when I am in the [patient’s] room, I am praying, ‘Please, God, shield me.’ I want to provide good quality care and be there for a patient. I also want to protect myself too. I ask for the strength to really get me through this.”

Like the rest of the COVID-19 crew, she repeatedly washes her hands and carefully dons and doffs her protective gear. Her shifts last 12 hours.

“Imagine as a patient being in the hospital with no family around, no friends. You don’t have the interaction with the care team because you have to limit the exposure.”

Yes, I can imagine.

Over the years, Parkinson’s robbed Sister Marie of the ability to write, and I once asked her if she was suffering.

Sharp as ever, she assured me, “Absolutely not.”

She made it clear there is distinction between suffering and struggling. She was struggling.

May 17, 11:02 a.m.

Intensive Care Unit

Hearing families cry over an iPad while their loved one is in ICU is painful, and I witness it again and again as nurses raise up the devices so family members can see one another.

This morning, I take a break from photographing to call Kansas.

Her nurse holds up the phone for Sister Marie and me.

Recently she had told me, “We are going to have great adventures together.” This time she asks me to visit and I try to explain I can’t because of the virus.

She sounds tired but like herself.

I just want to sit with her and tell her all about the people at Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital, people she surely would admire.

I want to tell her about Dr. K — how her first name, Maita, means “thank you” in her father’s native language, and how she is looking to a future beyond COVID-19.

I want to tell her Dr. Casillas played catch in the park with his children after his shift ended. They wore masks, but they played. I want to tell her about the nurses, like the seasoned Llanos and the newcomer Washington.

But I can’t do that now. Like the grieving families here, I will say my goodbyes from a distance. I hope the hospital staff and their patients know none of us is truly alone in our suffering.

We have one another.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.