L.A.’s Black community is happy to have new white support — but it’s long overdue

- Share via

As Donny Joubert watched a Minneapolis police officer kneel into the neck of George Floyd, he was outraged at yet another example of police brutality.

So too was the rest of the nation, and the pain of Floyd’s death has resulted in weeks of mass protests.

Joubert and others in the Black community are encouraged that these protests are centered not in South Los Angeles but in upscale business districts and locales and have attracted a kaleidoscope of races demanding justice. But they’re asking a simple question: Where have you been? Because this is long overdue.

Black folks remember the hope and disappointment following the Watts riots in 1965 and the Rodney King riots in 1992, when the nation’s attention eventually turned away from racial injustice.

The show of unity now is fine, but what happens when the passion of the protests cools down? Will the thousands demonstrating on the streets move on?

Longtime community activist Earl Ofari Hutchinson, president of the Los Angeles Urban Policy Roundtable, said unless this infusion of energy from white people, young activists and others translates into continued mass action, education of Black issues and action at the voting booth, the weeks of protests may not move the needle toward lasting change.

“I’m cautiously optimistic that this will be more than just a momentary, thrill-seeking high for many, and that many will continue to be moved by the power of advocacy for racial justice, that they will continue to be engaged,” said Hutchinson, 72. “There has to be organizations that spring forth in addition to Black Lives Matter with doable, practical programs that can engage them.”

Joubert hopes so, too, because he has seen the destruction of civil unrest firsthand.

He remembers as a 5-year-old comparing his toy soldiers to real-life National Guard troops as they patrolled the streets during the Watts riots. Twenty-seven years later, he and other gang members brokered an unprecedented truce between rival groups during the King riots, an often overshadowed gesture amid the more than 60 lives lost and $1 billion worth of property damage in the city.

In both instances, white people were largely oblivious to the inequities of Black citizens. They shouldn’t have been, he said.

“We all have to live together, and it took this long for folks to realize what we have been going through,” Joubert said. “Rodney King should have been a highlight. The riots in 1965 should have been a highlight. We’re taking a big step forward, but Floyd shouldn’t have had to lose his life for this to happen.”

This time, policy changes have followed swiftly, including some cities banning police chokeholds and initiating serious discussions to redirect funding from police budgets to improve housing, healthcare, education, mental health services and other resources.

Los Angeles is no stranger to public uproars sparked by racial tension. But none of it looked like it does now, with tens of thousands of people of mixed races descending on Hollywood Boulevard on successive weekends for peaceful protests.

Sporadic thefts and vandalism followed nonviolent protests over Floyd’s death in Santa Monica, Beverly Hills and the Fairfax district but did not match the destruction that sprawled across the city in 1992 after a jury acquitted the four officers who were videotaped beating King, a Black motorist, after a high-speed chase. Plots of land in South L.A. where buildings once stood remain empty.

In 1965, 34 people died over six days of unrest after a scuffle broke out in a crowd when a white California Highway Patrol officer pulled over a Black motorist in Watts.

In both instances, critics say, substantial reforms didn’t happen. Agencies wrote detailed reports. Task forces were created. Promises were made.

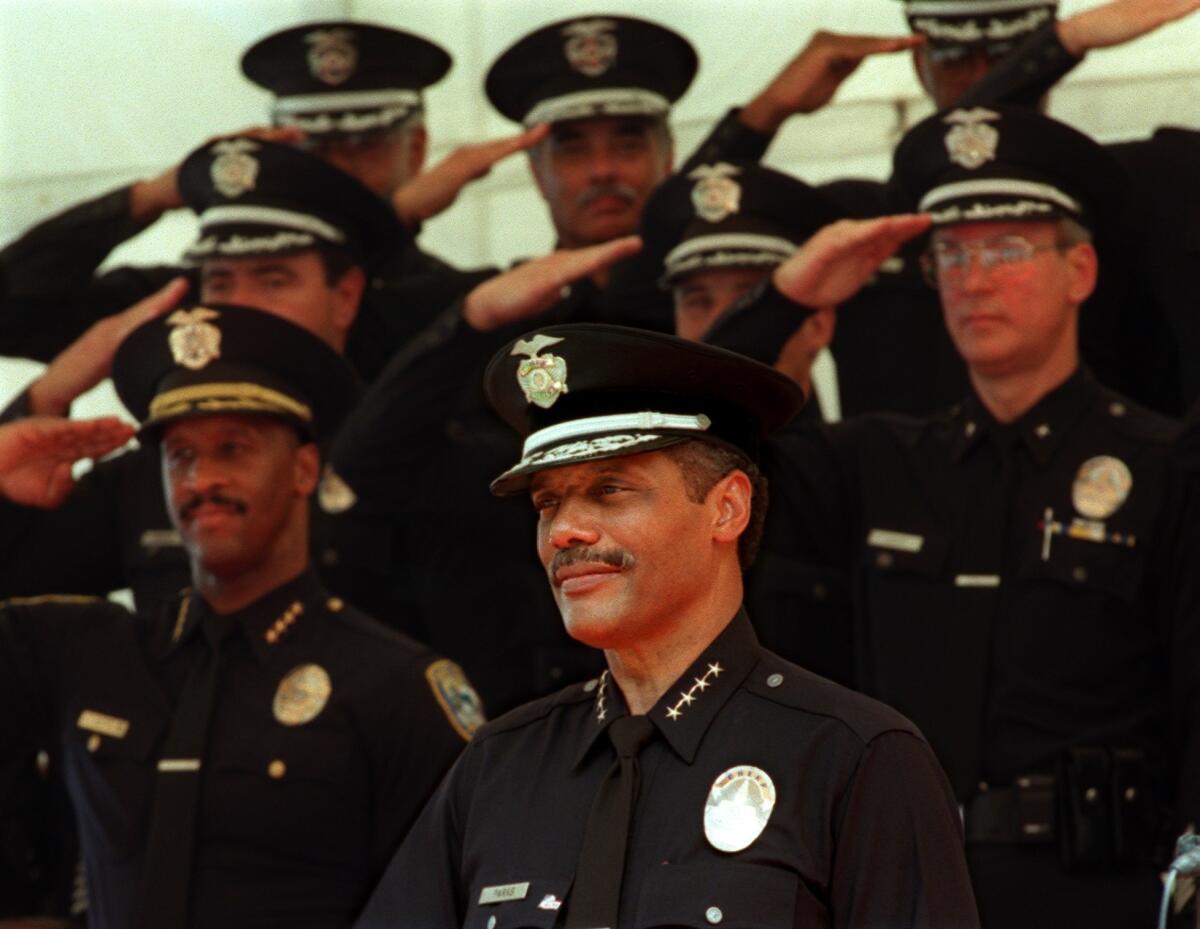

Watts, the 1992 uprising and now the protests over Floyd’s killing came from years of festering frustration toward the inequality Black Americans suffer, said Bernard Parks, one of the few Black Los Angeles Police Department officers in 1965 and a deputy chief during the King riots.

“When they do the study for finding out why people went out of their houses and into the streets in 2020, they’ll probably see the identical issues,” said Parks, 76, who later became chief of the department and a City Council member. “None of that has changed over all these decades. Investment in community, economic imbalance, education — none of that has been resolved.”

Watts still suffers from a high poverty rate, ranking as the 13th-worst neighborhood in Los Angeles for violent crime per capita, according to a Times analysis of crime reports. The area has seen progress, including a $35-million federal grant awarded in April by the Department of Housing and Urban Development and a community policing relationship that activists, politicians and the LAPD say is strong. But it still bears the scars of its past.

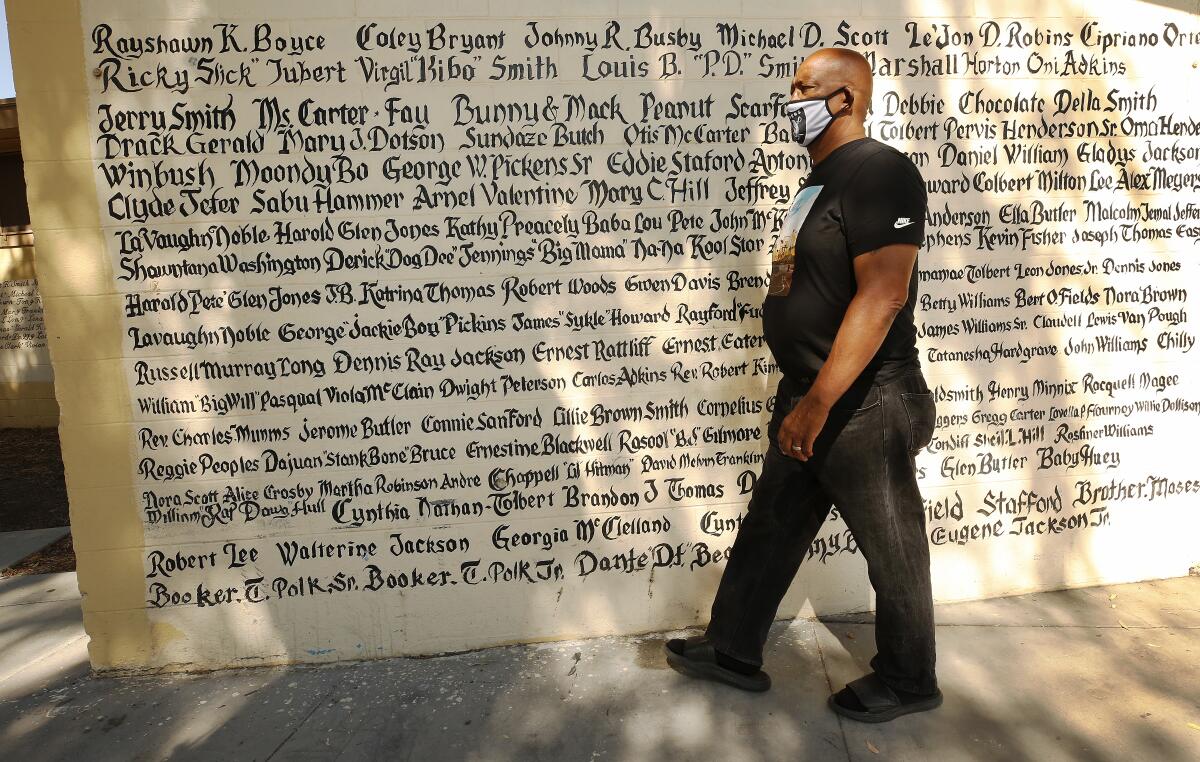

On a recent afternoon, Joubert walked into the Boys & Girls Club at Nickerson Gardens, the low-income public housing complex where he was raised, to sort canned food for families in the area. Outside the gym is a mural with names of people dead from gang violence or other causes. To the community, it’s a sacred monument — even children know not to mess with it, he said.

Joubert helped to open a boxing academy at the gym last winter to keep kids active and out of trouble. But the COVID-19 pandemic — which has killed Black people at a disproportionate rate — forced a temporarily closure. He now hands out food to families every Friday with help from the Gang Reduction and Youth Development Foundation.

When he first heard of Floyd’s death and saw the anger that initially spurred some vandalism in Los Angeles and other cities, he and other gang interventionists reached out to young people and counseled them. It was OK to be mad, they said. But they encouraged them to take that anger out productively in peaceful protests; they shouldn’t destroy property, especially in their neighborhoods.

“We’re not new to this,” Joubert said. “We’ve already been through two of them. There’s nothing else left to burn.”

As he watched television, he was shocked as more and more white people joined the marches. It almost brought a tear to his eye, he said.

Those scenes surprised others.

“I never thought I’d see the day they would do any of this in Beverly Hills,” said William Taylor, with a chuckle.

Taylor, 72, sat in a chair at Tolliver’s Barber Shop in South Los Angeles, looking at a well-known 1992 photo of a laundromat engulfed in flames, one of the many reminders of the mayhem. He’s still upset that some vacant land around the community hasn’t been redeveloped.

The day after the King verdict, Taylor, who was then the owner-manager of his father’s furniture-moving business, was scheduled to do a job. Because of the danger, he called his client, a white woman, asking if he could reschedule. She refused.

“Her attitude was, ‘They are not rioting where I am located, so I still want service,’” Taylor said.

The journey to her Hollywood apartment was “painful,” he said. He bypassed Normandie and Vermont avenues, routes that would have made the drive shorter but were inaccessible because rioters were pulling people out of their vehicles and beating them. When he arrived, he said, the woman had become fearful as the devastation crept closer to her area.

He said today’s movement may have more impact because, unlike his client then, white people have not waited to show concern until their own lives were affected. But he also hopes those who are just now joining the cause develop a deeper understanding of the systemic inequities that underpin the protests.

“If I were younger, I would be out there walking with them,” Taylor said. “I dream of a better world, and I know myself and others would gladly help them understand what we’ve gone through and be a sounding board.”

Ann Tolliver Binion, 78, whose brother owns Tolliver’s Barber Shop, said the current movement reminds her of a biblical story in which God forced the prophet Moses and his followers to wander the desert for 40 years. The Israelites could enter the Promised Land only after the older, more stubborn generation died off, and Binion thinks that is similar to what’s happening now.

“A lot of this stuff has been ingrained for so long that the older generations may not have been able to comprehend,” Binion said. “I think things will change because this generation understands. And no matter who you are, how can you watch that George Floyd video and not demand change?”

Parks, too, is encouraged. He said during both previous riots he overheard insensitive comments from white colleagues in the department who openly supported King’s beating. Some questioned why they were responding to riots in Watts.

“Some officers were asking, ‘Why are we concerned with that part of the city?’ and a lot of Black officers had to challenge them and say, ‘We care because my family lives in South Los Angeles,’” Parks said.

The deliberate decision of protest organizers to steer demonstrations to whiter, wealthier areas may have played a role in a wider awakening, said Jody Armour, a professor at the USC Gould School of Law who specializes in racial issues.

The fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin in 2012 highlighted racial profiling, but since then, the accumulating instances of killings caught on video — Ahmaud Arbery, Eric Garner and others — have also shocked people’s senses.

“We’ve seen for so long that the cost of injustice has been limited to certain communities and geographic areas,” Armour said. “Now, with these marches, we are seeing more privileged communities start to bear that price. For us to make real progress, we all collectively have to say that the price of injustice is greater than the cost of justice.”

As Joubert took a break from lifting plastic containers with canned food in the gym, he reflected on what is the next step for creating real change: voting — knowing the issues and then acting on them. He’s glad to have new allies on board, even if they came late, he said.

“We have to live in the here and now,” Joubert said. “We have them now waking up to what has been happening to us for a long time, and we have to seize this moment. We can’t let it go to waste.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.