Los Angeles cuts LAPD spending, taking police staffing to its lowest level in 12 years

- Share via

The Los Angeles City Council voted Wednesday to cut hiring at the Police Department, pushing the number of sworn officers well below 10,000 and abandoning a budget priority once seen as untouchable by city leaders.

Faced with a grim budget outlook and deluged by demands for reductions in police spending, the council voted 12 to 2 to take the Los Angeles Police Department down to 9,757 officers by next summer — a level of staffing not seen in the city since 2008.

Overall, the council’s decision delivered a $150-million hit to the LAPD budget, much of it coming from funds earmarked for police overtime pay. Councilman Curren Price, who pushed for the cuts, said two-thirds of the savings would ultimately be funneled into services for Black, Latino and disenfranchised communities, such as hiring programs and summer youth jobs.

“This is a step forward, supporting minority communities in ways in which they deserve — with respect, dignity and an even playing field,” said Price, the only Black member on the council’s budget committee.

Councilmen Joe Buscaino and John Lee cast the two opposing votes. Buscaino said afterward that the city should have approved more money for a community policing program, not “a reactive, feel-good budget cut.”

Wednesday’s actions showed just how much spending policies and views on public safety have shifted at City Hall following mass protests over police brutality. As recently as April, Mayor Eric Garcetti had been pushing for a 7% increase to the LAPD budget, a move he no longer favors.

Reaching and maintaining a 10,000-officer force had been a longtime priority for city leaders. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa celebrated in 2013 when the LAPD reached that number for the first time. That year, while running for mayor, Garcetti vowed to preserve that staffing level.

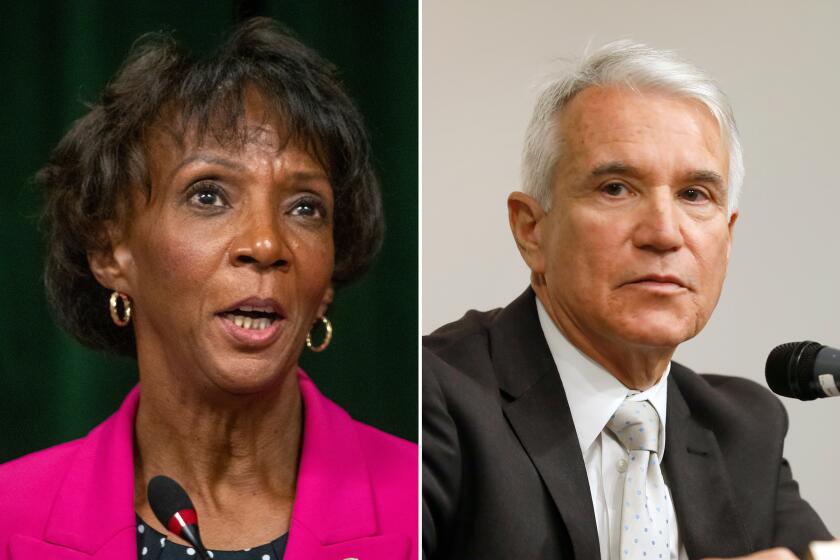

Protests over police brutality and criminal justice reform intensify race for L.A. district attorney

The battle between Jackie Lacey and George Gascón to lead the nation’s largest local district attorney’s office is already being influenced by the fallout of national calls to change American policing.

The LAPD currently has a sworn deployment of roughly 10,000 officers, according to a recent report by city budget analysts.

The council’s decision on Wednesday will allow the LAPD to hire only half the number of officers needed to replace those who resign or retire in the coming year.

The $150-million cut to the LAPD fell far short of demands from Black Lives Matter-Los Angeles and its allies, who had pushed for a “People’s Budget” that would effectively eliminate police spending and redirect the savings to housing, mental health services and other needs.

“That is literally pocket change,” said Rebecca Kessler, a resident of Van Nuys who called in to the council this week. “It’s a slap in the face. You need to defund the police, take way more money, put way more money into these programs.”

LAPD spokesman Josh Rubenstein said Wednesday that the department is still reviewing the impact of the approved cuts.

The city spends roughly $3 billion annually on the LAPD, once pensions and other expenses are included. In recent months, progressive activists have called on city leaders to slash that funding and redirect the proceeds to other needs, demanding cuts ranging from 90% to outright abolition of the LAPD.

In response, council members have begun exploring ways of diverting many calls for help — those that involve nonviolent incidents — away from the LAPD and to other city workers. Council members voted this week to direct city staffers to come up with an “unarmed model of crisis response” for further review.

Melina Abdullah, co-founder of Black Lives Matter-Los Angeles praised that step. “Rolling back police functions has the potential to have a far greater impact on advancing the call to defund the police than approving a meager cut of $150 million,” she said.

Others questioned whether the LAPD cuts would harm neighborhoods.

Ray Rios, president of the Hillside Village Property Owners Assn. in El Sereno, said his community has been experiencing a spate of car break-ins and illegal fireworks. City leaders should address demands for change at the LAPD by focusing on reforms, not reducing the size of the force, he said.

“Without any enforcement, [crime] is going to get worse,” Rios said. “The big question is, who’s going to keep order?”

While activists repeatedly delivered the message “defund the police,” council members focused much of their deliberations on the city’s financial woes. Tax revenues have fallen dramatically below projections since the coronavirus outbreak and the shutdown of an array of businesses.

The city’s budget analysts have repeatedly warned that the city could find itself short by $45 million to $409 million. And in recent days they began sounding new alarms about the resurgence in coronavirus cases across Los Angeles County, and what that could mean for city finances.

On Tuesday, council members quickly passed a plan for pushing as many as 2,850 civilian city employees into retirement, by offering them buyout packages of up to $80,000. Employees may begin applying for those payments next week.

If everyone eligible for the retirement program takes part, the city would save $58.7 million this year and an additional $125 million in 2021-22, said City Administrative Officer Rich Llewellyn, the high-level budget analyst.

Both the LAPD cuts and the employee retirement initiative were also billed as ways to delay another budget-cutting measure: putting nearly 16,000 city workers on furloughs. The furloughs, which were proposed by Garcetti but opposed by city employee unions, would have forced civilian city workers to take one out of every 10 days off, cutting salaries by 10%.

Some of this week’s decisions by the council could saddle the city with hefty costs in the future.

Of the $150 million in cuts to the LAPD, about $97 million would come from cuts to overtime pay for police officers. Council members and the city’s policy analysts cautioned that at least a portion of those overtime hours could still end up being worked by the LAPD, particularly if the city experiences a major emergency.

Attorneys for Los Angeles on Tuesday argued against a temporary restraining order to block police from using batons and tactical bullets to control crowds.

In those instances, the LAPD could “bank” that overtime, letting officers work the extra hours but delaying payment until a future year, allowing officers to be paid for those hours at higher salaries.

The plan to cut the civilian city workforce could also come with a delayed cost. If every eligible employee takes part in the program, the city will need to spend $28.5 million on buyout packages this year — $10,000 per worker, according to Llewellyn, the budget analyst.

The city would need to spend an additional $128.5 million on those payments the following year, he said.

Llewellyn called the program a “financial winner for the city,” but also acknowledged that the mass departure of thousands of city workers would result in a reduction in taxpayer services. To achieve major savings, he said, the city should replace only a small fraction of the positions that become vacant.

“Most of these choices are not choices that any of us would have made in a normal circumstance,” said Councilman Paul Krekorian, who heads the budget committee. “But we’re not living in a normal circumstance.”

Krekorian also said $40 million of the money cut from the LAPD budget will be set aside as an “insurance policy” to help pay for city services if the retirement program does not generate enough savings. Another $90 million will go into a reserve account titled Preservation of City Services, Reinvestment in Disadvantaged Communities and Communities of Color and Reimagining Public Safety Service Delivery.

Craig Lally, president of the Los Angeles Police Protective League, the union that represents LAPD officers, described that account as a “slush fund.” He warned that the planned reduction in police officers would result in slower response times.

Over the next 12 months, officers who do end up working overtime won’t be paid until years into the future, and at more expensive rates, Lally said.

“They passed a budget by putting everything on the city credit card,” he added.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.