As protests against police brutality go global, these Latina moms fight in memory of their sons

- Share via

Rosa Moreno had heard many stories in her neighborhood about mothers whose sons were killed by police.

Their pain seemed unspeakable. Their cases left a trail of questions.

“Police are supposed to keep us safe,” Moreno used to think. “Why would they hurt people and take away their children?”

Then, in 2017, her 23-year-old son, Cesar Rodriguez, died brutally in an encounter with law enforcement, and the mother of three became yet another cautionary tale around East L.A.

In recent years, she and other women from Lincoln Heights, Boyle Heights and East L.A. who have lost their sons to police violence have found solace and a sense of collective voice in one another. Their group numbered less than a handful when they began about three years ago, then gradually, as law enforcement shootings continued, grew to 15.

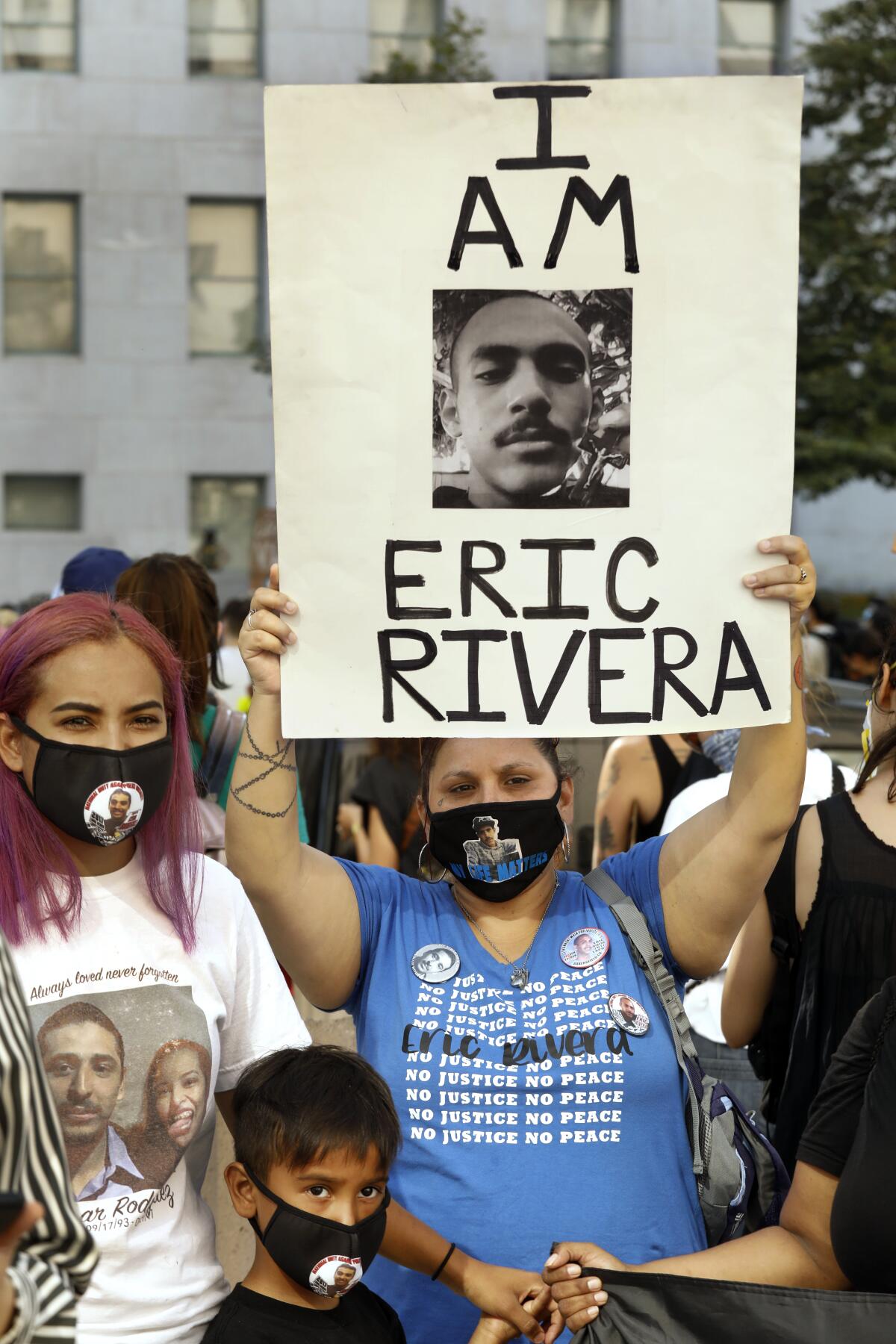

As protests against police brutality have spread nationwide and the rallying cry “Black lives matter” has gone global, these Eastside moms have pushed for change, largely on their own. They comfort one another while also pressuring law enforcement to overhaul its use-of-force policies and better its relationship with the Latino community.

“We have no phrase, not even a name,” said Moreno, 51. “But we’re warriors for our sons. We support one another like family.”

Some of them found each other at their most desperate moment, on the side of road, in parking lots and housing complexes roped off by yellow crime tape, just hours after their sons were killed. Others connected in support groups.

At one such group about a year ago, 10 mothers were brought together to talk about the effects of gang violence in East L.A. But when it came time to speak, the women shifted to law enforcement brutality.

“It turned out that about 8 out of 10 of the women had had a child killed by police,” said Johnny Torres, an organizer with Soledad Enrichment Action, a gang intervention program paid by L.A. County.

Since Torres began serving the area in late 2017, he’s spent a lot of time getting to know the mothers. And though his mandate in East L.A. is gang intervention, there’s been so much concern about the violent behavior of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department that Torres has become one of the few people the community turns to for help. His phone rings at random hours with desperate calls from mothers, siblings, aunts and uncles searching for a loved one who they fear may have faced off with deputies.

Department officials seldom release information on shootings and fatalities, Torres said, so he and the families are left to piece together fragments. He often rushes to crime scenes to be sure their legal rights are being respected.

“A lot of times, there’s no remorse, no compassion, even if the guy deserved it,” Torres said about deputies. “They need to at least respect the family’s pain.”

In the last three years, his list of those killed by law enforcement on the Eastside has grown: Jose Serrano, 23; Omar Garcia; unnamed victim, 20; Paul Rea, 19; Ivan Pena, 42; Fernando Cruz, 18; Rene Herrera, 40; Anthony Vargas, 21; Jesse Romero, 14; Jose Mendez, 16; Christian Escobedo, 22; Edwin Rodriguez, 24.

Some reportedly died as they tried to run from authorities. Others allegedly engaged in a physical struggle, carried a weapon and, in some cases, reportedly shot at law enforcement.

Nearly all the victims died in East L.A., an unincorporated area of L.A. County that’s 96% Latino. The region is under the sheriff’s jurisdiction. While in nearby neighborhoods the Los Angeles Police Department has been scrutinized for its use of force, including over the last few months, the Sheriff’s Department has its own long history of violence and abuse, feeding the community’s wariness. Some of the mothers have said they and their families have been harassed by deputies after their sons were killed.

Officials with the Sheriff’s Department did not respond to requests by The Times seeking comment. The Times this week filed a lawsuit against L.A. County, alleging that the department has repeatedly refused to turn over public records, including those about deputies involved in misconduct or shootings.

Figures tracking fatal law enforcement shootings by race are tough to come by, but statewide, according to 2018 numbers released by the Office of the Attorney General, about 47% of those affected by incidents that involved the discharge of a weapon or use of force resulting in death or serious injury were Latino.

Torres said East L.A. is in dire need of more resources to help families with police brutality and more oversight of the Sheriff’s Department, particularly from county officials.

“I think Hilda Solis is fighting in her own way,” Torres said of the L.A. County supervisor. “She came out and denounced what happened to George Floyd. That’s commendable, but what about your own backyard? There’s so much happening here, too.”

Solis, whose district oversees East L.A., said her office is aware of community frustrations with the Sheriff’s Department. She holds Sheriff Alex Villanueva accountable.

“He really needs to take a close evaluation of the people he has at the East L.A. station,” she said. “He came in with a lot of rhetoric, but he’s not listening. ... He’s inciting and harassing and intimidating, trying to shut the voices out.”

Solis said she and others established the Sheriff Civilian Oversight Commission and granted them subpoena power to try to keep the office in check. She also said she supported the inspector general investigating the department.

“I even went as far as holding his budget,” Solis said. “But he’s not been responsive.”

For mothers pushing for answers about their sons’ deaths, it’s been a battle, said Leah Garcia, whose son was shot and killed by deputies last summer during an altercation after a traffic stop.

“At the end of the day, we’re all in this together. Black lives matter. Our sons’ lives matter. But when you see no change, it feels like a harder, lonelier fight.”

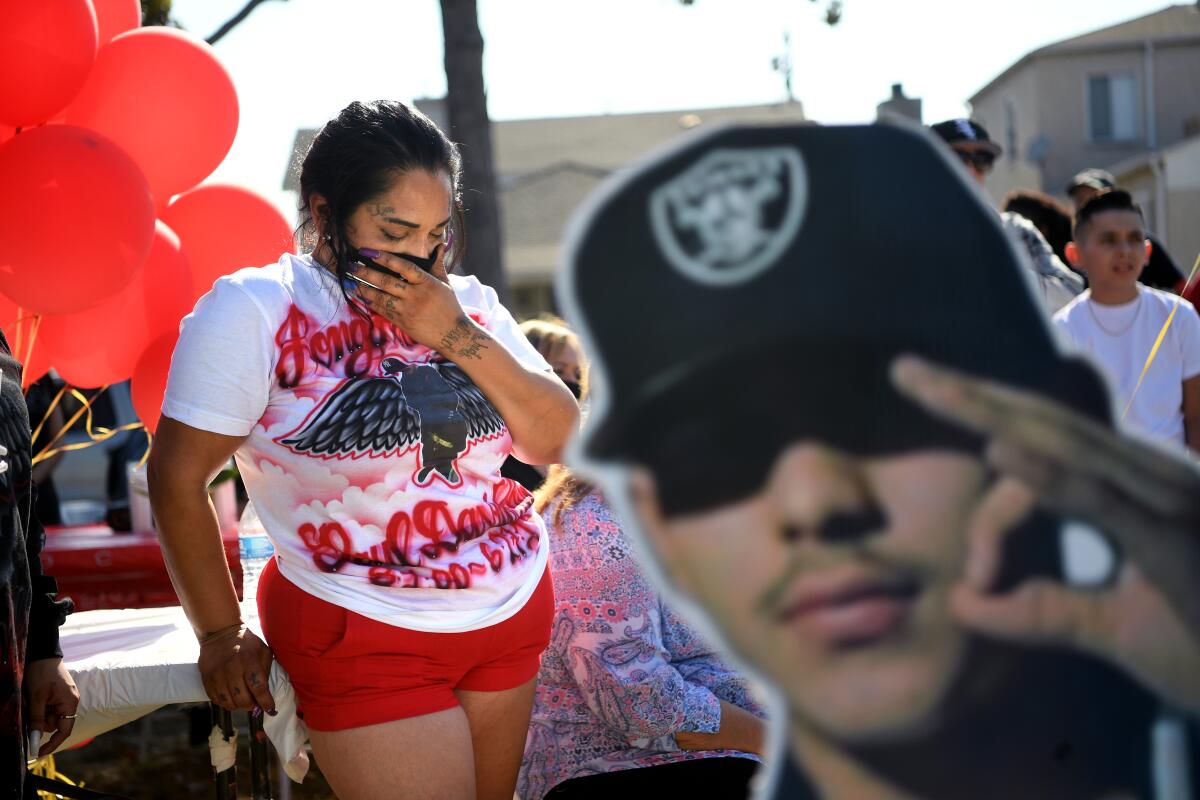

The grieving mothers in her group are the only ones who understand the trauma, she said. Together, they keep a running calendar of their sons’ birthdays and the anniversaries of their deaths. They hold Masses at one another’s homes or vigils where their sons were shot down.

At home, many put up altars as a tribute. Garcia keeps her son Paul Rea’s image everywhere: His portraits hang on her walls. His life-size cutout stands in her living room. Stickers of his face deck her laptop and her car.

The group has gotten support from those in the Black Lives Matter movement and also from the American Civil Liberties Union, but most days, their efforts are spontaneous and informal, without too much thought for an overall strategy.

Most of the moms hardly consider themselves activists. Some struggle with their English. Others worry about their immigration status. A few have faced criticism for posting their son’s image on social media.

Still, staying home and staying quiet is not an option, so they carry rally signs and banners in their cars, always ready to bring attention to their cause.

At many protests — outside the Hall of Justice and the Sheriff’s Department — Lisa Vargas, a mother known for having a nice way with words, often leads the way. Her son Anthony Vargas, 21, was killed by deputies in August 2018.

The day Anthony was killed, Lisa was frantic. She said she had to wait nearly 24 hours at the site of the shooting before getting confirmation that her son had been killed. At some point, Moreno showed up and introduced herself. So did other women whose sons had been killed by authorities.

“They knew how I felt because the same thing had happened to them,” Vargas said. Weeks later, the women held one of their first protests. About 300 people showed up.

Vargas, like Moreno, now tries to rush over whenever there is a police shooting on the Eastside to offer her help. She connects families with attorneys willing to help or sets up money drives to cover funeral expenses.

Their goal moving forward, she said, is to reform the Sheriff’s Department, make it more transparent, have it provide better training to deescalate situations and get deputies to wear body cameras. Many women also want charges brought against the officer who killed their son.

Carlos Montes, an organizer with Centro Community Service Organization, began working with the moms a few years back. His Boyle Heights grass-roots group focuses on immigrant rights and education, but it shifted its focus to police brutality after a rash of killings in 2016.

At 77, Montes has a long history of activism on the Eastside. He’s been protesting sheriff’s deputy misconduct for five decades, dating back to the Chicano civil rights movement and through the Rodney King uprising. Over the years, he said, he’s seen moms in East L.A. and Boyle Heights take on leadership roles to fight gangs, the construction of prisons and toxic environmental waste sites.

This is the first time he recalls a group of women holding law enforcement accountable for killing people.

“These mothers are taking on the big guns,” he said. “They’re going up against forces that others consider too controversial. I’m inspired by them.”

Three years after her son Cesar’s death, Moreno struggles with how little she’s accomplished.

She constantly plays out the day Cesar walked out of their East L.A. home to head to Long Beach. Three days later, after not hearing from him, she learned that her son had allegedly not paid his train fare and reportedly ended up in a struggle with a Long Beach police officer. Cesar wound up pinned between a train and the platform. Moreno filed a federal wrongful-death lawsuit in April, alleging assault and battery, excessive force and inadequate training.

For days after his death, Moreno said she lost her voice. “I couldn’t get a word out. I hardly recognized myself or anyone around me,” she said.

Now, when she feels adrift, she calls on the other mothers. She marches alongside them.

“No matter what happens, I know I’m not alone,” Moreno said. “I see myself reflected in them.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.