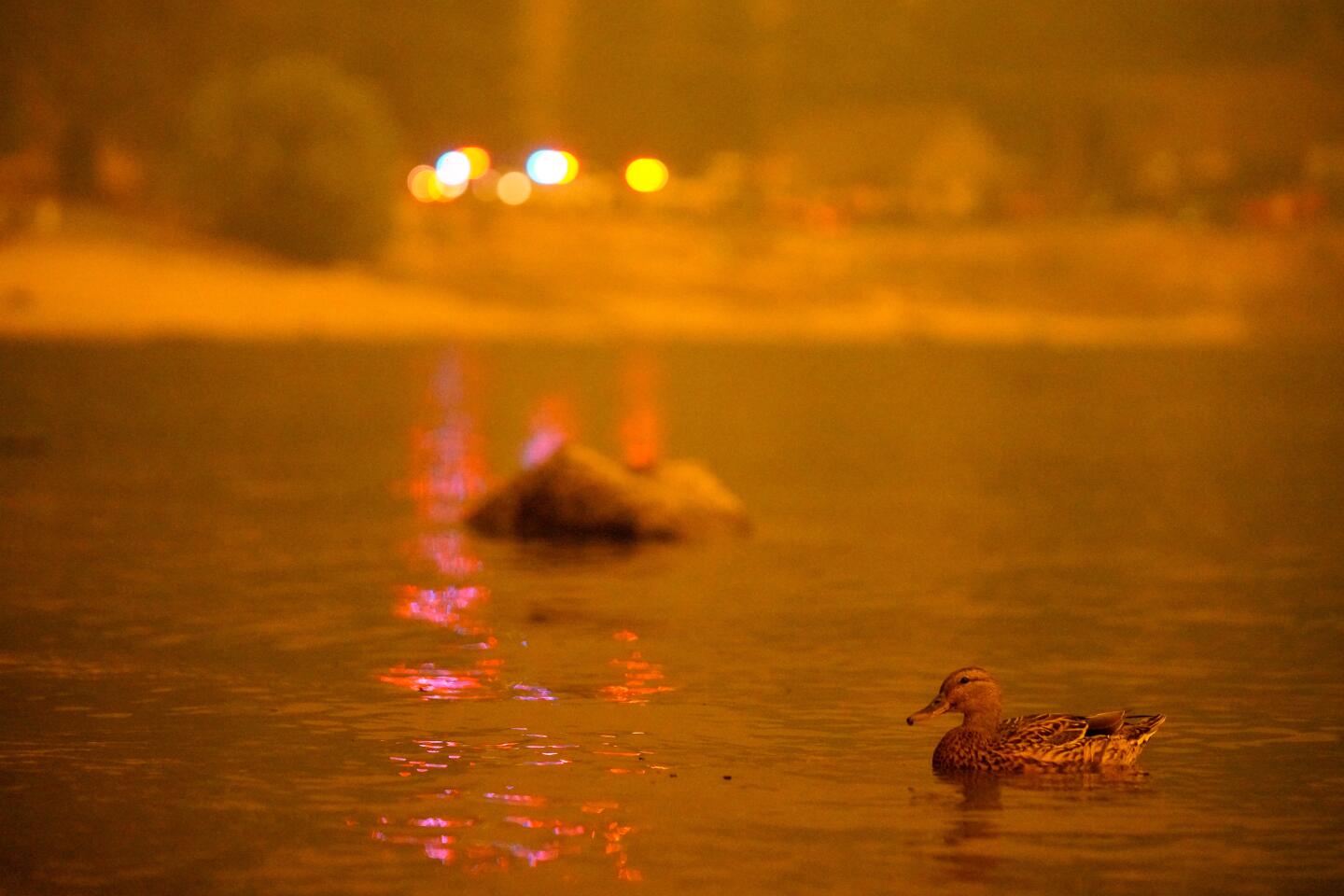

Daring escapes, wrenching devastation as ‘the fire is blowing up everywhere’

- Share via

Wildfires of historic magnitude have led to daring escapes and wrenching devastation.

- Share via

CLOVIS, Calif. — In the Sierra Nevada, helicopters evacuated more than a hundred people trapped by flames. In the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains, thousands of residents worried that Santa Ana winds could push the growing Bobcat fire into their communities. And in Sacramento, Gov. Gavin Newsom warned the populace that state resources would be severely taxed by dozens of wildfires now raging across the state.

California’s record-breaking wildfires continued to rage Tuesday even as authorities conceded they would likely get much worse as downslope winds from Shasta to San Diego prompted red flag warnings. The dire predictions come as more than 2 million acres have been burned since July and as Californians recover from a withering weekend of record heat.

Since the Creek fire broke out Friday night in the Sierra foothills, it has raced through pine forest and thick underbrush to become one of the largest wildfires in the state this year, with no containment.

Starting at 3 a.m. Tuesday, the National Air Guard and Naval Air Station Lemoore sent two helicopters — a Blackhawk and Chinook — to evacuate 142 campers and hikers from Edison Lake, making eight trips to get all of them out. Coordinating with the Fresno County sheriff, crews were planning to rescue 62 more people throughout the day.

The fire ripped through timber made more flammable by the bark beetle infestation, cutting across Highway 168, the main road between Shaver and Huntington lakes. With that route closed, fire crews were divided as they fought to save the cabin communities along the lakes.

“The fire is blowing up everywhere,” said Christopher Donnelly, chief of the Huntington Lake Volunteer Fire Department, speaking on the phone Monday.

The erratic, increasing winds and steep terrain pushed the fire into multiple fronts and forced firefighters into a triage situation in deciding which of the many small mountain hamlets they could protect.

“Crews have been working a 96-hour shift,” said Nathan Magsig, Fresno County supervisor for the foothill district. Magsig spoke onsite at Shaver Lake, where evacuations had taken place.

In Southern California, Santa Ana winds were expected to build up throughout the night, potentially pushing three major fires toward populated areas: the Bobcat fire, burning in the San Gabriel Mountains above Monrovia; the El Dorado fire, near Yucaipa; and the Valley fire, southeast of Alpine in San Diego County near the Mexican border.

Firefighters in San Diego worked to build fuel breaks on the west front before the winds were expected to kick up around 8 p.m.

“We have a sleeping giant that is in the backcountry,” said Tony Mecham of the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection. “And while we have focused tremendous effort on the west side of the fire, tonight the winds are gonna blow. And this fire has the potential to burn.”

San Diego County Supervisor Dianne Jacob warned residents to be ready to evacuate and sought to reassure those who might be reluctant to go to a shelter because of fears about the coronavirus, saying that emergency officials were taking steps to protect people’s health.

“We have a plan, which includes hotel rooms, congregate shelters, when needed,” she said. “So please know that precautions will be taken to protect a person’s health and safety at the evacuation centers and hotels, or wherever they may be placed safely.”

In Los Angeles County, fire officials feared the wind could push the Bobcat fire into foothill enclaves such as Cloverfield Canyon in Monrovia.

The last time fire threatened the canyon, in 2009, Cliff Armstrong, 60, stayed behind, watering his house with a garden hose.

“I don’t think I’ll risk it this time,” he said.

Neighbors were packing up cars and moving vehicles to the homes of friends. One told Armstrong he removed all the cushions around the patio, and floor mats — anything that was combustible.

“Oh, right, right,” Armstrong replied. “Well, wait a minute. I have garage full of toilet paper and paper towels because of the COVID thing, man.”

Forest Service officials announced the closure of eight national forests — Angeles, San Bernardino, Los Padres, Cleveland, Stanislaus, Sierra, Sequoia and Inyo — at 5 p.m. Monday because of the extreme heat and dangerous conditions.

“Existing fires are displaying extreme fire behavior ... and we simply do not have enough resources to fully fight and contain every fire,” said Randy Moore, regional forester for the U.S. Forest Service.

Fire activity has been particularly prolific since Aug. 15, which marked the start of a “lightning siege” that unleashed thousands of lightning strikes statewide.

Since just that date, firefighters have battled more than 900 blazes that have burned 1.8 million acres, Gov. Gavin Newsom said. Eight people have died during the weeks-long firestorm, and roughly 3,400 structures have been destroyed.

“This is a challenging year,” Newsom said. “It’s historic in terms of magnitude, scope and consequence, and it also has required ... a deep reservoir of resource.”

On Tuesday, nearly 14,000 firefighters were contending with 25 major wildfires, according to Cal Fire, and the agency had increased staffing in preparation for critical fire weather in several areas.

The most dangerous at that point was the Creek fire in the Sierra, which had grown to more than 150,000 acres. Fire crews at Huntington Lake had been extinguishing small spot fires and had hoped to have three bulldozers cutting breaks along the north shore of the lake, said Donnelly, the volunteer fire chief. But as the fire pushed closer to Shaver Lake, and with Highway 168 impassable, the crews were left with only one dozer for the job.

Strike teams at Huntington Lake were redirected to Shaver Lake, as well as the western front, a rugged region known as Jose Basin that could channel the fire closer to the communities of Tollhouse and Prather and farther toward Auberry.

“The Forest Service has worked heroically to remove dead trees from the bark beetle,” said Donnelly. “But there are millions of trees, and they haven’t done anything to clear forest above these cabins. With so many surface fuels, it is almost impossible to stop a fire running through them.”

By Tuesday afternoon, the fire front was threatening to surround Shaver Lake. Fire ecologists are certain to study this fire because it is burning through areas that were commercially logged under a U.S. Forest Service program meant to revive the timber industry in depressed mountain towns and reduce the risk of catastrophic fire.

“We had pleaded with the Forest Service not to approve those logging operations in the Sierra National Forest because they would not prevent fires and would likely make future fires burn hotter and faster,” said Chad Hanson, a research ecologist with the John Muir Project. “The agency ignored us, so we filed lawsuits in 2014 and 2015 to stop them, but federal judges deferred to the Forest Service.

“On Saturday, the speed of the Creek fire as it burned through the areas that had been logged under the guise of fuel reduction was the fastest I’ve seen in two decades of studying wildfire behavior,” he said, with one exception: “the Camp fire in 2018, which spread at a similar speed through several thousand acres that had been heavily logged in previous years, devastating the community of Paradise.”

Times staff writers Joe Mozingo and Louis Sahagun contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.