In D.A.’s race framed by reform, George Gascón’s police career is under a microscope

- Share via

Less than two years into his career as a Los Angeles police officer, George Gascón said, he saw a suspect reach for his partner’s gun as they struggled to arrest him.

At the time, most LAPD officers carried their weapons in what is known as a pancake holster. Gascón said he knew the suspect wouldn’t be able to pry the gun loose if he squeezed the holster tight, so he grabbed for the soft leather casing instead of drawing his own weapon. Deadly force would have been justified, but Gascón said he didn’t want to take a life if he could avoid it.

The LAPD disagreed, according to Gascón, who said he received a disciplinary letter questioning his tactics.

The incident would come to shape his thinking on the culture of policing, as an officer and later as district attorney in San Francisco.

“That really had an impact on me over the years,” Gascón said. “A police officer should use force when they should, not just because they can.”

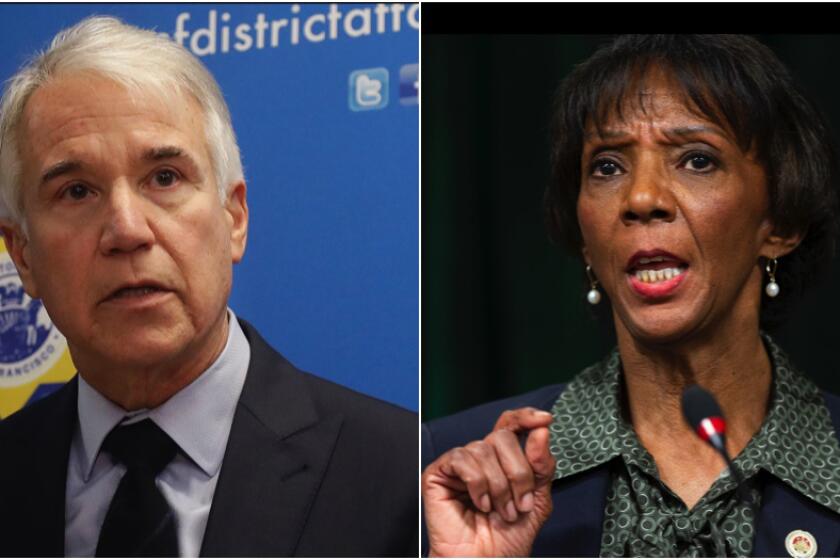

At a time when police violence is under scrutiny and many are calling for an overhaul of the criminal justice system, Gascón’s image as a reform-minded law enforcement veteran has given life to his bid to unseat Jackie Lacey as Los Angeles County’s district attorney this November.

The November contest between Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Jackie Lacey and former San Francisco Dist. Atty. George Gascón to oversee the nation’s largest prosecutor’s office has been framed as a test of appetites for criminal justice reform.

But the attention also has led some to spotlight decisions Gascón made as a police officer that critics contend belie his progressive rhetoric.

Gascón’s policing career spans three decades. After joining the Los Angeles Police Department in 1978, he rose through the ranks and became an assistant chief in 2003 before leaving to serve as chief of police in Mesa, Ariz., in 2006. He was hired as San Francisco’s top cop in 2009 before being appointed as district attorney.

Public records and interviews with those who worked closest with Gascón in each city suggest that while he was able to achieve his progressive agenda and make public safety gains as a police chief in Arizona and the Bay Area, instances from his LAPD days have lent ammunition to those who question his vow to hold police accountable.

“The tragic death of George Floyd has rightly shifted the debate to a debate about police accountability and misconduct,” said Walter Koch, who came on as Lacey’s campaign coordinator after the March primary. “I think the voters have the right to know the record of a candidate in this race who is presenting himself as a reformer.”

Recent attacks by the Lacey campaign have focused on disciplinary decisions Gascón made as an LAPD commander, including in the 1999 shooting death of Gus Woods.

An LAPD officer was responding to a disturbance call when he encountered Woods, 56, who he believed was advancing toward him with a knife. Woods was standing about 22 feet away when the officer fatally shot him. Investigators later determined Woods was armed with a metal rod, not a knife.

Both the city’s civilian Police Commission and then-Chief Bernard Parks found the shooting “out of policy,” but a disciplinary board led by Gascón ruled the officer had not violated LAPD use-of-force rules. Prosecutors declined to charge the officer.

At the time, Gascón said he based part of his decision on the fact that the officer had been shown an unauthorized training video focused on the “21-foot rule,” which instructs that deadly force is reasonable against a suspect armed with an edge weapon less than 21 feet away.

Police boards overruled commission’s findings that four shootings were improper. Panels have a history of meting out uneven penalties.

In a recent interview, Gascón said that he did not believe the shooting was justified but felt it was unfair to punish an officer influenced by a video “widely spread through” the LAPD. More broadly, Gascón said it was unreasonable to judge his stances in 2020 based on decades-old decisions.

“It’s like saying that a human being is incapable of growing and learning, which I find a very narrow way of thinking,” he said.

Picking apart Gascón’s record on police discipline is difficult because California law limits access to such records except in cases of serious uses of force, lying and sexual assault. Gascón had not been disciplined for any such conduct, according to the LAPD and San Francisco police.

A document the LAPD turned over in response to a public records request shows Gascón sat on 11 LAPD disciplinary boards between 1996 and 2006. Officers were punished for misconduct in four of those cases, but the document does not reveal how Gascón voted.

Parks, who supports Lacey, told The Times that Gascón did not have a significant “disciplinary history” from his time in the LAPD. A review of Gascón’s personnel file in Mesa, where police disciplinary records are public, found no allegations of misconduct.

Parks said he believes Gascón was lenient when he sat on disciplinary boards and dismissed his progressive stances as “inauthentic” and mostly designed to benefit his political aspirations.

“It would not be past him to go to a community meeting and ingratiate himself. But the community doesn’t necessarily follow his day-to-day steps,” Parks said. “So when he was confronted with the very situations he said he would do something about, he didn’t.”

Connie Rice, a civil rights attorney who co-founded the LAPD’s Community Safety Partnership program, said Gascón was an ally to community leaders and did not fit the “insular, true blue LAPD straitjacket.”

“I was representing minority officers who were suffering race discrimination inside of LAPD, and we would talk about what it would take to change how LAPD operates,” she said, adding that Gascón was one of a few “inside mavericks” who used his position “to challenge the culture rather than perpetuate it.”

Gascón said his refusal to accept the status quo in policing was borne out of his upbringing in Cuba, where he says he saw firsthand what “oppressive policing and government can do to a country, to a people.” He said he learned to speak out from his father, who was a vocal critic of Fulgencio Batista and Fidel Castro before the family fled to the U.S. in 1967.

Former LAPD Chief Charlie Beck, who has endorsed Gascón, praised him for pushing community-oriented approaches to stopping gang violence. He dismissed suggestions that Gascón was lenient on discipline on the Board of Rights review panels.

“The Board of Rights for George was always about the truth,” Beck said. “If you were guilty, he is the worst person for an officer … but if evidence favored you, he’d listen.”

Gascón’s leadership was criticized in a report detailing the LAPD’s disastrous response to the 2007 May Day protests that left hundreds of people injured as police indiscriminately swung batons and fired projectiles into crowds. Though Gascón had left the LAPD in 2006, the report noted he had cut back on crowd-control training in the years leading up to the fiasco.

The chief apologizes for flawed leadership during the May 1 rally. A new report says at least 26 are under investigation.

Gascón disagreed with the report, noting he had ordered officers to stop responding to protests in riot gear after the LAPD was criticized for its handling of antiwar demonstrations in the early 2000s. Gascón also said he had personally been on the front lines in response to past May Day protests that ended peacefully.

After leaving Los Angeles, Gascón was given his first chance to institute a reform agenda as chief in Mesa. Throughout his four-year tenure, Gascón repeatedly locked horns with Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio, the anti-immigrant lawman who was later convicted of contempt of court for illegally detaining undocumented immigrants.

Despite the political loggerheads, activists and former colleagues spoke highly of Gascón’s tenure. Records show homicides fell by half from 2006 to 2009, while aggravated assaults dropped by 21%. In a 2008 performance review, Mesa City Manager Chris Brady said the police force had been “demoralized” and “poorly structured” before Gascón “created systems to enhance employee accountability and internal communication.”

Gascón revised the department’s use-of-force policy, while instituting the LAPD’s high-tech CompStat model to improve the agency’s ability to track crime data.

Andre Miller, a longtime criminal justice activist and pastor at New Beginnings Christian Church in Mesa, said Gascón helped heal a rift between the department and the community.

“The community engagement piece, that was something that was very lacking. Mesa has a history of being heavy-handed in terms of force, but he came in and he really brought the community to the table and had hard conversations that were necessary,” Miller said. “I also think he set a different standard for his police officers than had been set before.”

Though Gascón’s time in San Francisco is more often associated with his role as district attorney, his 18-month stint as the city’s police chief also radically changed the historically insular agency, current and retired officers in the Bay Area said.

Capt. Yulanda Williams, president of San Francisco’s Officers for Justice, an association of Black police officers, said Gascón came in with a reform mandate and immediately targeted longtime structural problems with the agency’s disciplinary system.

“He took police misconduct seriously and he made some changes in the Internal Affairs Division and tried to make it be far more professional,” she said. “Those who were in command staff, he started to hold them far more accountable because he wasn’t part of the legacy eras of SFPD.”

Gascón’s term from mid-2009 to January 2011 was also marked by a sharp drop in homicides. San Francisco reported nearly 100 murders in 2008 but 48 in 2010. Gascón says he inherited a department that solved only 25% of its slayings, with a homicide bureau that lacked structure and supervision.

As chief, Gascón said, he broke up the city’s centralized homicide bureau and placed investigators in districts, which allowed detectives to focus on repeat offenders.

“There were people committing multiple murders who were not being held accountable, and solving those cases had a tremendous impact overnight,” Gascón said.

Though he has championed diversion and leniency for low-level drug offenders and homeless defendants as a prosecutor, Gascón also oversaw large-scale sweeps in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood as police chief. The move drew fierce criticism from progressives, including former Public Defender Jeff Adachi, who claimed Gascón was unnecessarily clogging San Francisco’s courts and jails with people accused of minor drug crimes.

Chris Breen, who served as sergeant-at-arms for the union representing San Francisco police officers in 2010, said that although Gascón oversaw a marked decline in crime as chief, he also employed a “dictatorial” style and rarely took advice from Police Department veterans before making major changes.

Though Breen applauded some of Gascón’s reforms — including providing treatment for officers arrested on suspicion of DUI rather than just suspending them — he said the chief at times took his reform mandate too far.

Gascón furthered the use of what Breen believed was an overzealous system that placed officers under scrutiny if they received multiple citizen complaints, even if the complaints were not sustained. Breen, who retired in 2015, said the policy counted involvement in police pursuits and instances in which suspects resisted arrest as negatives against officers.

“He was the great reformer. ‘I’m from LAPD. I know better. My department’s bigger than yours; we are very successful. We are very militaristic, and that’s what I want SFPD to be like,’ ” Breen said.

In 2010, Gascón’s only full year in charge of the department, San Francisco police upheld about 8% of all citizen complaints, in line with the average for police agencies across California, records show. The department had upheld 5% of those complaints the year before.

Gascón believes accounts from the allies and enemies he made during the decades he spent wearing a badge make clear his progressive tendencies manifested long before he decided to run in L.A.

“There is no question that I am a different person today than I was 20 years ago, and that evolution will continue … but this evolution just didn’t happen yesterday,” he said. “The reality is I’ve put a lot of blood on the altar.”

Times staff writer Richard Winton contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.