Detainees at California’s for-profit ICE detention centers will soon be able to sue over abuse, harm

- Share via

Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a bill Sunday backed by immigrant-rights advocates that mandates greater accountability by the companies that operate federal detention facilities in California.

Assembly Bill 3228 allows people to sue private detention facility operators for failing to comply with the standards of care outlined in the facility’s contract and to collect “reasonable” costs and attorney’s fees. The bill is the first of its kind in the nation, supporters say. The law takes effect Jan. 1.

It’s the latest twist in an ongoing fight pitting California leaders against federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials and the corporations that manage the four immigration detention facilities in the state.

Advocates say that private prison companies have been shielded by an oversight scheme that allows them to violate the minimum standards of care. Last year, inspectors at the Department of Homeland Security found that ICE doesn’t adequately hold detention facilities contractors accountable for failing to meet those standards and had imposed financial penalties only twice in nearly three years.

“The highest level of scrutiny should be placed on any for-profit entity,” said Hamid Yazdan Panah, advocacy director for the nonprofit Immigrant Defense Advocates, which sponsored the bill. “We have to be certain that they’re not placing profit above human lives.”

Paige Hughes, a spokeswoman for ICE, said Monday that the agency’s legal experts were reviewing AB 3228. She said ICE adheres to “an aggressive inspections program” for detention centers.

“Any law or policy enacted based on misleading information and false allegations only serves to distract the general public from the facts,” Hughes said. “Policymakers who strive to make it more difficult to remove dangerous criminal aliens by preventing ICE from procuring suitable detention space within a state or locality simply increase taxpayer costs and force ICE to transport detainees to more remote locations.”

Immigrant detainees currently can sue the federal government for damages over civil rights abuses under the Federal Tort Claims Act, which does not apply to private prison companies, said Eunice Cho, an attorney with the National Prison Project at the American Civil Liberties Union.

So while many federal lawsuits have been brought against ICE over alleged mistreatment of detainees in California facilities, it was more difficult to bring similar claims against the companies managing those facilities on ICE’s behalf, she said. The new legislation cements a clear path under state tort law and clarifies the standard of care that must be provided.

AB 3228 builds upon AB 32, which banned new private prisons and detention centers after Jan. 1 and called for existing facilities to close by 2028.

Days before AB 32 took effect, ICE officials signed contracts totaling nearly $6.5 billion with the three companies that operate the agency’s California facilities. The contracts have terms of 15 years, including two five-year extensions, ending in 2034.

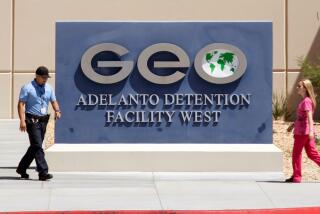

ICE and one of those companies — the GEO Group — sued the state, arguing that AB 32 is unconstitutional. GEO, one of the country’s largest private prison operators, manages ICE facilities in Adelanto and Bakersfield.

In a tentative ruling in July, a federal judge in San Diego suggested that she was likely to dismiss most of the case against California and uphold the law.

According to reports filed with the California secretary of state, GEO spent a combined $73,400 from January through June lobbying against AB 3228 and another bill that sought to expand access to legal counsel in immigrant detention centers but did not advance in the Legislature.

AB 3228 comes amid increasing reports of medical neglect and abuse inside private detention facilities across the country. Last week, the House Committee on Oversight and Reform released the results of a 14-month investigation into for-profit ICE contractors, which found that several detainees died after receiving inadequate medical care, including one man who died at the Adelanto detention facility northeast of Los Angeles.

Assemblyman Rob Bonta (D-Alameda) authored both AB 32 and AB 3228. He called the signing of AB 3228 a victory for human rights and for justice.

“For-profit private detention centers must be held accountable in the face of egregious human rights violations and harm to the health, safety and welfare of Californians, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic,” Bonta said.

Three companies operate ICE facilities in California. In addition to GEO, CoreCivic runs the Otay Mesa facility in San Diego and the Management & Training Corp. runs the Imperial Regional facility in Calexico.

Representatives for those companies said they have always been committed to treating detainees with dignity and prioritizing their health and safety.

A GEO spokesperson called the new law an attack on government contractors and said in a statement that the company is already subject to robust oversight from the federal government, third-party accreditation agencies and independent auditors. The company declined to provide the spokesperson’s name.

“This bill is nothing more than a distraction from the failed policies of the State of California and a politically motivated attempt to abolish ICE by undermining its ability to carry out its mission in California,” the spokesperson wrote.

At the privately run facilities in California, 306 ICE detainees have tested positive for COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic, according to ICE statistics, and the virus killed one man at the Otay Mesa facility in May. Civil rights lawyers have sued for the release of detainees at every facility in California.

Supporters of AB 3228 say that conditions in the facilities during the pandemic have proven the need for the new law. In June, detainees at Adelanto were pepper-sprayed for peacefully protesting ongoing lockdowns. Detainees there say they’ve experienced nose bleeds, burning eyes and nausea because employees consistently spray a hazardous disinfectant against its recommended use indoors.

Advocates said they are also concerned about potential expansions of two detention centers in California.

Officials in the Central Valley city of McFarland voted earlier this year to convert two former prisons into annexes for the nearby Mesa Verde ICE facility, adding 1,400 beds to its previous capacity of 400. Immigrant advocates sued, but ICE began temporarily filling one of the annexes this month after a judge ruled in its favor.

Also earlier this month, the Adelanto City Council deadlocked on a vote over whether to approve a similar conversion of a former 750-bed prison into an annex for the 1,940-bed Adelanto ICE facility. The city’s attorney upheld an earlier planning commission decision approving the conversion, green-lighting the expansion.

Advocates sent a cease-and-desist letter to Adelanto city officials, charging that the approval is unlawful. If it ultimately moves forward, the Adelanto facility would become the biggest in the country.

The path for these potential expansions was paved through the contracts signed just before the private prison ban took effect. Though the facilities will remain open for now, Bonta said, it’s only fair that they be regulated by the state that wants them out.

“As long as they are operating, they will be held accountable by AB 3228,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.