- Share via

Konstantinos Varelas twisted a string of blue komboloi — Greek worry beads — outside his family’s restaurant on Main Street in El Monte.

The son of Greek and Mexican immigrants, Varelas was a child when his father bought Golden Ox Burgers. Back when the street was more alive. Back when they could count on people popping in for a pastrami sandwich or a quesadilla.

Now, plexiglass divides workers from customers, who have their temperatures taken at the door before picking up food to go. The staff has been cut in half. People walk by less and less. And he fidgets more and more with the worry beads he carries all the time in this pandemic year.

“When Dad first got the restaurant, it was so busy you couldn’t walk along the street right here,” Varelas, the 23-year-old restaurant supervisor, said wistfully. “It used to be full of life and busy. Now, we’re lonely, I guess you could say.”

Eight miles away, Aldo Santos wore a blue surgical mask while walking back to work after lunch. He lamented the quiet on Colorado Boulevard in Pasadena, where the Rose Parade has been canceled, stores keep closing, and the marquee outside the stately 1924 First United Methodist Church building reads: “Via Livestream Only.”

“Colorado Boulevard is the main artery of Pasadena; everything comes through here. It’s been that way forever,” said Santos, 64. “But it’s not the same. I can’t say it’s a ghost town. It’s not empty, but it’s probably at 50%. Everyone’s just trying to survive.”

Eight months into the ever-worsening COVID-19 pandemic, the same can be said of Main Streets across California, which groan with anxiety as winter sets in, coronavirus cases soar, and “for lease” signs become more abundant in shop windows.

From the quaint Myrtle Avenue in Monrovia to the dying strips of old Gold Rush towns to the bucolic Main Street, U.S.A., in the still-closed Disneyland to the famed Colorado Boulevard — part of Route 66, dubbed the Main Street of America — these are places that invoke a sense of a more prosperous yesteryear. A time when mom-and-pops thrived and community was at the center of everything.

Now, Main Street, both as an idea and a place, is fragile.

Oases of calm predictability against the often choppy swells of an urban sea, they are also replete with the kinds of small shops that the pandemic has sunk.

“People love community. They love sidewalks. They love streets with activity,” said Miles Orvell, a Temple University professor and author of “The Death and Life of Main Street: Small Towns in American Space, Memory and Community.” “They love the idea of living in a place that has a sense of identity.”

Paul Little, chief executive of the Pasadena Chamber of Commerce, said he worries about already-struggling restaurants surviving a new suspension of outdoor dining and about retail stores getting by with county-imposed limits on customers right before the holidays. He fears an “avalanche of closures” in early 2021 after eviction moratoriums expire.

“Unique locally owned and operated places are the ones most at risk, but also the ones that contribute most to the character of Pasadena,” Little said. “Once they’re gone, they’re very difficult to get back.... What are we without them?”

“The assumption always was, if you see an empty storefront on Colorado, give it six months and someone else will be there,” Little added. “I don’t know if that’s the case anymore.”

While the 88 cities within Los Angeles County can seem like one massive stretch of urban sprawl, the Main Streets of its smaller locales are places set aside from the hustle and bustle of big-city life, places where there is “a positive sense that life can be sanely meaningful,” Orvell said.

“The small-town Main Street still represents something different,” Orvell said. “It’s smaller, but it’s also an entity in itself, so it feels ‘whole,’ in a way.”

On a sunny afternoon last week, Don Vena sat on a park bench beside Myrtle Avenue in Monrovia. The 76-year-old retired pastor and substance abuse counselor wore a baseball cap with the letters JC, for Jesus Christ, tapped his foot and smiled as a man played bongos nearby.

Vena, who moved to Monrovia in 1980 to raise his family, comes to the park outside the public library at least once a week to enjoy people, friends and strangers alike. And he and his wife walk Myrtle Avenue every few days to eat and shop.

“I look forward to the little serendipities that come my way in my little small town,” Vena said.

These days, though, he worries about small businesses making it through this pandemic and that people will have gotten used to the ease of ordering online instead of shopping locally.

“I don’t want to see the end of the small town,” he said. “We need it as human beings. We are built to need each other, to interact and challenge and stimulate each other, to love one another.”

Nearby, a banner that said “Optimism Is Not Canceled in Old Town Monrovia!” touted shopping locally online, and ordering takeout. The marquee for the closed Studio Movie Grill read, “We will see you soon at the movies,” even though the small theater chain filed for bankruptcy last month.

Unlike on Wall Street, a lack of data hides the pandemic’s true toll on American Main Streets because many small businesses simply board up without going through bankruptcy court, said Nick Shields, an analyst for the investment research firm Third Bridge. Smaller retailers, he said, are having a harder time than big-box stores dealing with COVID-19 restrictions, paying for personal protective equipment and transitioning to online shopping.

But while the year is ending on a bleak note, there is also a tepid “wait-and-see environment” on Main Street amid the good news about the development of multiple promising vaccines.

“Now that we see the proverbial light at the end of the tunnel, there’s the feeling that if we can hang on until the spring, we’ll be OK ... and we’ll do whatever it takes to maximize the holiday season, even though we realize it’s going to be more challenging,” Shields said.

“People love community. They love sidewalks. They love streets with activity. They love the idea of living in a place that has a sense of identity.”

— Miles Orvell, a Temple University professor and author

In El Monte, the pandemic is a blow to a Main Street that has tried to mount a comeback in recent years. In 2017, the city reverted the name of the street known as Valley Mall back to Main Street to signal hopes for the kind of vibrant downtown that once was.

“My motivation was to go back to the roots of our city, what we had, when Main Street was a place where people would congregate, a one-stop shop with different products and services, a place where the community could come together,” said outgoing Mayor Andre Quintero. “That space brings you back to the time when it wasn’t that big, when everybody knew each other.”

Quintero, who grew up in the city, envisions a pedestrian-oriented corridor, with event spaces, high-density housing for young professionals, and thriving small businesses. But that takes a lot of investment, and progress has been slow, he said.

In an effort to woo people to the area in this cruel year, he said, the city has tried to get creative with the outdoor space, hosting drive-in movie screenings — called Movies on Main — in a parking lot, launching a farmers market and holding a drive-through Halloween celebration.

Officials have tried similar outdoor events in Lancaster, where they have closed a section of its eponymous Lancaster Boulevard to vehicle traffic on Friday and Saturday nights and filled the street with tables and chairs to support local restaurants, said Chenin Dow, assistant to the city manager.

The city’s historic main street, which was rebranded as The BLVD, has undergone a dramatic makeover over the last decade. It included a pedestrian-friendly road diet that eliminated two lanes of traffic and introduced a speed limit reduction — and the opening of more than 40 new businesses.

“It has become the heart of the community,” Dow said. But the pandemic, she said, “has definitely been a challenge for our businesses; there’s no way around that.”

Outside the Laemmle Playhouse 7 art-house movie theater on Colorado Boulevard, which has been closed since March, faded posters advertise films whose titles seem appropriate this year: “Hope Gap” and “Burden.”

“This has been longer and more painful than anyone could’ve imagined,” said Greg Laemmle, president of the family-run chain of eight Laemmle theaters.

The company has laid off all but seven of its roughly 150 employees. In October, it sold the properties for the Playhouse 7 and the Royal Theatre in West L.A. to a commercial real estate company, making it a tenant in the buildings it once owned.

On Colorado Boulevard, the theater, which opened in its current location in 1999, has been part of a “vibrant, arts-oriented district” where it drew film buffs who saw three to four movies a month, Laemmle said.

Like many business owners, he sees a lot of uncertainty in a post-COVID world. Will there be pent-up demand to see movies? Will people feel safe being in crowds? Will the office workers, those who went out to eat and see films after hours, return to Colorado Boulevard?

Theaters already were struggling as more people streamed films at home instead of going to the theater, Laemmle said.

“Evolution happens constantly, but when an asteroid hits,” he said, “it happens a lot faster.”

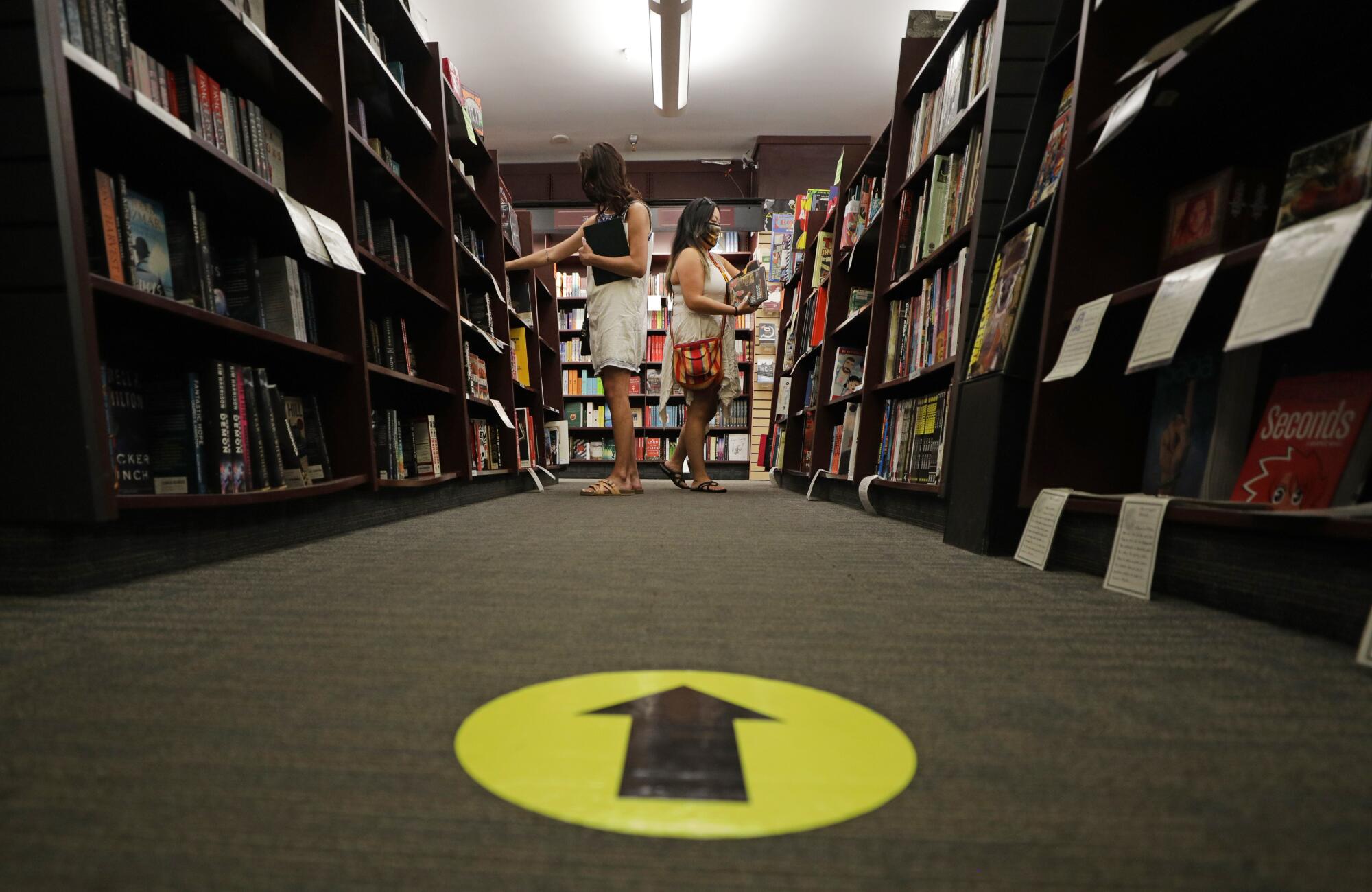

Next door to the Playhouse 7, the 126-year-old Vroman’s Bookstore is struggling. Two doors down, Roy’s Hawaiian Fusion Cuisine is closed. To walk west along the boulevard is to pass “for lease” signs in the windows of the Cajun restaurant Crackin’ Kitchen, the Peruvian restaurant Choza 96, the Lucky Brand store.

In The Dog Bakery, assistant manager Jocelyn Reyes frosted a heart-shaped buckwheat flour cake for someone’s pup and said the small shop is “one of the lucky ones.” Business has been booming this year because a lot of people now working from home got pets.

The bakery for dogs is thriving. But just next door, Cafe 86, a bakery for humans, closed up shop.

An apologetic sign on the door of Chef Tony Dim Sum, dated March 17, says it’s closed until further notice. In the window, wilted flowers droop.

Outside, a homeless man slumped next to a wall, his eyes downcast, his mouth covered with a cloth mask. A small handwritten sign was propped on the sidewalk next to him: “Everyone needs help sometimes.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.