Does a dry fall in Los Angeles always lead to a parched, fire-prone winter?

- Share via

After a summer of record heat and California’s worst fire season in history, Santa Ana winds have repeatedly buffeted the Southland during a critically dry autumn. Will this warm, dry weather pattern finally come to an end, or will it continue through the winter?

There’s a lot of evidence pointing to a dry winter, but it’s not a sure thing.

“The odds certainly favor a drier-than-average winter in Southern California,” said climatologist Bill Patzert, “but don’t bet your mortgage on it. Mother Nature can foil the forecasters.”

The case for a dry winter

Conditions are comparable to 2017, the season that was the third-driest year on record in Los Angeles, according to Alex Tardy of the National Weather Service in San Diego. In 2017-18, which was a weak La Niña year, L.A. received just 4.78 inches for the rainfall season, about 10 inches below average.

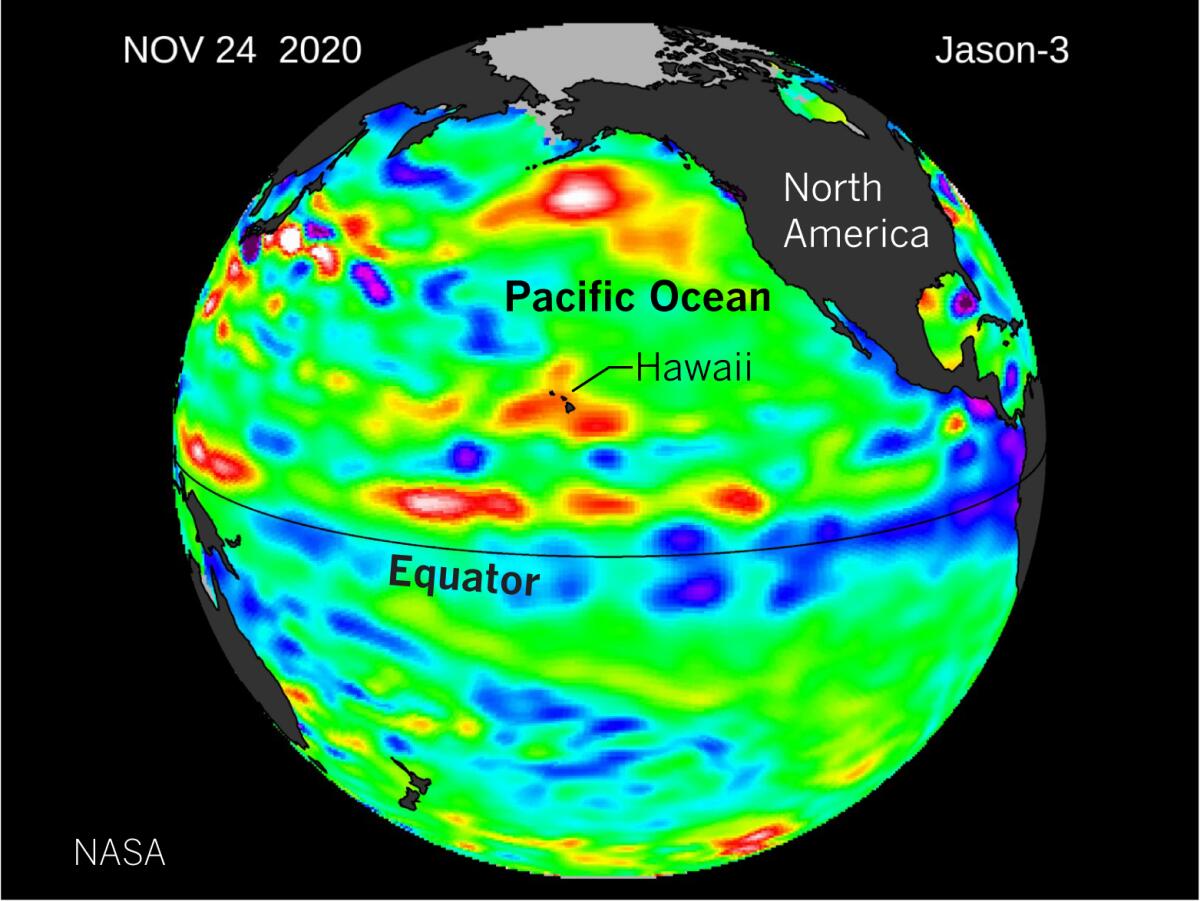

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, a La Niña is ongoing and strengthening in the tropical Pacific Ocean this year.

A La Niña occurs when the sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific are below average. Easterly winds over that region strengthen, and rainfall usually decreases over the central and eastern tropical Pacific and increases over the western Pacific, Indonesia and the Philippines. Statistically, a La Niña favors warmer, drier conditions across the southern tier of the U.S. and cooler, wetter conditions in the north.

The record Atlantic hurricane season this year is evidence of a strong La Niña in the Pacific Ocean. There are other features in the polar regions of the North Pacific that can influence California’s weather as much as La Niña, said Patzert, but generally, “when there are a lot of hurricanes in the East, the Drought Monitor lights up in the West.”

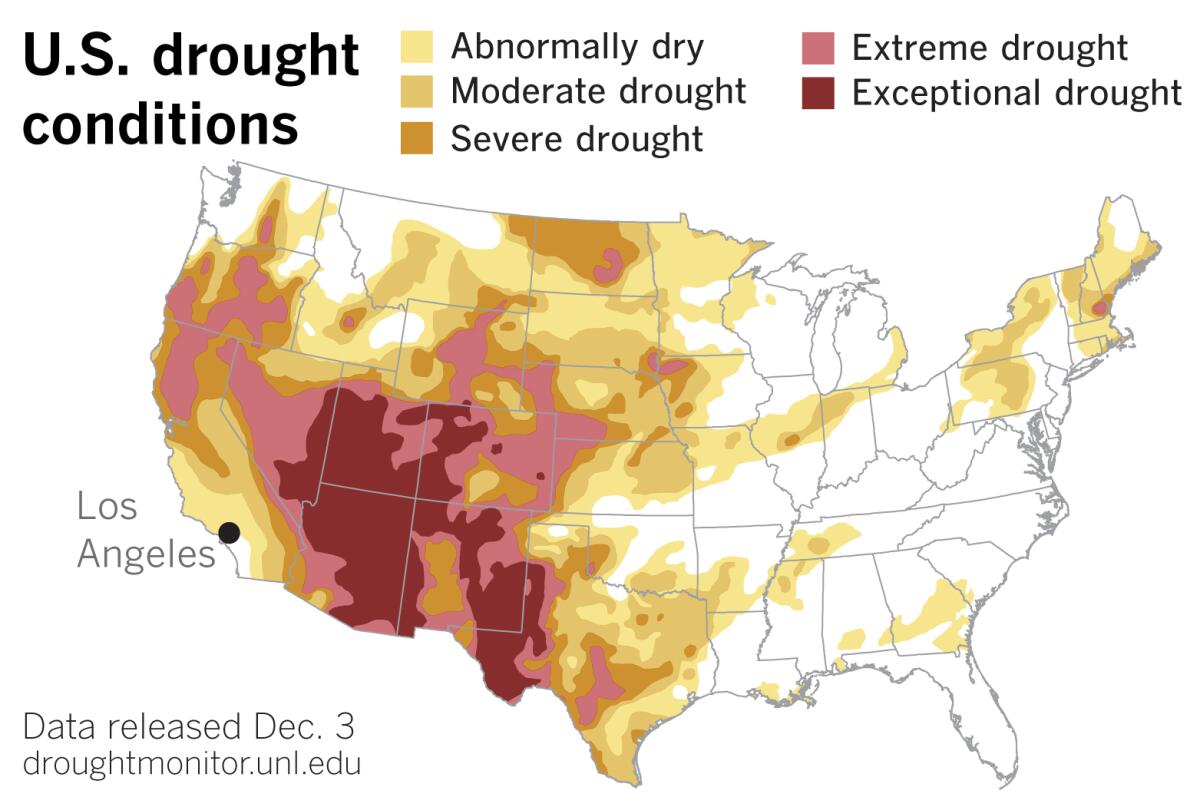

And the drought in the West is grave. The lack of summer monsoon rain resulted in extreme to exceptional drought in the Southwest. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, moderate to severe drought expanded in California’s San Joaquin Valley, and abnormal dryness expanded in Southern California, including Los Angeles County. Parts of Southern California have experienced a seven-month dry streak.

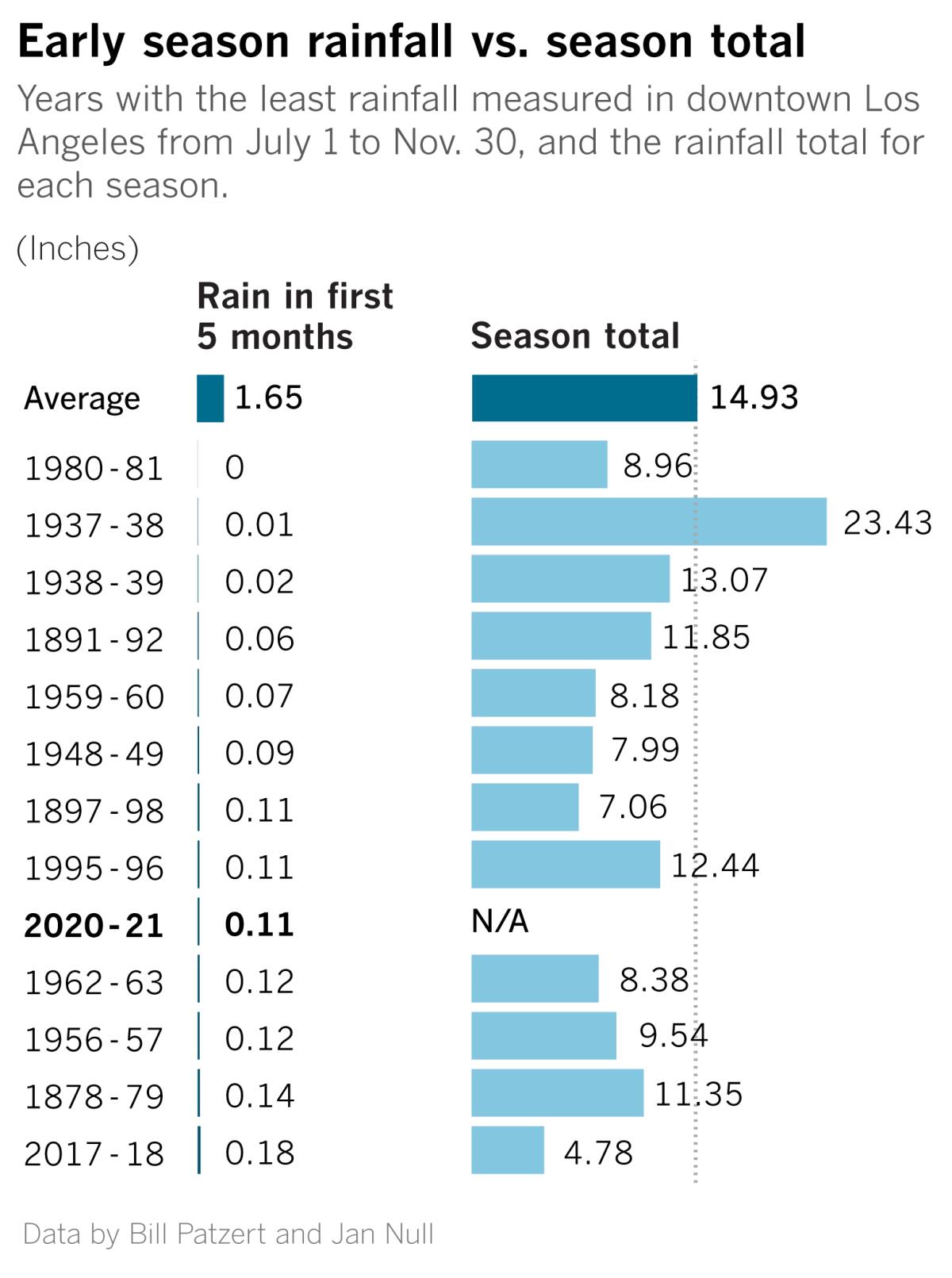

This season in Los Angeles, only 0.11 inch of rain has fallen. In an average year by the end of November, Los Angeles has received close to 1.7 inches. So L.A.’s rainfall this year is about 6% of normal. Taking a look at history, another dry winter is likely, Patzert said.

Patzert and veteran Bay Area meteorologist Jan Null took a look at the dozen driest July-November periods on record in L.A. They wanted to know how those seasons that started out so dry ended up. Southern California has a Mediterranean climate where it seldom rains during the summer.

Eleven of the 12 seasons with dry starts ended up dry for the rainfall year. So a dry autumn almost guarantees a below-average rainfall year.

But wait a minute ...

There is a notable exception in the chart above. The 1937-38 rain year started with an extremely dry autumn — only 0.01 inch from July to November — but it finished really wet: 50% above normal.

In a season that started out dry, the region was walloped by a couple of what were most likely atmospheric river storms in late February and early March — hardly what anyone hopes for when they think of being rescued by a March miracle.

On Feb. 27 and 28, Southern California got soaked with 4.4 inches of rain, according to Patzert. Then, on March 1, a new, more powerful storm dropped 10 inches of rain on L.A., with more in mountain areas. This rain caused one of the largest floods in the history of Los Angeles, Orange and Riverside counties.

All told, the two Pacific storms generated a year’s worth of precipitation in a few days. These events spurred the lining with concrete of the Los Angeles River and other local waterways for flood control.

Lessons from history

“What can we learn from this? The 1937-38 season had a dry start, but in February and March it made history. Meteorology can swamp you with statistics,” Patzert said, “but it’s the unexpected events that can bite you in the butt.”

A dry autumn statistically points to a high probability of a dry season. Patzert cites some other statistics: In the 143-year record, average rain years are rare, and six out of 10 years are below average. There have been only seven years with rainfall over 30 inches, or about twice average. The driest year in L.A. was 2007, and the wettest was 1884. And five of the 10 driest years have occurred since 2002.

“On the one hand, be careful with those statistics. Remember the surprise winter deluge of 1938. The Los Angeles Basin got as much rain in five days as we normally receive in an entire season,” Patzert said. “On the other hand, many climate signals do point to continued dryness in the West.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.