Her COVID-19 treatment cost more than $1 million. Who’s going to pay for it?

- Share via

VACAVILLE, Calif. — It was bad enough that Patricia Mason’s husband rushed her to the emergency room on his birthday and didn’t see her again for nearly a month.

That she was transferred in the middle of the night to a different hospital, one that could better care for her deteriorating condition, and that her husband had no idea where she was or even how to find her.

That her doctor called him two days later to break the news. His wife, the physician said, had less than a 30% chance of surviving COVID-19.

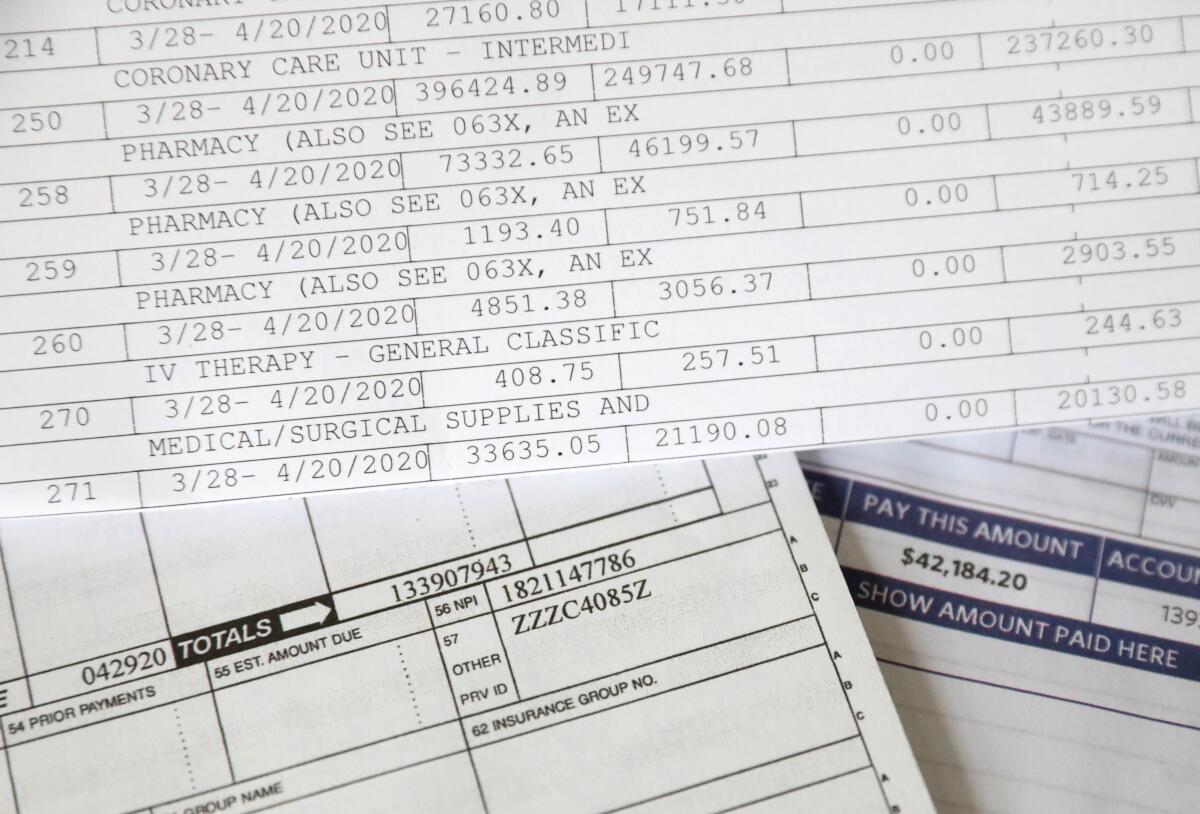

Then the medical bills began to arrive. The grand total to save the 51-year-old woman’s life: $1,339,181.94.

What the Vacaville couple — with five jobs and nine mostly grown children between them — are actually on the hook for: $42,184.20.

The odds that they will pay it off? Zero.

The most serious cases of COVID-19 don’t just attack a patient’s body, leading to pneumonia, respiratory failure, septic shock, blood clots, brain fog and more than 460,000 deaths in the U.S. to date. They can also damage a virus victim’s bank account.

Because, while it is difficult to know who will die from the virus and who will escape with just a runny nose, it is just as hard for patients and the hospitals that care for them to figure out their COVID-19 hit, what is covered and who will actually pay for it.

“The deck is absolutely stacked against the consumer and the patient,” said Sabrina Corlette, co-director of the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University. “The first issue is you’ve got COVID and you’re not feeling so great. Going to battle with the doctors and hospitals or health plan, there’s a huge power imbalance to begin with, let alone when you’re struggling with health issues…. Getting answers about why certain things are on the bill is almost impossible.”

Many insurance companies have waived all out-of-pocket costs for coronavirus treatment, for some patients slashing a million-dollar-plus bill to nothing. But those waivers are entirely voluntary, and many have already expired. Medical bills for uninsured COVID-19 patients are covered by the federal government, but the rules are complex, and hospitals must apply for the money.

During the Obama administration, the federal government capped the amount most insurance plans can require patients to pay. But not all plans have so-called out-of-pocket maximums. And even if they do, the annual limit for a family was $16,300 in 2020, the pandemic’s first painful year. This year, it rose to $17,100, although insurance companies can adopt a lower limit.

Still, not everyone has even that kind of money lying around during the worst recession in nearly a century. Nineteen percent of all adults either lost a job or had their work hours cut in March, and 18% had medical debt even before the pandemic hit, according to a May report from the Federal Reserve.

“I don’t have $42,000 to spare,” Mason said. “We’re at the point where we’re trying to make it through the next 15 years, so hopefully we can one day retire…. I am lucky enough to be alive, so we take that into consideration. But the reality is I don’t have [the money]. It’s not going to happen.”

When the hospital bill arrived, Mason’s husband asked her what they were going to do about it. Maybe pay a dollar a month for the rest of her life, she told him.

::

The first sign that something was amiss came March 22, a Sunday. Mason was dyeing 16-year-old daughter Cheyenne’s hair blue, she thinks. Her husband was cooking dinner.

“Don’t make me much,” she told him. “I don’t feel good.”

That night, she had a fever. The next day, a cold, complete with cough and a hoarse, raspy voice. Five days, two telemedicine visits and two wrong diagnoses later — first the flu, then bronchitis — and Mason announced to her husband and daughter that she had to go to the emergency room.

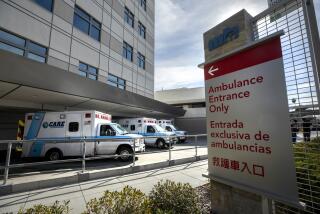

They raced to NorthBay VacaValley Hospital, a mile from their home in this Central Valley suburb between San Francisco and Sacramento. Mason walked in alone; it was March 27, the pandemic’s early days, but family members had already been banned from the hospital.

She texted around midnight that she was being transferred to a hospital in Fairfield, only she didn’t know which one. She told her husband to go home and sanitize the house. She said she’d text again when she arrived at the new hospital. Then radio silence until the next day.

Around 6 a.m. on Monday, March 30, her doctor called her husband with bad news. If the oxygen level in her blood didn’t improve, he said, Mason would have to go on a ventilator. He’d keep her family posted. Fifteen minutes later, he called back. Mason was fighting to survive. It was time to intubate.

“So, I’m like, ‘What you’re trying to tell me, Doc, is she may pass?’” her husband recounted. “He’s like, ‘We don’t know. We’re going to do all we can to help her get better, but we don’t know what the outcome is going to be, what type of treatment we’ll have to give her.’”

The explanation of benefits from her insurer holds some — but not all — of the answers about her hospital stay, which began March 28 and ended April 20.

Her stay in the coronary care unit at NorthBay Medical Center in Fairfield: $479,162.40.

Pharmacy charges: $470,950.94.

Respiratory services: $166,669.80.

The explanation of benefits is dated July 14. The letter from Medical Financial Solutions, a debt collection company, arrived a little more than two months later.

It says, in bright red letters, “Past Due.”

It says she owes $42,184.20.

It says she is “not currently in default but it is very important that we hear from you.”

Mason tucked it into the bulky manila envelope that holds other paperwork from her battle with COVID-19.

::

More than 10 months have passed since Mason walked into the emergency room. That manila envelope is on her dining room table, obscured by a pile of bills and insurance statements. She has survived COVID-19, but it’s not entirely done with her yet.

She has brain fog. Her joints are swollen and painful. She takes a baby aspirin every day, along with a handful of supplements, “anything that I’ve heard will help.” She calls it her “anti-COVID stuff.” New aches or pains cause a twinge of fear.

“Every time I turn around, is this something that’s related to COVID and is it something that’s going to last forever?” she asks. “And nobody knows.”

Mason is insured through her husband’s union. He is an instrumentation technician at a pharmaceutical company. He also unloads trucks at a nearby Lowe’s home improvement store. He does not want his first name used because of the stigma associated with the coronavirus.

The insurance covered Mason’s acupuncture and hernia operations and her daughter’s emergency room visit with low deductibles and very few co-pays. But a serious case of COVID-19 doesn’t play by the same economic rules.

The Masons’ insurance plan is administered by Blue Shield of California, but it’s what is known as a self-funded plan, which means the Southern California Pipe Trades Health & Welfare Fund collects premiums and pays for its members’ care, most generously at hospitals and physicians who are part of its network.

But whereas most health plans are required to follow the federal government’s out-of-pocket maximums, the pipe trades’ plan is “grandfathered in” and does not have to offer all of the same protections. Mason’s insurance does not have an out-of-pocket limit.

Many insurance companies announced early in the pandemic that they would waive all out-of-pocket costs for their members’ COVID-19 treatment.

The Blue Cross Blue Shield Assn., a network of 36 carriers, plans to waive treatment costs for its members through May. Blue Shield of California will waive such co-pays through February. Cigna’s waivers are scheduled to end Feb. 15, according to America’s Health Insurance Plans, an industry trade group also known as AHIP.

Most waivers do not include self-funded plans, such as Mason’s, which are also known as employer-funded plans. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that 61% of Americans who get their insurance through their jobs are covered by these kinds of self-funded plans.

And of the nearly 150 medical insurers listed on the AHIP website, 46% either never waived treatment costs or the waivers have already ended as of Wednesday — even though the pandemic shows no sign of abating any time soon.

AHIP did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

“We’ve been very frustrated by the haphazard nature of the cost-sharing waivers,” said Molly Smith, group vice president for policy at the American Hospital Assn. “The confusing nature of health insurance coverage predates COVID-19, but it has been rapidly and disturbingly highlighted by the pandemic.”

Though Mason’s insurance pays for a generous 95% of a patient’s stay at an in-network hospital, for really sick people like her, the 5% that she is required to pay is a killer.

Take the $166,669.80 the hospital charged Mason for respiratory services. Health plans negotiate with network providers to pay a lower amount than what is charged. In this case, the “eligible expense” was $105,001.97.

The insurance plan paid the hospital 95% of that, or $99,751.87. Mason is responsible for 5%, or $5,250.10.

All of those 5% charges added up to a whopping bill.

::

Natalhie Herrera, who is insured by Cigna, had a vastly different experience when it came time to pay for her COVID-19 medical care.

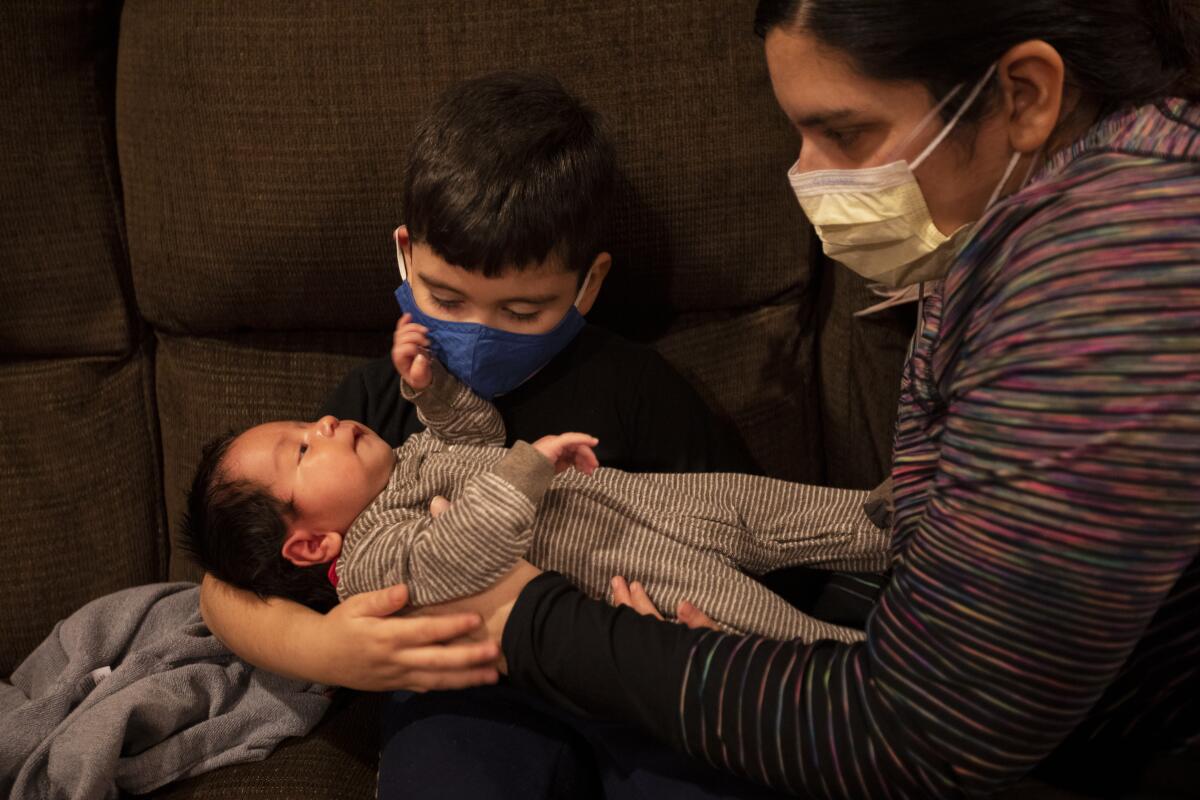

The 35-year-old was admitted to Henry Mayo Newhall Hospital on Nov. 9, unable to breathe. She was 37 weeks pregnant and failing fast.

Felipe was born Nov. 11 by emergency caesarean section and whisked off to the neonatal intensive care unit. Not because he had COVID-19, but because Herrera did. She kissed him on the top of his head and did not see him again for more than a month.

Nearly a week later, she was transferred to Providence St. John’s Health Center in Santa Monica, a hospital with an ECMO machine and a bed available when Herrera needed it. ECMO stands for extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. It is an expensive, last-ditch therapy to save a patient who is on a ventilator receiving the maximum level of oxygen and still dying.

In the living room of the Baldwin Park home where she lives with her husband, her in-laws and her two little boys, Herrera moved her dark hair aside, revealing an angry red scar on her neck where a thin tube called a cannula was placed. She has a corresponding scar near her groin for the other end of the tube.

The ECMO machine pumped her blood out of her body through one end of the cannula, oxygenated it, removed the carbon dioxide and pumped it back via the tube’s other end, bypassing her damaged lungs and allowing them to heal.

“If she would have stayed at Henry Mayo, she would have died,” said Dr. Terese Hammond, director of the St. John’s ECMO program and the physician who treated Herrera. “We’ve done 37 COVID ECMO cases in 2020, and 14 people are alive. … [38%] survival. That’s better than zero.

“Here she is, post-miraculous recovery,” Hammond said, “and she has to sort out these bills and will probably be stuck with thousands of dollars in charges.”

Herrera figures her family will hit their $12,000 out-of-pocket maximum, but those charges are for her delivery and Felipe’s time in the NICU. Fortunately, Cigna waived her COVID charges.

She fired up her laptop, went to the Cigna portal and entered the dates of her COVID-related care.

Claims filed: 139.

Amount billed: $1,344,383.99.

Patient responsibility: $810.39.

Since that late January afternoon, those numbers have crept up a bit. And on Saturday, a mystery medical bill arrived in the mail. There is no date of service, but it appears to be from an emergency room visit at the beginning of her illness.

“Final notice,” it says in big red letters. If she does not pay $1,355.87, her “account will become delinquent in 30 days.”

Because Mason’s self-funded plan did not waive out-of-pocket costs for COVID-19 treatment, her brush with death came with a large dose of sticker shock, unlike Herrera’s.

When she was diagnosed with the virus, hospital bills were the last things on her mind. Especially, she said, because she’d heard that insurance companies were going to waive fees “to make sure people weren’t slammed with bills.”

Mason is the first to acknowledge that 2½ weeks in intensive care is an expensive proposition. But she figured she’d have to pay $5,000 or so.

Then she opened the hospital bill.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.