- Share via

It was a movie-worthy meeting. She was stranded at Union Station, penniless and homeless for the first time in her life. He had a tent outside and came in to get out of the cold.

“He was like, ‘Are you OK?’” Valerie Zeller, 52, recalled. “I was like, ‘Leave me alone.’”

“He was like, ‘Do you need someplace to stay?’ I was just kind of speechless. I was like, ‘Yeah.’ He was like, ‘I won’t try to do nothing.’ I said, ‘Yeah, OK. Why not?’”

That night last September she slept in his tent while he sat outside. It was only a few weeks before she knew.

“It’s just, you know when you know,” Valerie said in an interview a few days before the wedding. “You just know when that person comes along. Long story short, I asked him to marry me.”

Henry, 63, whose last name Valerie doesn’t know, agreed to become Henry Zeller.

The clouds parted for the wedding Saturday steps away from their tent home near Echo Park Lake. But a more ominous cloud hung over the ceremony as rumors swirled through the lakeside homeless camps that a city sweep to remove them is only days away.

Zeller said she’s gotten mixed signals from police and outreach workers.

A homeless encampment at Echo Park Lake has become a symbolically fraught case study of the rights to public spaces

“They are; they’re not,” she said. She hears “they want to bully people: they don’t want to bully people. Which is it? ‘We’re closing down the park soon.’ Oh, you are? I’ll chain myself to a tree. I ain’t going nowhere.”

Heedless of that uncertain future, Zeller put on her makeup, donned a white gown and veil and, with the help of the wedding retinue from the Wilderness International Church, climbed into an improvised chair on wheels to make the short trip from her tent to the tip of the peninsula where the Lady of the Lake statue stands.

Zeller, who said she suffers extreme pain in her leg from complex regional pain syndrome, also had a black and blue foot from a recent attack with a baseball bat.

“Everybody here hates me because I clean up the park and I’m a girl that has things, nice things,” she explained.

Pastor Billy Roe, whose church conducts outdoor services at the park, said colleagues had urged him not to perform the ceremony because the bride and groom were not stable.

“I was literally very upset,” Roe said. “We all are not stable. They are homeless, as you know. But it doesn’t mean that they don’t have hope. This is the beginning of hope in front of Jesus Christ.”

Their paths to Echo Park were circuitous.

“I lived in Vegas for a long time,” Valerie said. “I was a showgirl. I used to be very pretty. But whatever. No matter.”

She had been in L.A. a couple of decades, most recently living with a friend in Santa Monica when rising rents drove them out. He moved them to an RV in Pomona and she put her things in storage.

“He liked me more than I liked him,” she said. “But when he hit the dog, I said, ‘I’ll be homeless.’”

She and Redd, the dog, got on a bus to Los Angeles. She intended to catch a bus back to Las Vegas but said she lost her phone, ID and money in an altercation with the bus driver over Redd sitting on a passenger seat.

A large homeless encampment on the banks of Echo Park Lake has emerged as a divisive flashpoint in Los Angeles’ crisis of how to treat the unhoused. Now the city is believed to be preparing to sweep the camp and close the surrounding park.

Henry, who declined to give his last name, said he’s of Puerto Rican descent, but grew up around 9th and Alvarado streets. He was alternating between New York, where his father lived, and Los Angeles, where he was taking care of his aging mother. But then his father died and his mother returned to Puerto Rico.

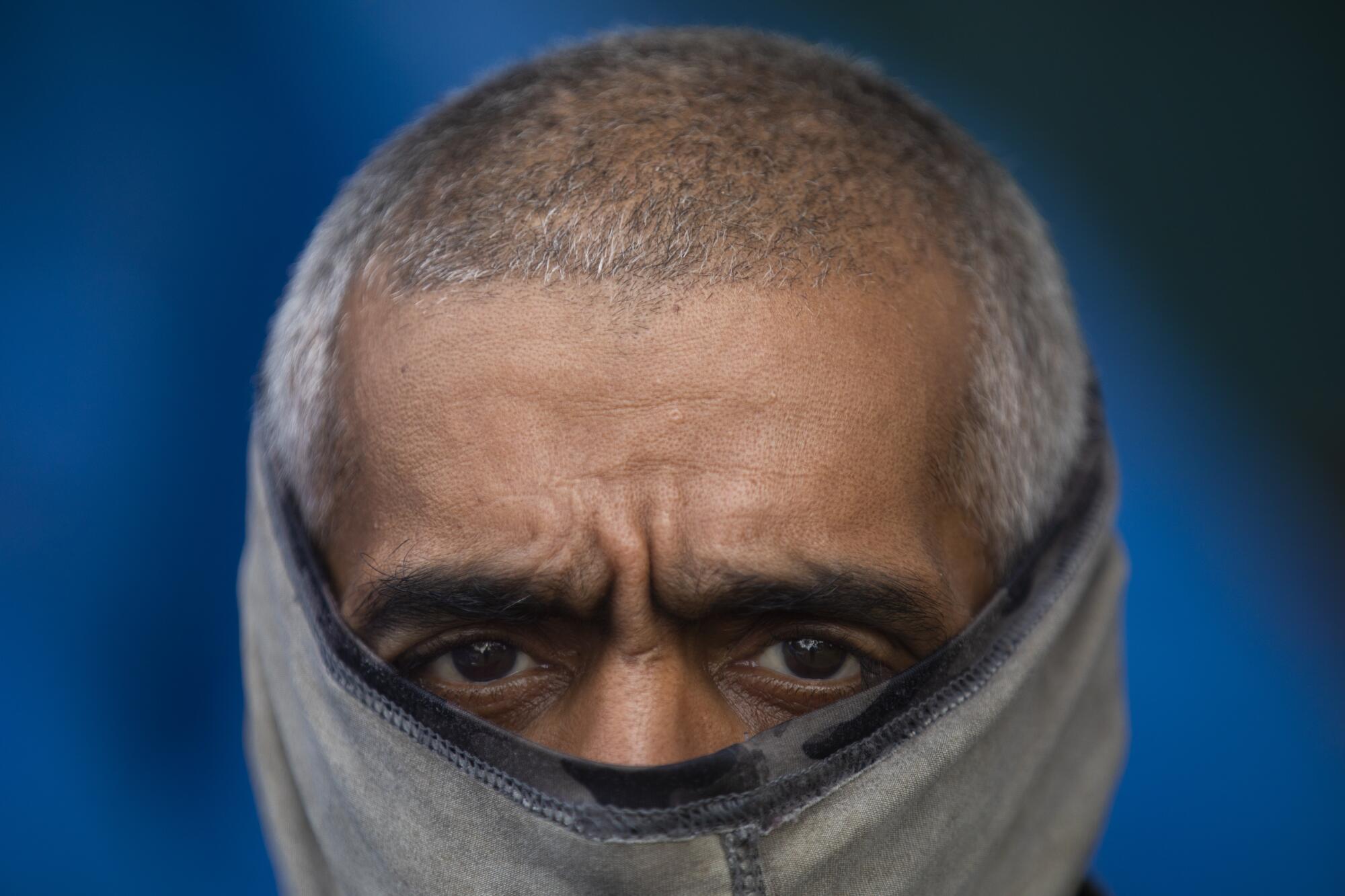

A veteran of the Gulf War, he wore camouflage to the wedding, down to the cap and neck gaiter. There are periods in his life he won’t discuss, but he said he was living with a girlfriend in Santa Monica when his veterans benefits were cut over a clerical error that can’t be corrected during the pandemic.

“Suddenly, she didn’t have anybody to help pay for her car payments,” he said. “It turned into a money thing. That’s when I realized I was with her for the wrong reason to begin with.”

Henry had briefly lived with friends in Echo Park before and returned to what he knew. But it had changed.

“All my friends were gone,” he said. “There were a lot more homeless people.”

He relocated to Union Station and might have stayed until he met Valerie.

“The dog didn’t like it there,” he said. “No grass, no place to play.

“I’m going to take you to a place where at least the resources will come to you,” he told her. “You’ll get food, access to clothes. We can get a sizable tent, a tent for our storage. She fell in love with this place.”

“It’s so funny, that I’m homeless and I’ve never been happier in my life,” Valerie said.

With added tents for clothes and furniture that came out of storage and a neighbor whose tent abuts theirs, they now have the largest spread among nearly 200 tents that have sprouted up in the park.

After exchanging their vows, Valerie walked on her own at Henry’s side to the reception on a grassy area near their tents.

They took their place at a decorous folding table as the guests lined up for Korean barbecue.

There would be no honeymoon, Valerie said.

“They offered us a hotel, but we couldn’t accept,” she said. “I was afraid to go because some people in the park would take everything we have if we leave.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.