A mobile clinic brings vaccine to California’s city of essential workers

- Share via

The guilt gnawed at Gabriela Alvarez after she infected her mother and three children with COVID-19 in August.

“I felt so bad, because I brought this virus to my house,” the 33-year-old said. “I was worried about my mom, because she was older and was afraid she wouldn’t be able to make it.”

Alvarez was determined to get vaccinated when she became eligible in February because she works in food production, at My/Mochi Ice Cream in the city of Vernon. But she had no success getting an appointment until a mobile clinic set up shop in the industrial town. Last week, she got her second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

The mobile clinic was an effort to inoculate the city’s essential workers. And few places have as many as Vernon.

Vernon, in southeast L.A. County, is a town of strange proportions. Only about 200 people live there. But it is home to about 1,800 businesses that employ roughly 55,000 workers.

They work day and night in places like the Farmer John meatpacking plant, recognizable by its bucolic mural depicting cavorting pigs; Tapatío Foods, the maker of the popular Mexican-style hot sauce; and Rose & Shore, a food processing plant that specializes in cooked deli-meat items and prepared foods for schools, airlines and supermarkets.

And when they go home, the essential workers often head to nearby working-class cities where poverty, overcrowded housing and high rates of health issues such as diabetes and heart disease make their population vulnerable to COVID-19.

“Whatever we could do to bring [the vaccinations] to them, to make their life a little less complicated — that was really our focus,” said Frederick Agyin, Vernon’s director of Health and Environmental Control. “It’s a small token of appreciation for everything they’ve done and what they’ve been going through.”

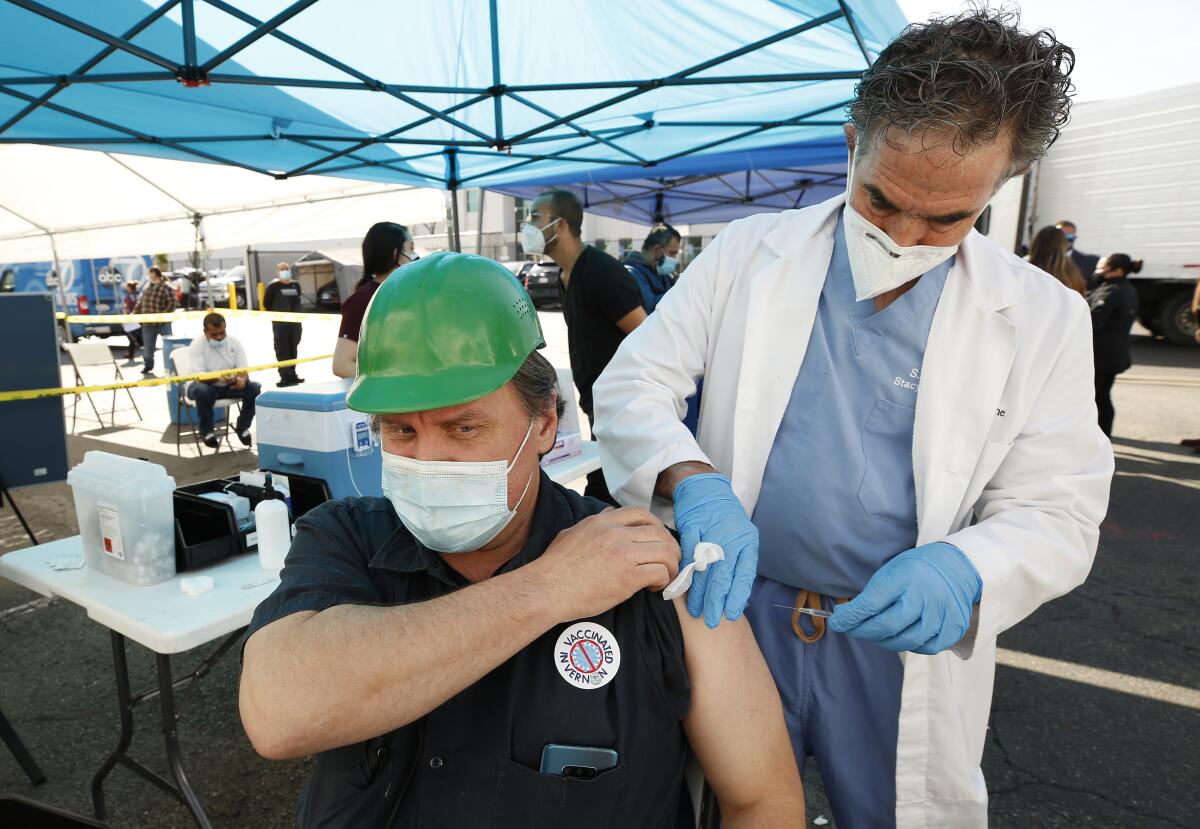

“They didn’t have the luxury of social distancing like other companies or to stay home,” added Dr. Steven H. Florman, founder of the Stacy Medical Center in Vernon, with which the city contracts to provide medical services to its industrial workers.

Vernon’s mobile vaccination program travels to work sites, in some cases targeting companies that saw large coronavirus outbreaks, including Farmer John and Rose & Shore. It boosts access for people who not only work irregular hours but may have a difficult time maneuvering L.A. County’s vaccine website.

“We thought it was critical we be on-site,” Agyin said, adding that more workers may want to get vaccinated when they see colleagues doing it. “We’re kind of seeing that as we go.”

Before the state expanded vaccine eligibility, Vernon health officials were focused on vaccinating workers in the food and agricultural sector — about 11,000 people.

As of this week, according to the city’s records, they have vaccinated more than 5,000 such workers. Agyin said once they hit 11,000, they will expand the program to everyone else, including the city’s famously few residents.

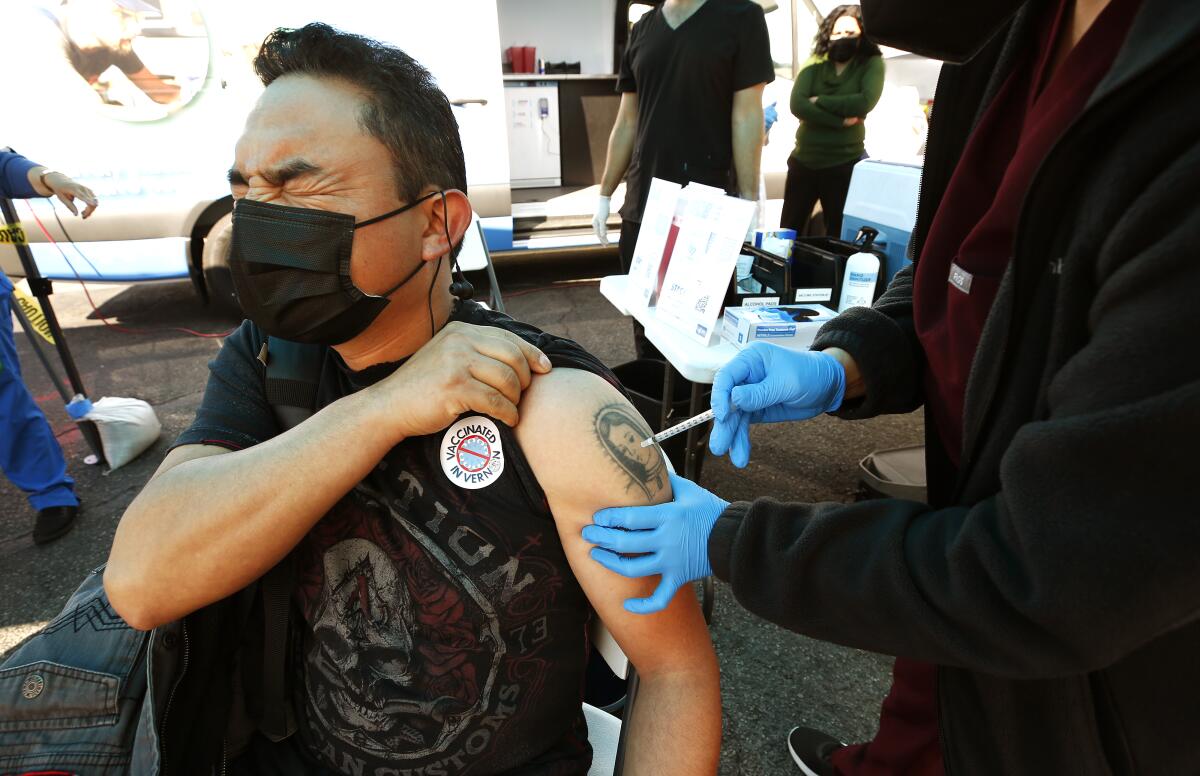

On a recent Tuesday morning, the mobile clinic set out to provide a second dose of Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine to 268 workers at three food processing plants, starting with My/Mochi Ice Cream, the largest U.S. seller of the Japanese dessert.

The blue Mercedes Sprinter van rolled into the parking lot, and healthcare workers began to give shots to employees. A monitoring area was set up near the van, with chairs placed six feet apart.

Julia Majera, 52, who works in the ice cream company’s packaging department, said she had long waited for the day she’d be vaccinated. She had been feeling anxious all year about whether she’d be able to get a shot, given the high demand.

Majera said she is diabetic, and her 47-year-old husband has undergone heart surgery. She knew they were at high risk if they contracted COVID-19.

“I feel blessed and so grateful that the company helped organize this,” she said. “I was worried for myself and for my husband.”

A wave of relief washed over her as she received her second dose of the vaccine.

“I’m protecting myself and everyone around me,” Majera said. “I’m happy to see my colleagues are getting vaccinated too.”

Russell Barnett, managing director and chief marketing officer of My/Mochi Ice Cream, said the company wanted to vaccinate its employees the moment they were eligible.

“We want to keep them safe and their families safe,” he said. “And, on the food-safety side, obviously we’re an essential workforce, and we want to make sure that our food and the food we get to the rest of the world or the country is safe as well.”

Vernon officials say the program has been a successful collaboration between the city’s health department, the Stacy Medical Center, L.A. County Supervisor Hilda Solis and the resident businesses.

“People are happy to get the vaccine without having to go online to register and make an appointment, because some people were having difficulty with that,” said Vernon Mayor Leticia Lopez. “In addition, they’re not having to take the day off from work to get the vaccine.”

The vaccination effort is a good look for a place that for generations operated more like a secretive fiefdom than a city. Years of scandal and corruption nearly caused Vernon to be disincorporated out of existence in 2011. Its small population — which at one point numbered about half the current one — was largely made up of people connected or indebted to City Hall for employment.

Vernon officials avoided disincorporation by agreeing to reforms and $60 million in community projects.

Carlos Fandino Jr., the city administrator, said Vernon has enacted more than 150 reforms, ranging from term limits for council members to salary caps for department heads. Additionally, the city is looking to increase its population to about 2,000.

He said Vernon parted ways with its fire department by contracting fire services to Los Angeles County, a move that would not have occurred under past city leaders who cultivated an insular culture.

“We recognize our community needs to evolve,” Fandino said.

Challenges remain. The city’s environmental impact on its neighbors is an issue that continues to be discussed. Vernon’s Exide Technologies battery recycling plant was shut down in 2015 after years of spewing arsenic and lead into other southeast L.A. locations, including Huntington Park, Boyle Heights and Maywood.

Fandino said Vernon is trying to be a good neighbor. It contributed $250,000 from its community development fund to support free COVID-19 testing in the area by medical provider AltaMed.

Meanwhile, it is looking to boost its vaccination drive by purchasing a second van to increase the amount of territory it covers, Fandino said.

Last year, the city partnered with USC’s Keck School of Medicine to conduct test trials for the vaccine by U.K.-based pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca. Three trailers were installed in the back of Vernon City Hall; one had a freezer to hold the vaccine vials.

But the trials were placed on hold. In December, amid another surge that was devastating for Vernon businesses, Agyin and Florman began to discuss how they could get workers vaccinated.

Envisioning a mobile clinic, the city purchased the $100,000 Mercedes Sprinter van, later customizing it so that healthcare workers could prepare the vaccines at job sites. The van became operational Feb. 26, distributing vaccine first to people 65 and older.

On March 15, the van was used to vaccinate about 546 workers at the Farmer John meatpacking plant, which employs 1,800 in total. Soon after, it was used to vaccinate 250 essential workers at Rose & Shore.

Last week, the van made stops at Broadleaf Venison USA, which distributes specialty meats, and F. Gaviña & Sons, a coffee distributor.

Among those who were vaccinated at Broadleaf was Patricia Deloa, 48, of South L.A., who works in the packaging department.

Deloa said she worried about infecting her grandchildren, whom she cares for after work.

She said her daughter got sick in December and infected the family. They all recovered.

Deloa was excited when she learned that the mobile clinic was coming to her workplace. She said her grandson was afraid she would get sick after being vaccinated because of what he had seen circulating on social media. But Deloa was undaunted. She said she wanted her grandchildren to know why she was doing this.

“I did this for them.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.