How sewing masks for the vulnerable stitched together an empowering Facebook community

- Share via

Let me tell you from the get-go that the creator of one of the nation’s largest and most diverse grass-roots mask-making efforts did not intend to start a movement, to mobilize the masses, to spend the last year searching out under-resourced communities and commandeering fabric and elastic to give away thousands of COVID-19 face masks.

A year ago March, before she launched a Facebook group called the Auntie Sewing Squad, performance artist and comedian Kristina Wong was like so many of the rest of us at the start of the pandemic. “Grief. Uncertainty. Panic. Anxiety. Doom. Anyone else?” she posted on Facebook.

Suddenly, she was a shut-in, stuck in her Koreatown apartment, watching her life as she’d planned it implode. She’d been about to tour her latest show. But date after date canceled, leaving her out $7,000. In live videos, she mused that this might be a time to clean the house, organize computer files, “turn inward.” But that isn’t what she did.

Wong turned outward. She offered help to others.

This is a story about how help, once offered, often sparks more help in unexpected ways.

From the beginning of the pandemic, Wong, 42, was conscious of her privilege. She had savings. She had a home and — a self-proclaimed hoarder — ample supplies. She didn’t see government stepping up for those who didn’t.

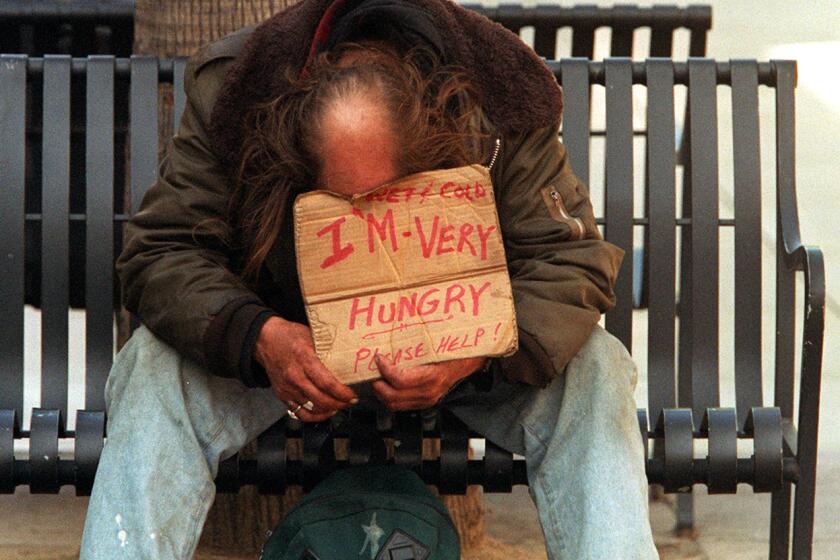

As a representative on her neighborhood council, Wong successfully lobbied for a portable toilet and hand-washing station for people living on nearby sidewalks. She brought them tents, quarters for laundry, Tide Pods, socks from her own drawers.

She also had some fabric and some elastic and a Hello Kitty sewing machine, which she used to make sets and props for her shows. So she found a pattern online and made a mask.

And then she took a fateful step that didn’t seem like one at the time: She offered on social media, “if you don’t mind really messy stitching,” to make masks for anyone in need.

Within days, she’d been bombarded with asks well beyond what she could fulfill.

In search of helpers, she created the Auntie Sewing Squad, which just celebrated its first anniversary — more than 800 volunteers strong nationwide. Among the aunties, who have ranged in age from 8 to 93, are artists, professors, teachers, homemakers, health professionals, screenwriters.

And in one year, the aunties (and, as Auntie Laura Karlin told me, the uncles and the cousins and the unties — the mostly female squad welcomes all genders) have made and donated more than 300,000 masks to many of the most vulnerable among us.

They have made masks for poor communities of color and masks for those who lack housing. They’ve made masks for people in jail, sex workers, farmworkers, Native Americans living on reservations, migrants seeking asylum at the border. After George Floyd’s death last May, they sent masks for distribution to NAACP offices in Minneapolis and other cities where police have killed unarmed Black people, as well as to groups on the ground at Black Lives Matter protests, to be handed out to protect protesters.

As they’ve sewn, they’ve chatted online with one another openly, humorously, sometimes profanely, about their political views. This is not a neutral crew. After a shooter killed six women of Asian descent at spas in Atlanta last month, the group had a vigorous online discussion and then issued a statement condemning “rising anti-Asian hate and violence.”

They learned fast that connecting and sharing mattered more than having a budget. What good did cash do, after all, in those early days when basics were nowhere to be found and aunties were cutting up bra straps and fitted bedsheets for elastic? Still, they have gotten a lot of publicity and received donations into the six figures — and they have used those funds not only for mask-making supplies and postage but also to help meet the broader needs of the community groups and organizers they’ve connected with.

The other day, I spoke to Theresa Hatathlie-Delmar, who grew up in the Navajo Nation and is an organizer for a group called Navajo & Hopi Families COVID-19 Relief. Wong contacted her last summer, and the aunties have since sent her five vanloads of supplies — not just giant rolls of fabric and thread and sewing machines for her people’s own mask-making efforts but 3-D printers to make face shields, diapers, detergent and so much more.

“There’s this goal to serve people but also to share power, even to help others empower themselves,” Hatathlie-Delmar said of the aunties.

Central to the Auntie Sewing Squad is this ethic of mutual aid. They stepped in to fill a void left by the government’s failures, Wong said, and ended up acting as a “shadow FEMA.” And they’ve learned a lot in the last year about how much is required to do such work effectively and respectfully.

Do you know someone in Los Angeles who does great good for others? This columnist is looking to talk to people about how they started helping and what they’ve learned from experience.

Before she created her Facebook group, 20 of Wong’s first masks went out to the New York City firehouse of Sarinya Srisakul, a fan of Wong’s shows who in 2005 became that city’s first female Asian American firefighter. But Wong couldn’t meet other, equally worthy requests.

“I was thinking, what have I done? This is Sisyphean,” she recalled. “I was already having to play God every day, thinking who’s going to get this next mask. It’s not going to be the out-of-work dog walker who’s an actor. But who should it be? These nurses? Those nurses?”

The name she’d chosen for the group, she said, was meant to convey a casual coming together to help fix what she felt sure would be a short-term problem.

At first, she reached out for help to friends she knew were already sewing. Most, like her, were Asian American. Some, like Wong, who grew up in San Francisco, had family members who had worked in the garment industry. Her paternal grandparents had run a laundry that did alterations. It wasn’t lost on her that their college-educated granddaughter was now doing the same work they’d done to survive, to help others survive.

Here she was, asking people to turn their living rooms into sweatshops. She began to call herself the group’s “Sweatshop Overlord,” a tongue-in-cheek title that stuck. But the group took its unpaid labor seriously. Aunties wanted their work to be of value.

So as the number of aunties quickly grew and inexpensive masks became available to buy, the squad determined to shift its mask production away from the front-line workers at places with big budgets to purchase masks, such as hospitals, to historically underserved communities hard hit by the pandemic and lacking the resources to adequately protect themselves.

“All these people were finding us on Instagram and Facebook. But we thought, there have to be communities all over the country where people don’t have those access tools,” Wong said. “How do we find those people?”

A small group of “Super Aunties” began searching out and forming relationships with community groups and organizers all over the country. The group began asking those requesting masks to be very specific — about what their circumstances were, whom the masks would be going to, how they would be distributed, exactly how many were needed. In the Facebook group, aunties receive notices of the various campaigns and decide which ones they want to help fulfill. They then pledge the number of masks they will produce — and Super Aunties keep track of it all.

Karlin recently ran a 2,000-mask campaign for six organizations supporting farmworkers that was fulfilled in a matter of hours. That’s how nimble the network is now.

A man with a PhD lost his six-figure job and became homeless. He asked strangers to foster his dog. When his story was told, help poured in and gave him what he needed to get back on his feet.

Karlin does her work for the squad while also serving as founding artistic director of Culver City’s Invertigo Dance Theatre and caring for her 16-month-old daughter, Juniper (known as LB, or Lazy Baby, in the group, as in, why isn’t that lazy baby sewing masks?). Which brings me to another key element of the Auntie Sewing Squad: care. The aunties’ mission isn’t intended to add to their pandemic stress.

Not all aunties sew. Some are Care Aunties, who offer support in the form of care packages, Zoom yoga classes, anything to make their fellow aunties feel appreciated. Many aunties send one another spontaneous gifts. Karlin sends out homemade hand salve.

I’ve spoken to a lot of aunties in recent days. Most have stressed how much the aunties’ mutual care has helped them muddle through the pandemic.

Kats Mendoza, who lives in Iowa City and who has made more than 2,000 masks for the group, came to Iowa from the Philippines in her 20s for graduate school and stayed. One of her fellow aunties, she said, sent her Japanese bubblegum that she used to buy at her corner store back home. “Where I live is a predominantly white community, and it’s been really lovely to become part of this group with so many women of color, immigrants, the children of immigrants,” she told me.

Grace Yoo, a professor of Asian American studies at San Francisco State University, told me that she learned to sew to make masks, and after joining the aunties, started a group to get her students sewing. Among the aunties, because of Wong, there’s “lots of laughter because she’s hilarious,” Yoo said. “We kind of needed some comedy to counter the extreme terror.”

Sunni Won, 59, who came to L.A. from South Korea when she was 10, has been making masks for the aunties’ campaigns with her mother, Myong, 83. New in America, her mother did piecework and then ran a sewing factory. She ended up a Disney costume maker. The pandemic was wearing on her mother, Sunni said. Dementia was setting in. She was blue about not being able to travel.

Now Sunni cuts the mask shapes and mails out the finished masks. Her mother works the sewing machine. Together, mother and daughter have produced about 2,500 masks. “It gives her something to do, a purpose,” Sunni said of her mother, who’s at it eight hours a day.

At Sunni’s request, aunties from all over the country have sent Myong postcards to soothe her travel bug. She carries them around and loves looking through them.

A group of strangers came together virtually to make masks, but in the end they made so much more.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.