California’s secret weapon in COVID-19 success: We are not skeptical about the vaccine

- Share via

A number of factors have fueled California’s remarkable turnaround from national epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic to having one of the lowest case rates in the U.S.

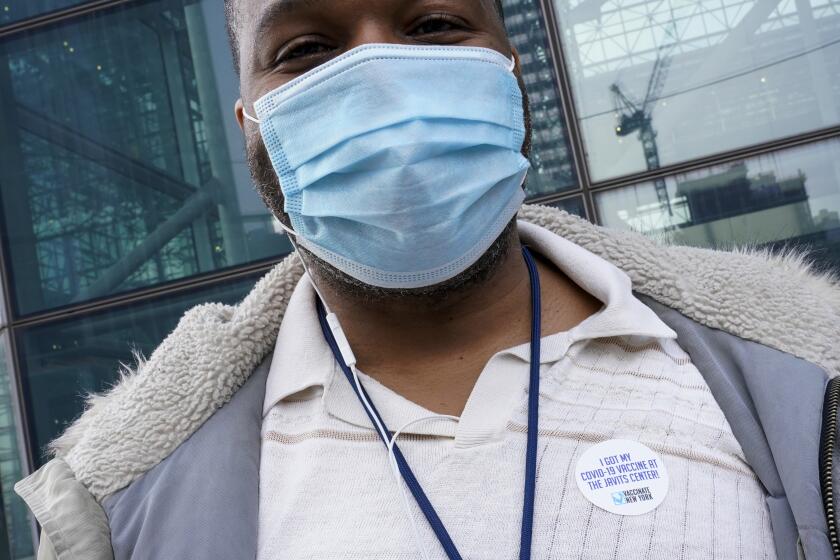

But one weapon in its arsenal has gone largely unnoticed: Californians’ general embrace of COVID-19 vaccines.

Federal data indicate only about 11% of Californians are estimated to be vaccine hesitant, a lower rate than all but four states: Massachusetts, Vermont, Connecticut and Hawaii.

This relative lack of reluctance has undoubtedly been a boon for the state’s inoculation campaign — though a Times analysis shows Californians in some of the state’s conservative rural areas remain more disinclined to get the shots than their urban-dwelling neighbors.

According to estimates from U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which are based on survey data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the seven California counties pegged as being most dubious toward the COVID-19 vaccines are Yuba, Del Norte, Plumas, Modoc, Siskiyou, Lassen and Kings.

The share of those counties’ populations estimated to be vaccine hesitant — meaning they either would probably not or definitely not receive a COVID-19 vaccine when available — ranged from 14% to 16%.

By comparison, the rates in the least hesitant of California’s 58 counties — San Francisco, Marin, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Contra Costa, Orange and Alameda — were between 7% and 9%, federal estimates show.

Officials and experts say there’s no one overriding reason why certain groups or individuals might be more dubious about the doses than others. Some may be skeptical for political reasons or because of deep-rooted distrust in the healthcare systems that have long overlooked or underserved them.

Other people may just be uncomfortable with the seeming speed at which the vaccines were developed.

In Los Angeles County, where an estimated 11% of the population may be vaccine hesitant, Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said she doesn’t think it’s unreasonable that people may be “looking for more information before they make up their minds about when and if to get vaccinated, who want to better understand safety issues and concerns.”

“They want to make sure they understand, ‘Why bother getting vaccinated? What’s the effectiveness of this?’ ” she said during a recent briefing.

There are signs that interest in the vaccine has waned recently in the county. There was a 50% drop in first dose appointments this past week, Ferrer said, and city officials announced Friday that the Dodger Stadium vaccination site — one of the largest in the country — would close by the end of May.

That some people may be more reluctant to get vaccinated isn’t a surprise, officials and experts say. A segment of the population has long been resistant, or outwardly hostile, to all manner of inoculations, and that probably won’t change, even in the face of a pandemic.

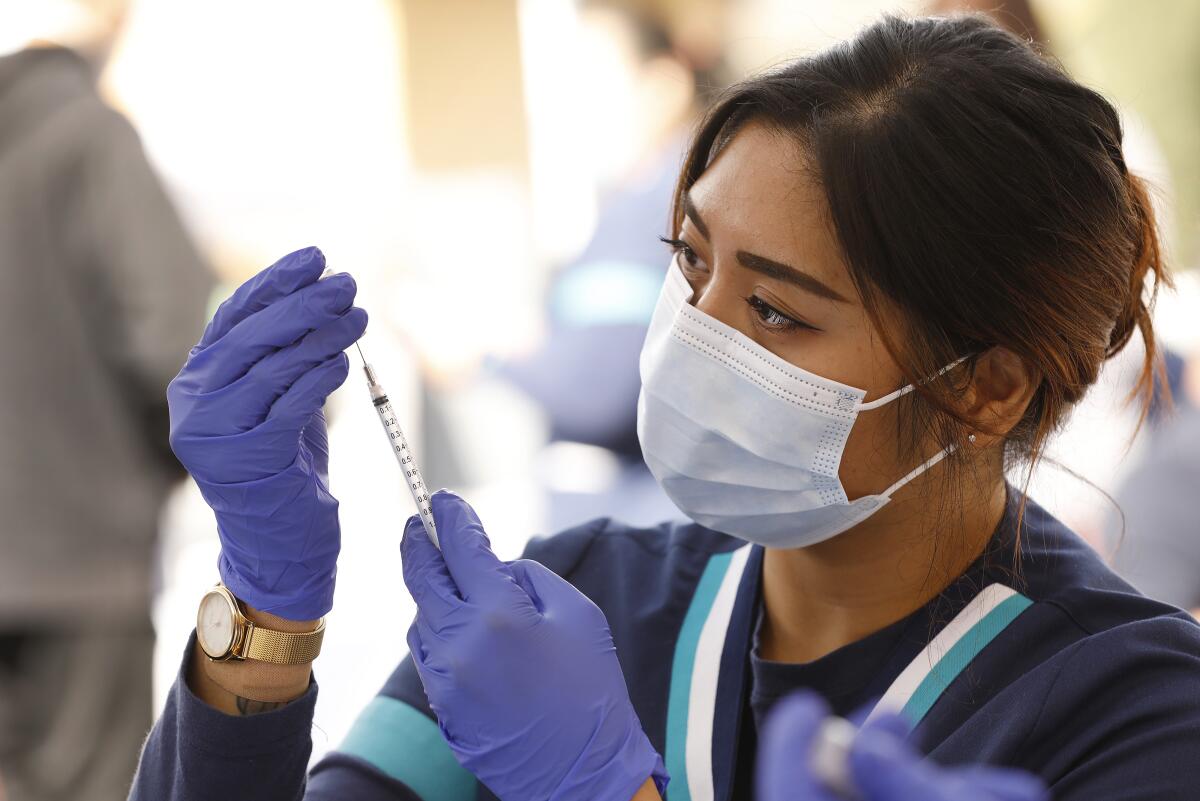

Places around the U.S. are offering incentives to try to energize the nation’s slowing vaccination drive and get Americans to roll up their sleeves.

While it’s doubtful the entire population will ever be fully vaccinated against COVID-19, health experts have said a smaller but still significant share — usually estimated at 80% or higher — is what’s needed to achieve herd immunity, the threshold at which enough people are shielded against transmission that the coronavirus is unlikely to spread.

Too many people refusing to get vaccinated would lengthen California’s trek toward widespread protection. And with the vaccine rollout entering its fifth month, there are concerns that those who were eager to roll up their sleeves may have already been vaccinated, leaving a much harder task ahead: persuading those who are less willing to get a shot.

Even if the state reaches herd immunity, there is a fear that high numbers of vaccine holdouts in particular communities would still give the coronavirus ample opportunities to spread, further prolonging the pandemic.

“We cannot hide behind what the average number is. We have to look at our pockets” where transmission could remain, said Dr. Robert Kim-Farley, a medical epidemiologist and infectious disease expert and a professor at UCLA Fielding of Public Health.

Despite reopening gains, experts think herd immunity is a ways off, and they say several factors will keep COVID-19 a fact of life for some time.

Though officials caution against reading too much into small geographical differences, the estimated hesitancy lists do line up neatly — though not entirely — with county-level vaccine coverage in California.

In Lassen County, for instance, only about 20% of residents have received at least one vaccine dose — easily the lowest rate in the state, according to data compiled by The Times.

Kings County has the third-lowest rate, 25%; Yuba the fourth-lowest, 27%; Modoc the fifth-lowest, 28%; and Del Norte the seventh-lowest, 31%.

Siskiyou and Plumas counties, though faring a bit better, still have one-dose coverage trailing well behind the statewide average.

On the other hand, Alameda, Contra Costa, Santa Clara, San Mateo, San Francisco and Marin counties all rank among the top nine counties statewide in terms of at least partial vaccination — with coverage ranging between 56% and 66%. Orange County is at 47.3%.

Statewide, roughly 46% of Californians have received at least one dose.

Dr. Aaron Kheriaty, director of the medical ethics program at UC Irvine and a member of the vaccine task force in Orange County, said it’s key to recognize “that the population in California is not homogenous — there are cultural, ethnic, moral, religious and medical differences between various individuals” and to hone “a public health strategy that thinks through that diversity.”

Among those Californians who have opted not to risk taking a vaccine is Mary Maguire, 59. The West Los Angeles resident said she has a history of allergic reactions to vaccines. Even so, the decision has caused her anxiety amid growing pressure to get a shot.

“We know that the vaccine is not 100% safe and that some people will experience issues even if it’s a small percentage. It’s fine to write that off as not a big deal, until you become the person who has the issue,” Maguire said. “I believe the science — I’m not an anti-vaxxer — and if I didn’t have this history I would probably have gotten it by now. Many of us have legitimate concerns.”

People with developmental disabilities practice taking shots to avoid anxiety, and potential physical resistance, when time arrives to take the COVID-19 vaccine.

Terre Dunivant, 62, a graphic designer from San Luis Obispo, said she has no political objection to the vaccine. Rather, she worries about whether the potential effects on people with autoimmune disorders have been fully studied.

“I don’t believe that they have figured out how to handle people who have the issues that I have,” said Dunivant, who suffers from multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. “It’s just this rush to get everything out there.”

First-dose appointments decreased by about 50%, which could mean that the county will not reach its goal of administering 95% of its supply over a seven-day period.

While the federal estimates indicate that only a relative sliver of Californians may balk at getting vaccinated, other polling data have found a far higher level of resistance.

In a statewide survey published in March by the Public Policy Institute of California, 21% of adult respondents said they would either probably not or definitely not get the vaccine.

Among those with the highest hesitancy rate were registered Republicans, 39% of whom said they would probably not or definitely not get vaccinated.

That opinion was shared by 19% of independents and only 10% of registered Democrats.

All seven California counties with the highest estimated rates of hesitancy went for Donald Trump in the 2020 presidential election.

In that same PPIC poll, about 29% of Black Californians said they would either probably not or definitely not get the vaccine, down from 55% in January. Among Latinos, 22% were hesitant, a rate that was unchanged from the previous two months.

That viewpoint was shared by 20% of whites and 5% of Asian American residents.

Hesitancy in the Black community has in part been attributed to historic mistrust in the healthcare system after racial disparities in access and events like the U.S. government’s notorious Tuskegee experiment — in which doctors for decades used Black men as unwitting test subjects, withholding treatment for syphilis long after a cure had been found.

Among those surveyed nationwide by the Census Bureau as of March 29, 15.6% said they were hesitant about receiving a COVID-19 vaccine. Of those, nearly half said the reason was that they were concerned about potential side effects, and almost 39% said they planned to wait and see whether the shots are safe.

However, 36.1% said they didn’t trust the vaccines, 28.6% said they didn’t trust the government, 27.6% said they didn’t believe they need it, and 20.3% said they didn’t know whether the vaccines would work.

U.S. health officials see two kinds of people: Those who are vaccinated and those who aren’t. They’re trying to get unvaccinated Americans to switch sides.

Looking ahead, health officials say it’s vital to tear down any potential barriers to vaccine access so that those who have been on the fence don’t run into any roadblocks when they decide to get off it.

California has worked with community outreach groups to educate residents via trusted sources about the vaccine and launched media campaigns in various languages in an attempt to connect with those who may be unsure about getting a shot.

Times staff writer Rong-Gong Lin II contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.