- Share via

There have been such joyful days lately, when the COVID-19 vaccine clinics that Payal Sawhney helps organize at a Hindu temple in Norwalk are bustling, with thousands of people getting shots.

And there have been days when about every phone call and WhatsApp message brings news of yet another friend or relative sick or dead in India.

For the record:

3:03 p.m. May 16, 2021An earlier version of this article said Payal Sawhney’s mother-in-law had tested positive for the coronavirus. She was exposed but did not test positive.

Sawhney’s mother, in the southern Indian city of Hyderabad, has COVID-19. Her brother does, too.

In the city of Gurugram, near New Delhi, her husband’s aunt and uncle tested positive for the coronavirus, as did their son and daughter-in-law, and their two children.

“It feels like, being immigrants between two countries, we are on a roller coaster ride, up and down, up and down,” said Sawhney, 44, of Cerritos.

“When it was bad in L.A., it was good in India. We were at peace, at least, knowing our families back home were OK. Now, it’s getting good here and bad there. It’s just a cycle. It’s not ending for us.”

The homeland is overwhelmed with COVID-19, and many Indian Americans in California, home to more than 500,000 Indian-born residents — more than any other state in the U.S. — teeter between hope and despair. They cheer plummeting coronavirus cases and deaths and enjoy loosened pandemic restrictions here, even as they anxiously check on loved ones in India as it faces one of the worst outbreaks in the world.

The outbreak is emotionally disorienting for Indian Americans in Southern California, which dramatically recovered from a winter surge that overwhelmed the healthcare system, with inundated hospitals turning away ambulances and placing patients in hallways and gift shops.

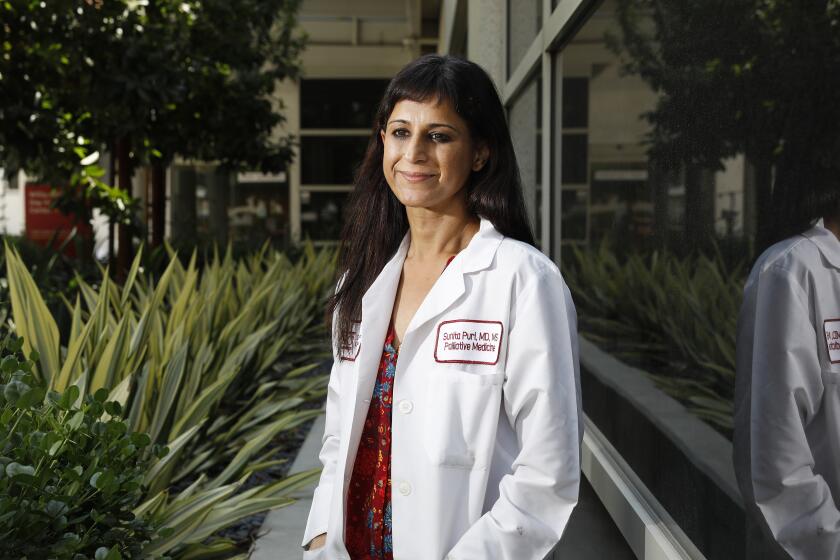

The dire COVID-19 situation in India has been particularly hard to watch for many Indian American healthcare workers.

Earlier this year, Charuta Gondhalekar’s family in India checked on her often as cases surged in California. The situation is reversed now.

Her brother-in-law, who lives in the United Kingdom, recently tested positive for COVID-19 after visiting family in Pune, a city of some 4 million people in west India, where his father died of the disease.

“I’m scared to check the phone in the mornings,” said Gondhalekar, a 36-year-old software engineer who lives in northwest Orange County.

And yet, at a vaccination clinic last weekend at Sanatan Dharma Temple in Norwalk, she was hopeful. She had just gotten her second Moderna shot. The relief, coupled with her fear for loved ones in India, feels like “going in circles,” she said.

“When it was bad in L.A., it was good in India. We were at peace, at least, knowing our families back home were OK. Now, it’s getting good here and bad there. It’s just a cycle. It’s not ending for us.”

— Payal Sawhney

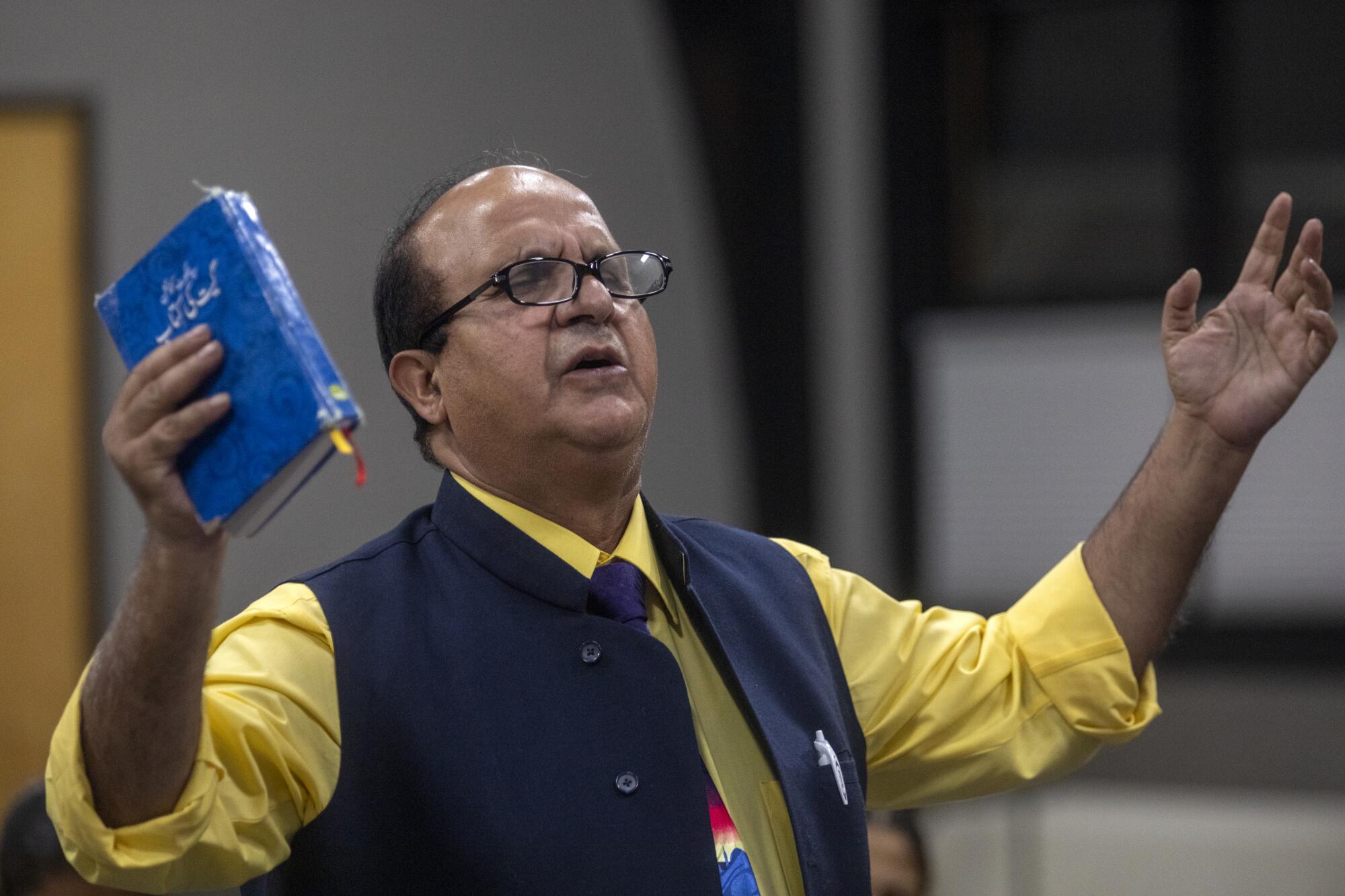

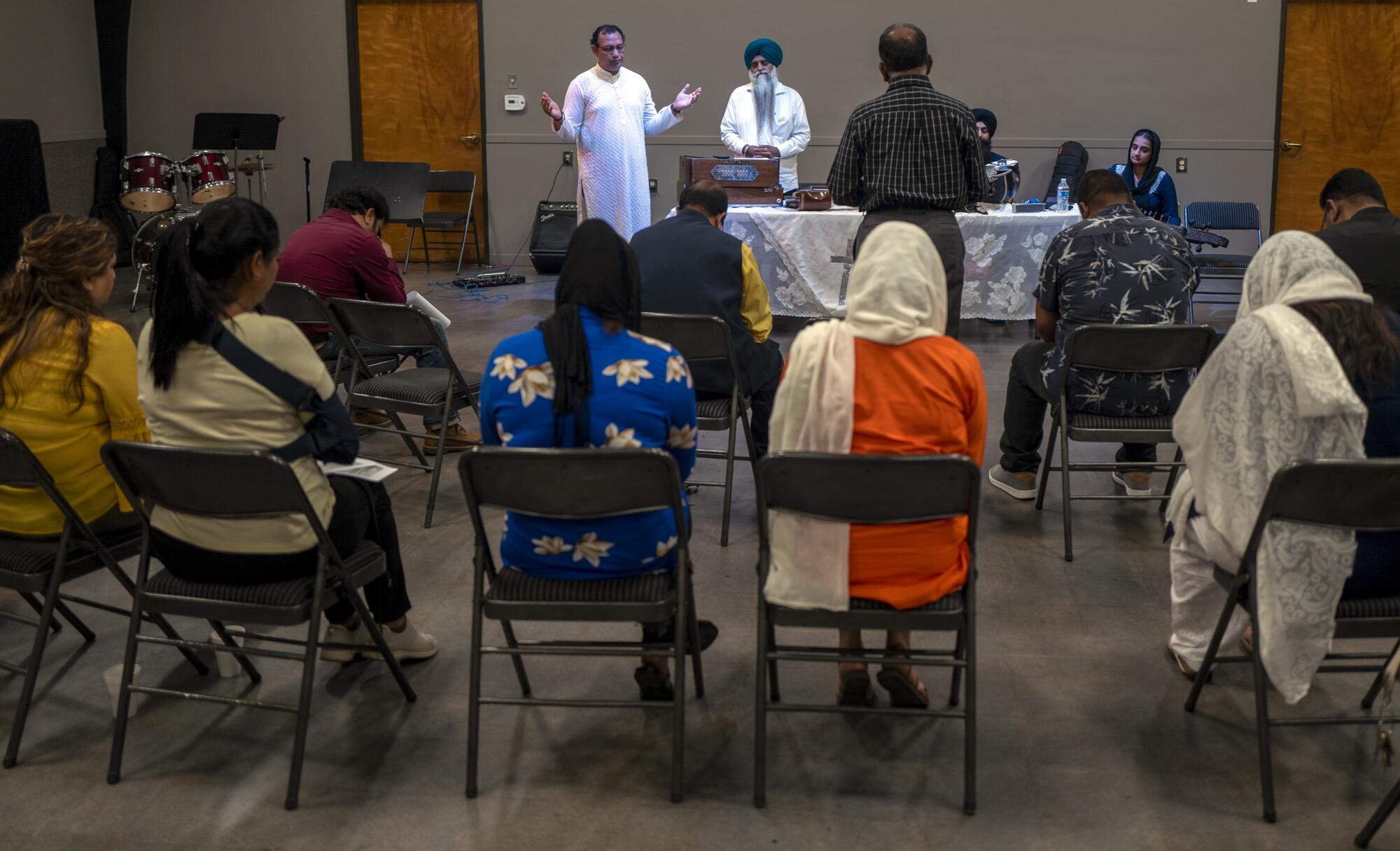

About two dozen members of Artesia City Church — a Christian Reformed congregation in Artesia whose members are mostly of Indian and Pakistani descent — gathered May 7 to do something that was banned in California during the pandemic: sing inside their house of worship.

They sang Psalm 91 in Punjabi: Surely He shall deliver you from the snare of the fowler and from the perilous pestilence.

It has been a celebratory spring at the church, which, after months of Zoom, resumed full indoor services shortly before Easter. About 90% of the congregation’s 70 or so members have been vaccinated, and they consider it a blessing that none died of COVID-19, said Pastor Eric Sarwar.

“It’s kind of like coming back to life, you know? You are out of the prison from the pandemic, the lockdown, the uncertainty, meeting and singing together as a church,” Sarwar said. “I think these are aspects for which we are glorifying God.”

But it is a tempered joy.

Member Joshua Masih calls loved ones in India in the mornings and evenings. He just wants to talk to them, he said. To insist they stay inside.

Church elder Matthew Khokhar, whose large family is mostly in Jammu and Kashmir, said he knows of at least seven relatives who have COVID-19. A 45-year-old cousin died a few days ago.

Sarbjit Singh, a Sikh man from Burbank, joined the worship service, where he played a saranda, a stringed folk instrument.

Singh, 58, rejoiced when he got his Pfizer vaccine earlier this year. Now, he spends his days coordinating — through the Khalsa Care Foundation Sikh gurdwara in Pacoima and other organizations — how to send money and supplies overseas.

Two of his uncles and a cousin in New Delhi have died. So have several friends in the Punjab region. A cousin is now in intensive care in the city of Amritsar.

One friend lost his mother to COVID and told Singh that when he went to the crematory in New Delhi, they gave him a token and asked for his information. The token had No. 201 — the number of bodies that had to be burned first. The friend waited over three days to cremate his mother.

“Basically, it has reached every family, everywhere,” Singh said. “People are dying in hospitals. People are dying outside hospitals. People are dying inside their homes. People are dying outside their homes. People are dying on roads. People are dying on streets. People are dying on curbs. People are dying everywhere.”

The next morning, Parth Parikh, a 32-year-old pharmacist, pressed his palms together as a Hindu priest led morning prayers at Sanatan Dharma Temple in Norwalk before giving shots at a vaccination clinic there.

Every Saturday, Parikh, who runs Pico Care Pharmacy in Pico Rivera, works at the clinic, which had given 6,046 shots as of last week, including to the temple’s priest.

Parikh speaks Hindi and Gujarati, and the clinics have attracted South Asians who feel most comfortable speaking in their native languages, he said.

Parikh’s parents, who are in their mid-60s, live in Ahmedabad, in western India. They got COVID-19 in November and were sick for more than two weeks.

Back then, the care was better, he said. A hospital provided outpatient services, sending doctors and nurses and IVs to their home. The local government, he said, put a quarantine notice on their door. Police officers checked on them twice a day.

“I just had to stay patient,” Parikh said. “You can’t go visit them. You can’t help.”

After they recovered, he said, they were relieved to have gained some natural immunity. But now, some of their friends have reported getting infected twice. They have now gotten both doses of the Covishield vaccine but don’t leave home.

His mother’s two sisters tested positive about a month ago. They recovered.

But his grandmother’s sister died from the virus a few days ago. Family spent days trying to find a hospital bed, but when they finally found one, it was too late. Now, her husband is hospitalized.

“It almost feels like the whole air is full of virus,” he said. “The expectation is everyone is going to be COVID positive at the end of this whole thing.”

In the temple courtyard, Sawhney — president of Saahas for Cause, a nonprofit that supports South Asian immigrants — watched people during their 15-minute waiting period after receiving their shots.

“It’s so beautiful,” she said of the clinics, which her organization coordinates.

There are some Saturdays the clinics are so busy that she goes home with an aching back, but a smile on her face. Other days, she walks through the Little India neighborhood in Artesia, trying to persuade people to get their shots, like she did in January.

Sawhney’s mother, a 65-year-old widow, was living with her in Cerritos when the pandemic began in March.

“We kept her in the house,” Sawhney said. “That really got to her. Her emotional health. Her mental health.”

By the fall, case numbers were starting to spike in L.A. County, and the situation seemed fine in India, where Sawhney’s brother’s wife had just had a baby. In November, her mother boarded a flight.

“It’s kind of like coming back to life, you know? You are out of the prison from the pandemic, the lockdown, the uncertainty, meeting and singing together as a church. I think these are aspects for which we are glorifying God.”

— Pastor Eric Sarwar, Artesia City Church

“We were nervous here,” Sawhney said. “We were telling her, ‘Don’t invite people! Wear a mask!’”

But people there felt the threat had largely passed, her mother told her.

Her mother, who got her first Covishield shot about a month ago, was between doses when she tested positive. She is staying with Sawhney’s brother, a Hyderabad hotel manager, who was also between shots when he got COVID-19, Sawhney said. His wife and 7-month-old son have not gotten sick, but they are isolated in the house.

Sawhney’s mother-in-law, also a widow, was in India most of last year. In November, she had a stroke, and Sawhney and her husband brought her to California to take care of her.

“The same saga happened,” Sawhney said. “She was homebound, lonely. That claustrophobia, the loneliness, the depression, the anxiety, all of that kicks in.”

She got her Moderna vaccine around January. But in March, she went back to India, just as its health minister declared the country had reached the pandemic’s “endgame.”

In early April, she had another severe stroke. Her left side was paralyzed, and she started using a wheelchair. Her sister, who lived nearby, had been helping her, until she and everyone in her household tested positive for COVID-19.

Earlier this month, Sawhney’s mother-in-law flew back to California. She had to test negative for the virus before boarding the plane.

Sawhney, a mental health clinician, and her husband, a physician, get calls at all hours of the day and night, from the U.S. and India.

Sawhney is on a WhatsApp group chat with classmates from her high school in the city of Pune.

“We were all sharing our school-time stories,” she said. “Happy, funny, silly, naughty story. Very soon, our group’s atmosphere changed to one of grief and sorrow. The naughtiness and laughter is gone. We are all just praying for each other.”

Times photographer Irfan Khan and researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.