‘We need to fix this city’: Post-Garcetti Los Angeles at a crossroads

- Share via

On the 26th floor of City Hall, one lesson in the history of Los Angeles is abundantly clear. Accomplishments of the past are never greater than the problems of the present.

Hidden in the corridors of this granite aerie are portraits of nearly 50 former mayors. Most are strangers, whose legacies have been overshadowed by the never-ending demands of an ever-evolving city.

Eric Garcetti is about to join this gallery, and his premature departure — ambassadorship, India — means Angelenos must again look to the future and consider a new mayor whose agenda will be more urgent and complicated than ever before.

As Los Angeles emerges from the shadows of a global pandemic, its economy is a patchwork of inequity and privilege. Homeless camps have spilled from streets and underpasses onto beaches and city parks.

Families face the prospect of eviction against a backdrop of rising housing costs. Violent crime is on the rise, and racial bias and abuse have undermined confidence in the Police Department.

Garcetti leaves a city that is, by many accounts, still broken, and imagining his successor — whether interim or elected — may require looking beyond the past: beyond the coalition-building skills of Tom Bradley, the entrepreneurial savvy of Richard Riordan, the institutional memory of James Hahn, the zeal of Antonio Villaraigosa and Garcetti’s own steady hand.

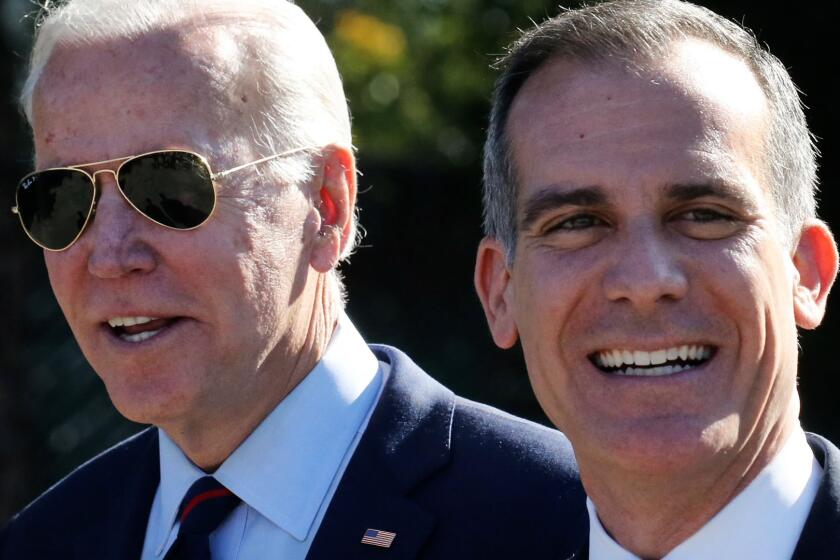

President Biden selected Eric Garcetti to become U.S. ambassador to India. Garcetti would step down as L.A. mayor after Senate confirmation.

The future holds unseen possibilities. A woman has yet to hold the office, and except for Bradley and Villaraigosa, former mayors have not reflected the city’s increasing diversity.

If the stakes are high, so are the expectations for a job that was constrained by the 1925 City Charter (slightly revised 70 years later) and is seen by many as largely symbolic.

“The mayor is a figure whose task it is to be a mirror of the city’s best aspirations,” said cultural historian D.J. Waldie, “and be honest about the city’s limitations, to point out where the aspirations have failed without being a scold.”

Though the mayor’s authority is limited — the 15 council members arguably have more influence — the office does manage the city’s financial decisions, which may be the first place to set priorities.

“We need to fix this city,” said former Councilwoman and county Supervisor Gloria Molina, whose remedy begins with a practicality: “Making sure that there is a budget for the needs of everyone.”

But the job needs more than a seasoned bureaucrat. For Molina, the ideal candidate will be bold, strong and capable of taking in the breadth of Los Angeles and not be beholden to neighborhoods, lobbyists or developers, constituencies that determine success at the polls.

The White House has yet to say whether Mayor Eric Garcetti will become an ambassador. But the jockeying to fill his seat is underway.

The best mayor, she said, would be “unelectable,” a fitting description if the City Council names an interim mayor who assumes office without having to campaign and would be free to make decisions without political consequence.

“Being elected,” Molina said, “requires you to acquiesce to major influencers, and that compromises your ability to address the very issues that need to be addressed. That is why we are in the situation we are in.”

Community activist Najee Ali has a simple prescription for when the next mayor is sworn in: Pick up where Garcetti left off.

“If I were to give Garcetti a grade, it would be for me a B-plus,” he said, “and the only reason he doesn’t get an A is he didn’t have enough time to complete everything that needs to be done for our city.”

Housing, law enforcement, public safety and social programs are the city’s immediate priorities, said Ali, who praised Garcetti’s commitment to bringing in state and federal funds for housing and for reallocating the LAPD budget for gang intervention and mental health services.

“Those are not sexy issues, but they are important quality-of-life issues,” he said.

Luis Rodriguez, the city’s poet laureate from 2014 to 2016, believes the job requires a vision for the future that will address the city’s economic disparity and its need for social healing. The answers are in the problems, he said.

Los Angeles is in crisis because we are holding on to “dead ideas, dead organizational principles, dead ways of doing things,” and only by letting go will new ideas and innovation come forward, Rodriguez said.

“People are asking for radical change,” he said, “but radical is not overturning things or burning things down. It is looking instead at the economic, cultural and social roots for all of this.”

Rodriguez added that gentrification is among the city’s most critical issues because of its effect upon mostly Black and Latino communities. Failure to address this problem or apply meaningful remedies has only made homelessness — along with drug and alcohol abuse and mental illness — worse, he said.

Los Angeles has to come to terms with the interconnectedness of these problems, said Bill Deverell, director of the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West, otherwise the efforts will be piecemeal and temporary.

“We need a mayor who recognizes that these challenges are not discrete,” he said. “Housing equity, public health, law enforcement, jurisprudence, racial and ethnic parity — they are all one gigantic tapestry. Recognizing that interconnectedness is crucial and fundamental to making productive change that lasts.”

Architect Wendy Gilmartin, who is on the advisory board of the Los Angeles Forum for Architecture and Urban Design, agrees.

The new mayor, she said, has to see the city’s problems in the aggregate and understand how intertwined they are. Los Angeles’ history of land speculation and its continual obsession with real estate, for example, have played a role in fostering racial inequity in the city, she said.

“We need a mayor who recognizes these connections,” she said.

While Gilmartin praises some of Garcetti’s initiatives, she would like to see them taken further. Garcetti’s “granny flat” — or accessory dwelling unit — program is an important step in bringing density into the city, but its implementation has not been as progressive as the concept. For that, she recommends an overhaul, as Riordan did, of the city’s Department of Public Works, where permitting and planning take place.

Gilmartin similarly questions the value of a guaranteed basic income plan that would provide $1,000 a month to 2,000 low-income families when an average one-bedroom unit rents for $2,400.

“If you are struggling to pay a mortgage, you won’t build an accessory dwelling unit in your yard,” she said.

Coming out of the pandemic, Gilmartin would like to see leadership that can advance novel approaches to the housing crisis, such as converting vacant office space into subsidized apartments.

The housing crisis — and its corollary, homelessness — is also on the mind of Lew Horne, a Los Angeles-based division president for the real estate brokerage firm CBRE. Anything else, he said, is “a distant second.”

Horne would like to see a new mayor with both political and business experience and a willingness to make decisions that “are not going to be popular with everyone.”

“In business,” he said, “we look for the outcome and work backward. We work toward a ‘solve’ and not toward the management or maintenance of a problem.”

With more than 60,000 unsheltered people in the county, Horne believes that the idea of opening 50 beds at a time is inadequate.

“How do we address wholesale change?” he asked. The answer begins with a mayor who would champion reforms in zoning to allow for greater density in the city and in the California Environmental Quality Act, used to slow or stop development.

Communities also need special incentives to overcome local resistance toward housing homeless individuals.

“Everyone wants to solve homelessness,” he said, and the next mayor needs to use the “bully pulpit” to communicate not just to the City Council or the business community but to the citizens of Los Angeles what is at stake if the crisis isn’t solved.

“We have to do this, or we risk our future,” he said.

But before the future can be imagined, Eric Avila, an urban cultural historian at UCLA, argues for a better understanding of the habits and biases of the past. Los Angeles, he said, needs to let go of its old identity and see itself as a city, not as a disparate collection of neighborhoods, suburbs and urban centers.

“The suburban dream, predicated on the automobile and highway, is not sustainable,” he said. The automobile and highway have hurt our neighborhoods and warped our sense of public life and our sense of connectedness.

The final leg of the Metro subway that eventually will take riders from downtown L.A. into the Westside broke ground on Monday.

By investing in alternative modes of public transit, the new mayor will have an opportunity to invigorate public spaces, which in turn will bring residents together. Avila would like to see streets become more like promenades and believes the transformation would create a more healthful and dynamic urban environment. He sees police officers, for instance, walking these neighborhoods and street vendors bringing these spaces alive.

Whatever the new thinking — bold, strong, even unelectable — humility may be needed as well. Its absence on the 26th floor of City Hall is also conspicuous, where each portrait captures a steely resolve that says nothing — not war, depression (or recession), scandal or even peace — is too great to overcome.

But history paints a less certain truth. Even if the new mayor unites the city’s disparate voices, the reality is that solutions to the most stubborn problems lie beyond the reach of one person.

“Issues like homelessness aren’t just the mayor’s or the City Council’s problem,” Molina said. “They are our personal problems as well.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.