L.A. County tack stores report higher demand for ivermectin, unproven COVID treatment

- Share via

Tracey Savich, owner of Rolling Hills General Store, said she couldn’t tell if a customer was joking when he came into her store asking for over-the-counter ivermectin for animals to prevent COVID-19.

The anti-parasitic drug — commonly used to deworm horses, cows and other livestock — has been controversially touted as a preventative and treatment for COVID, particularly among those who remain skeptical about the vaccines. Although its efficacy against COVID has been debunked, some Californians have managed to acquire prescriptions from their healthcare providers.

But others who were turned away are flocking to tack and feed stores in search of the over-the-counter version of the drug intended for farm animals.

“They’re seeking us out, and they know that we have it for horses,” Savich said. “It’s just sad that it’s gotten to this now.”

Sammy Weiss, assistant store manager, said that although she doesn’t explicitly ask customers if they’re purchasing ivermectin solely for their animals, it’s been easy to identify those who may be intending to use it for personal consumption.

“Everybody that comes in here, we’re very familiar” with, Weiss said. “We know who’s a horse person and who’s not.”

In Agoura Hills, David Manhan, owner of West Valley Horse Center, said small surges in ivermectin sales are common during the horse and cattle deworming season, which runs from June to July and December to January. But in recent weeks, his store is averaging two or three phone calls a day from people claiming to have horses and asking if he has ivermectin products in stock.

On Aug. 31, the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Veterinary Medicine said in a statement to retailers and veterinarians that there were “continued concerns that there are people using animal formulations of ivermectin to treat or prevent COVID-19 in humans.”

“Even if animal drugs have the same active ingredient as an approved human drug, animal drugs have not been evaluated for safety or effectiveness in humans. Treating human medical conditions with veterinary drugs can be very dangerous,” the statement read.

Although ivermectin is prescribed to humans in much smaller doses for the treatment of scabies, lice, river blindness and other parasitic infections, the FDA has warned against consuming ivermectin products found in tack and feed stores, which contain a much higher dosage of the drug and can lead to poisoning.

Steve Lyle, director of public affairs for the California Department of Food and Agriculture, said certain retailers, including feed stores, that sell restricted livestock drugs such as ivermectin must be licensed by the department and keep a detailed log of sales, including the customer’s name, address and what species the product will be used on.

But that requirement applies only to ivermectin products labeled by the manufacturer for use in cows and sheep, not horses, Lyle said. This can serve as a loophole for those who might want to take the drug as a medical treatment for themselves without needing to disclose their purchase.

Weiss said she and Savich have attempted to discourage customers from buying the horse dewormer for themselves, putting up signs in their store reminding customers that taking veterinary ivermectin can be harmful and potentially lethal. But some customers are insistent, she said, even bringing along printouts of reports of its supposed effectiveness.

“The bottom line is, if they really want it, they’re going to get it,” Weiss said. “You can ask all these questions and you can tell them everything about why they shouldn’t do this, but at the end of the day, they’re going to do what they’re going to do.”

Savich said suppliers have already begun to sell out of ivermectin, which she says is a sign that, as products fly off of the shelves elsewhere, a surge in sales could soon hit her store. After trying to place an order last week with seven distributors, she was able to find only five tubes of topical ivermectin paste for horses.

“I looked at the supply list and everything was zero,” she said. “It’s going to be bad, and there’s nothing we’re going to be able to do.”

Savich said she worries about customers potentially hurting themselves if they attempt to self-medicate with a product intended for a 2,500-pound animal. A normal dose of ivermectin prescribed for a human with lice or scabies, for example, is approximately 68 micrograms per pound of body weight, according to the Mayo Clinic. The average dosage of ivermectin in a tube of over-the-counter horse dewormer is 91 micrograms per pound.

Stuart Heard, executive director of the California Poison Control System, said the center has received about 30 calls from people who have ingested some form of ivermectin and experienced nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, dizziness and confusion. But in high enough doses, such as in horse and cattle dewormers, Heard said the drug can cause serious side effects, including hallucinations and seizures.

“We certainly advise people every time: Do not use this for COVID,” Heard said. “It is ineffective and it’ll just make you feel ill. It does not help COVID.”

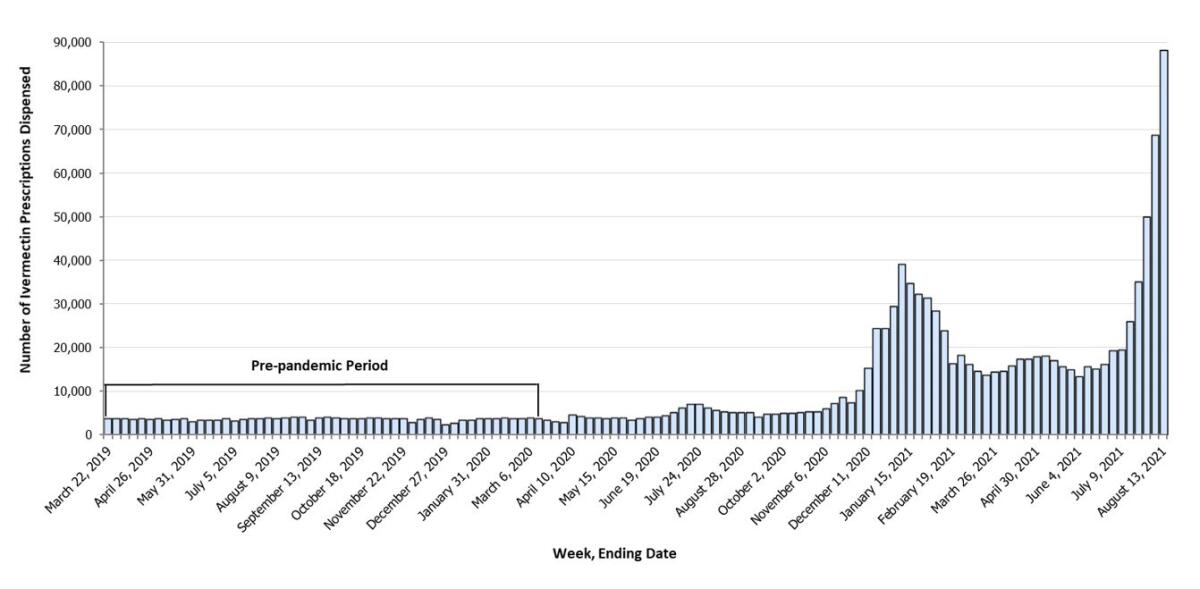

Heard said using an anti-parasitic drug such as ivermectin to treat a viral infection like COVID-19 is worthless, regardless of the dosage. Yet some physicians across California and the nation continue to write prescriptions for patients upon request. According to the CDC, more than 88,000 ivermectin prescriptions were written in the U.S. in the week that ended Aug. 13, compared with an average of about 3,600 a week before the pandemic.

Weiss and Savich, who have horses of their own, said the sudden shortage in ivermectin in other states has them and other horse owners in the community worried about how they’ll be able to treat their animals, if needed, especially in the winter deworming season.

“It’s stressful to think about. What if I can’t deworm my horses?” Weiss said. “If I can’t deworm my two horses — and there’s a shortage — what am I going to do?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.