Sirhan Sirhan’s possible parole creates divide in Kennedy family and beyond

- Share via

Carol Germain lives on a quiet, tree-lined street in Pasadena a few houses down from the brother of Robert F. Kennedy’s murderer.

For 30 years, she has watched TV crews pop by the middle-class neighborhood, where Munir Sirhan’s fenced-off home was featured on a Pasadena true-crime bus tour. At the brother’s request, she recently signed a letter supporting Sirhan Sirhan’s release.

“He’s 77,” she said. “He probably just wants to come and sit in the backyard.”

But Germain understands the whirlpool of emotions surrounding the decision last month by California parole commissioners to recommend the release of the man convicted in one of the most infamous political assassinations in American history.

The recommendation has stirred intense debate in many corners — among the Kennedys, others who remember the killing, and even in the Pasadena neighborhood where the convicted killer hopes to settle with his brother if he is freed.

At its core is the question of how much mercy should be shown to people who commit horrific crimes, including those that may have changed history. Kennedy was a leading candidate for president when he was fatally shot on June 5, 1968, at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles at age 42.

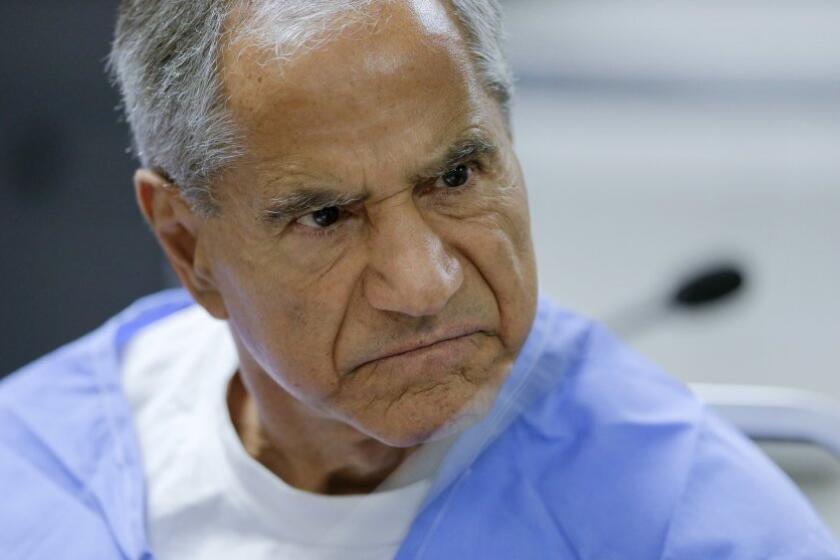

Sirhan, the man convicted of assassinating Robert F. Kennedy more than 50 years ago, has been recommended for release by a California parole board.

Sirhan’s testimony during a virtual hearing — in which he said he didn’t remember shooting the senator but expressed remorse “if I did in fact do that” — has been insufficient for many members of the Kennedy family.

“Our family and our country suffered an unspeakable loss due to the inhumanity of one man... he should not have the opportunity to terrorize again,” Ethel Kennedy, the late senator’s widow, who was pregnant with their daughter when he was assassinated, said in a statement.

Although six of his children said they were devastated by the commissioners’ decision, two have voiced support for Sirhan.

Douglas Kennedy told the panel that he’d lived in fear of Sirhan but now saw him “as a human being worthy of compassion and love.” Robert Kennedy Jr., who has echoed claims that a second gunman killed the senator, told the Los Angeles Times he was “happy that the justice system showed some humanity.”

Advocates of rehabilitation point to the small fraction of people who have committed crimes after being released from life sentences. A 2020 report by California’s prison system states that only 2.3% of the 688 such inmates freed in fiscal year 2014-15 were convicted of a new crime — the majority of them misdemeanors.

“I don’t think a single or even a series of behaviors defines the worth of a human being,” said Suzanne Neuhaus, who worked for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation from 1988 to 2015 as a parole agent and victims’ services specialist. “Are people worthy of an opportunity for change? Does a just system require mercy?”

Sirhan, a Palestinian immigrant, was 24 when he fatally shot the senator minutes after Kennedy’s speech on the night he won the California Democratic presidential primary. He later said he had felt angered by Kennedy’s support for Israel.

He initially faced the death penalty, but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment after California briefly outlawed capital punishment in 1972.

Sirhan has been consistently denied parole. At a 2016 hearing, commissioners decided he hadn’t shown enough remorse or insight into why he had committed a crime that “clearly affected the potential of this nation.”

Sirhan’s supporters say he’s recently doubled down on efforts to change that.

Over the last year, they note, Sirhan began working with several prisoners at the Richard J. Donovan Correctional Facility in San Diego who are trained to help other inmates with conflict resolution.

The group worked with Jen Abreu, a facilitator for the Alternatives to Violence Project, who said Sirhan spent hours every day working with members of the group on concepts such as empathy and remorse.

“They would talk about the material and how these giant abstract concepts applied to his life,” Abreu said, “really trying to get him to understand the nuances of this life crime.”

At the hearing, Sirhan told commissioners that he had attended self-help programs and meditates regularly. While he began crying when asked how he felt about the Middle East, he said he would try to detach himself by “dropping it from my conscience.” At 24, he said, he had wanted to be a “solid member of the community” and that’s what he hoped to do with the rest of his life.

Commissioner Robert Barton said Sirhan had no criminal history before the killing and had not committed any serious violations for several decades. The board was required to give “great weight” to the fact that Sirhan qualified for youth parole, which operates under the rationale that the parts of the human brain responsible for understanding consequences hadn’t fully developed yet, he said.

Although the board considered the political nature of the killing, Barton said, denying parole requires evidence of dangerousness and an unreasonable risk to public safety.

But much of the opposition to Sirhan receiving parole has focused on his crime.

Heidi Rummel, co-director of USC’s Post-Conviction Justice Project, said that the case is complicated by the fact that Sirhan’s sentence was commuted from death to life imprisonment.

“The faction that’s saying it’s unfair to release him should be arguing with California sentencing laws,” she said. “It’s not an argument with the parole board.”

Christopher Hawthorne, the director of Loyola Marymount University’s Juvenile Innocence and Fair Sentencing Clinic, said that the board cares about Sirhan’s remorse and that “the current thinking is that if he understands what led him to that [the crime], he also understands how to live a lawful life going forward.”

But Robert Weisberg, the co-director of Stanford University’s Criminal Justice Center, said that the parole board has discretion to determine whether Sirhan’s release would inflict emotional harm and social distress even if he would never commit another crime.

The decision must still be reviewed by parole legal staff and can be blocked by Gov. Gavin Newsom, or whoever might replace him following the recall election.

Newsom has rejected the board’s decisions in the past. In November, he reversed parole for Charles Manson follower Leslie Van Houten, 72, who had spent about five decades in prison for the killings of Leno and Rosemary LaBianca — the fourth time a governor had blocked her release.

In a letter submitted to the parole board, a Cleveland resident described how in his youth he had knocked on doors to get people to vote for Kennedy. The senator, he said, “was a person who I loved and respected and in whom I had deep confidence that he would put a quick end to that unjust and immoral war in Vietnam.”

But Sirhan, he said, “has been punished beyond any reasonable humane realization.” He urged commissioners to let Sirhan’s remaining time alive “be peaceful.”

Most of Kennedy’s children disagree.

Maxwell Kennedy, who served as a prosecutor for several years and was a toddler when his father was assassinated, told The Times that “retributive justice is vital to my sense of what the justice system is,” holding that people who commit capital murder should not be eligible for parole.

“If you say you can kill a politician if you’re willing to give 50 years of your life, we are setting a dangerous precedent for Americans, and we are encouraging the dissolution of the rule of law,” he said.

In an op-ed for the New York Times, Rory Kennedy wrote that she had never met her father — having been born six months after his death — and that the loss “has had impact beyond measure.” She wondered whether Sirhan had not already been shown compassion when his death sentence was changed to life in prison.

“It is a high-minded notion, after all, the belief that everyone — everyone — deserves a chance for rehabilitation and, after having served enough time in prison, even parole,” she said.

Sirhan’s parents and four of his five siblings are dead. Angela Berry, Sirhan’s attorney, has said there’s a chance that Sirhan could be deported if he is released — saying he holds a Jordanian passport. But if not, he would like to return to his family home in Pasadena.

For more than a decade, the Sirhan family home was a stop on Pasadena Confidential, a bus tour to places associated with historic and obscure crimes. Richard Schave, who ran the tours with his wife, said they were never comfortable with the police investigation into Kennedy’s death and chose to add the Sirhan home as a stop in order to ask questions about L.A. history that “we don’t think are looked at closely enough.”

Reaction to his possible release has played out in Pasadena through the Nextdoor app, with some residents saying they would be opposed to living close to a murderer.

But several who live on Munir Sirhan’s street have said they wouldn’t be bothered by Sirhan’s return, pointing to their respect for his brother. One man, who declined to provide his full name, said that Munir had been “such a good neighbor.” He recalled how his own prom had been held at the Ambassador Hotel where Kennedy was shot.

“I wouldn’t have a problem with it, to tell you the truth,” he said, standing on his front porch holding a hummingbird feeder. “I understand it’s polarizing. It’s one of the things you fight about, like the Manson family.”

Germain, Munir Sirhan’s neighbor, said that while she supports his release, she understands those who say his crime had too great of an impact — on the Kennedys and on history — to merit him walking out of prison.

“I would feel that 100% if it was my family,” she said. “I don’t think I could forgive anyone who assassinated my father.”

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.