Inland Empire COVID-19 hospitalizations far worse than L.A. Here’s why

- Share via

For Monica Escamilla, the text messages came in like clockwork.

The registered nurse was supposed to have the rest of the day and evening off from her job at Hemet Global Medical Center. But the texts from her supervisors came in anyway, asking for people to take on another shift — day or night. The hospital, located more than 75 miles southeast of Los Angeles, was going to be short on nursing staff. Again.

It’s been the norm since the COVID-19 pandemic began last year.

“I feel so bad. I wish I could pick up [a shift] every single day to help, but I can’t. I really can’t,” Escamilla said. “And not just because I physically can’t, but you need a day or two to take care of your own things at home. ... It hurts me because it’s like, ah, they’re short again and they’re short again. ... I wish I knew how to get help for them.”

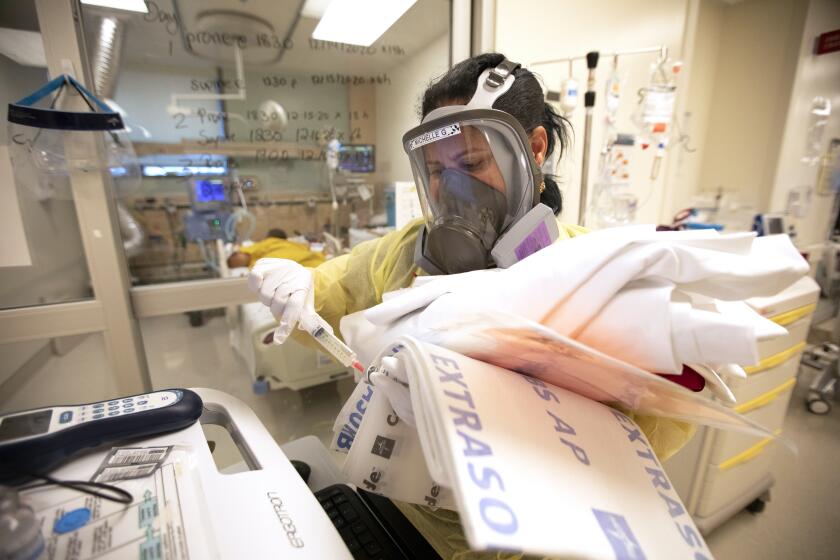

Escamilla works in the Inland Empire, where the Delta variant’s summer surge pummeled hospitals more than anywhere else in Southern California, according to a Los Angeles Times analysis.

Doctors, nurses, technicians and other hospital support staff have endured daily pressure to take on more shifts amid burnout and understaffing. Although the number of COVID-19 hospitalizations is gradually dropping, medical staff fear another surge if more people don’t get vaccinated before the autumn and winter cold and flu season.

The Inland Empire hit its peak of hospitalizations on Sept. 1, when 1,246 coronavirus-infected people were hospitalized, the equivalent of 28 hospitalizations for every 100,000 residents.

That’s 56% worse than the peak for the three-county coastal region of Los Angeles, Orange and Ventura counties, which recorded 18 hospitalizations for every 100,000 residents at its peak on Aug. 17; and also worse than San Diego County, which peaked on Aug. 27 with 20 hospitalizations for every 100,000 residents.

The Times analysis found that no other counties in Southern California have had a higher hospitalization rate this summer — including impoverished and largely agricultural Imperial County on the Mexican border, which had Southern California’s worst hospitalization rate during each of the pandemic’s first three surges last year, but not during the fourth wave this summer.

Despite previous coronavirus vulnerabilities — the result of overcrowded homes, high rates of poverty and huge numbers of essential workers — Los Angeles County, too, observed significantly lower hospitalization rates than the Inland Empire.

Vaccination rates are likely influencing the varied hospitalization numbers. The Inland Empire has the lowest vaccination rate in all of Southern California.

Just 47.2% of residents of all ages in San Bernardino County are fully vaccinated, and only 50.4% of residents in Riverside County are. By contrast, 60% of L.A. County residents are fully vaccinated, as are 61.3% of Ventura County residents, 62.1% of Orange County residents, 64.5% of San Diego County residents and 66.2% of Imperial County residents.

The pace of COVID-19 vaccinations in Los Angeles County is so slow that there’s a risk of a “cycle of repeated surges every few months,” Los Angeles County’s public health director warns.

At Arrowhead Regional Medical Center in Colton, the severely ill patients in the intensive care unit are unvaccinated, and an “overwhelming majority of them regret not getting the vaccine,” said Dr. Sam Hessami, the hospital’s chief medical officer.

The hospital has pushed to give at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine to as many patients as possible regardless of their reason for coming in. Hessami said the staff has aimed to answer any concerns patients have about the efficacy and safety of the vaccines rather than simply telling them to get vaccinated.

But, Hessami says, he is most worried about potential understaffing if not enough doctors, nurses or housekeeping workers get vaccinated. Once the California Department of Public Health’s policy on mandated vaccinations for health workers goes into effect at the end of the month, some will have to be let go if they refuse. The hospital has been holding town halls to provide as much information as possible to staff members about vaccination efforts.

“You’re looking for the swing voters, those people who are willing to accept facts and change their minds,” Hessami said. “Those who are already entrenched in their ideological beliefs, you can’t change their minds, unfortunately.”

Riverside County has also been faced with abnormally high non-COVID-19 hospitalizations, with those patient volumes as much as 25% higher than normal for this time of year, said Bruce Barton, director of emergency management for Riverside County.

So even though the number of hospitalized COVID-19 patients has remained lower in Riverside County than during the winter surge, overall, the county has been just as busy this summer as it was last winter.

Ninety percent of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Riverside County are unvaccinated, Barton said, a percentage that has remained consistent throughout Southern California.

Witnessing so much pain over the last year from the COVID-19 pandemic will likely take a major toll on healthcare workers’ mental health, experts say.

For Escamilla, she went back to work from maternity leave right before the summer Delta surge began. Since returning, she’s often donned an N95 mask her entire shift and added even more hand-washing to her routines. When she comes home, she changes in her garage and leaves her shoes there out of fear of passing anything on to her 8-month-old baby and 3-year-old toddler.

The surge has kept Escamilla and her co-workers busy during all hours of their shifts. Ideally, she and other nurses would have no more than four patients to care for, but the increased need and understaffing have meant sometimes taking on five or six patients instead.

They often are filing special “assigned over objection” forms, noting the intensified patient loads and work conditions. If there’s not enough staff on a shift, it increases the load for everyone and means patients are waiting longer for hospital beds.

“[People] don’t see all of the moving parts that go on behind the care,” Escamilla said. “I think it’s getting a little better now that nurses have been kind of put in the spotlight with all of this during COVID, but I do feel that their misconception is they don’t think we’re doing enough.”

Understaffing across departments has meant working double time, not just providing care for patients but also doing the tasks of support staff. That includes fetching blankets or juice, drawing blood, retrieving medication from the pharmacy or blood from the blood bank and going to the laboratory for patient tests and results. Escamilla said it’s not uncommon for staff to realize during their shifts they have not used the restroom or drunk water for two or three hours.

Amid all this, Escamilla is pumping breast milk for her baby. However, she does not always have time to walk to the hospital’s lactation room and instead goes to a storage area in the break room. It’s private enough but still close to her patients.

“I just try to find that right time where all of my patients are OK for a couple of minutes and I can have someone help me watch my patients,” she said. “It’s definitely been a task.”

California is searching for nurses, doctors and other medical staff, perhaps from as far away as Australia amid the coronavirus surge.

Many California hospitals, including those in Los Angeles and Fresno counties, also are struggling to get enough help amid a national shortage of nurses. It was easier to get more help during the last surge, Riverside County’s Barton said.

“All the hospitals compete for additional staffing with the same staffing agencies,” he said. “This surge is affecting many areas of the country at the same time.”

At Eisenhower Health, which operates one of the largest hospitals in the Coachella Valley, Dr. Alan Williamson, the chief medical officer, said the Delta surge has led to “young, otherwise reasonably healthy, people being struck down” by COVID-19 in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s.

The hospital often serves a highly seasonal population that nearly doubles during the winter. The summer months are often when Eisenhower Health staffers go on much-needed vacations. But amid the latest summer surge, staff members have operated at the capacities often seen during the busiest part of winter. In the last week, there were roughly 250 to 270 patients in the hospital a day compared with nonpandemic summertime numbers of 120 or 140 patients a day.

Eisenhower has been able to have traveling nurses and staff fill the gaps. The hospital is now paying traveling nurses twice as much as what they would normally be paid, Williamson said.

He likened the repeated surges to “Groundhog Day syndrome,” where over and over, the hospitals see numbers coming down only to have another wave rise up. But Williamson wonders: When can they catch a break?

“If these numbers drop back down only to see in another month or two they’re going right back up again, that is really hard to deal with,” he said. “You begin to lose hope you’re ever going to get beyond this.”

The volume of deaths and patients has taken a toll on staff, who are sometimes becoming ill from exhaustion. Williamson said the hospital is connecting employees with community resources for psychological counseling and help with burnout.

“I can’t say we’re having a huge meltdown or huge problem among the staff, but we are concerned about how long we can continue this,” Williamson said. “A year and a half and facing another six or eight months or so with no relief ... we’re very concerned about the staff and their ability to cope with those demands.”

Although chaplains are primarily tasked with supporting hospital patients and their loved ones, the pandemic has thrust them into new territory: caring for the caregivers.

Kaiser Permanente’s hospitals in Fontana and Ontario continue to have more than 80 COVID-19 patients filling their beds each day. During the severest part of the winter surge, there were over 400 patients with the coronavirus admitted in both hospitals, with over 100 in the ICU. Currently, there are 20 to 30 ICU patients with COVID-19 between the two hospitals compared with more than 100 ICU patients during the winter.

Dr. Timothy D. Jenkins, area medical director and chief of staff for Kaiser Permanente San Bernardino County, said the hospitals are “seeing significant numbers” even though they’re not as high as last winter.

“What keeps me up at night with the current surge is the fact that patients are now returning for care for all of these conditions that have been there for the last 18 months,” Jenkins said.

He said that though the Kaiser Permanente staff members have felt the summer hospitalization surge, it’s different because they’re seeing a rise in patients coming for deferred care and surgeries. The “increasing pressure on the healthcare system” to help COVID-19 patients and quickly see patients for non-COVID-19 issues such as gallstones is a challenge.

“So many patients during the winter appropriately stayed home and felt, if I’m not having an emergency, I’m going to stay home and protect myself and my family and not come in, and I’ll put up with that abdominal pain for a while longer,” Jenkins said. “Here we are 18 months in, and people are coming in now.”

For now, Escamilla is focused on being there for her two children. Between her previous maternity leave and the pandemic, they’ve been staying home and getting occasional visits from extended family. The text messages to help fill other hospital shifts will keep coming, but she knows she has to take care of herself. She said that people are afraid of increasing their exposure to COVID-19 by coming in on their days off, particularly when they’re also caring for older adults and sick family members.

“They kind of need that time to just breathe and be out of that environment like you feel you have COVID in the air,” Escamilla said. “At home, you don’t feel that.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.