Column: The first Koreatown in America, and Riverside’s role in South Korean democracy

- Share via

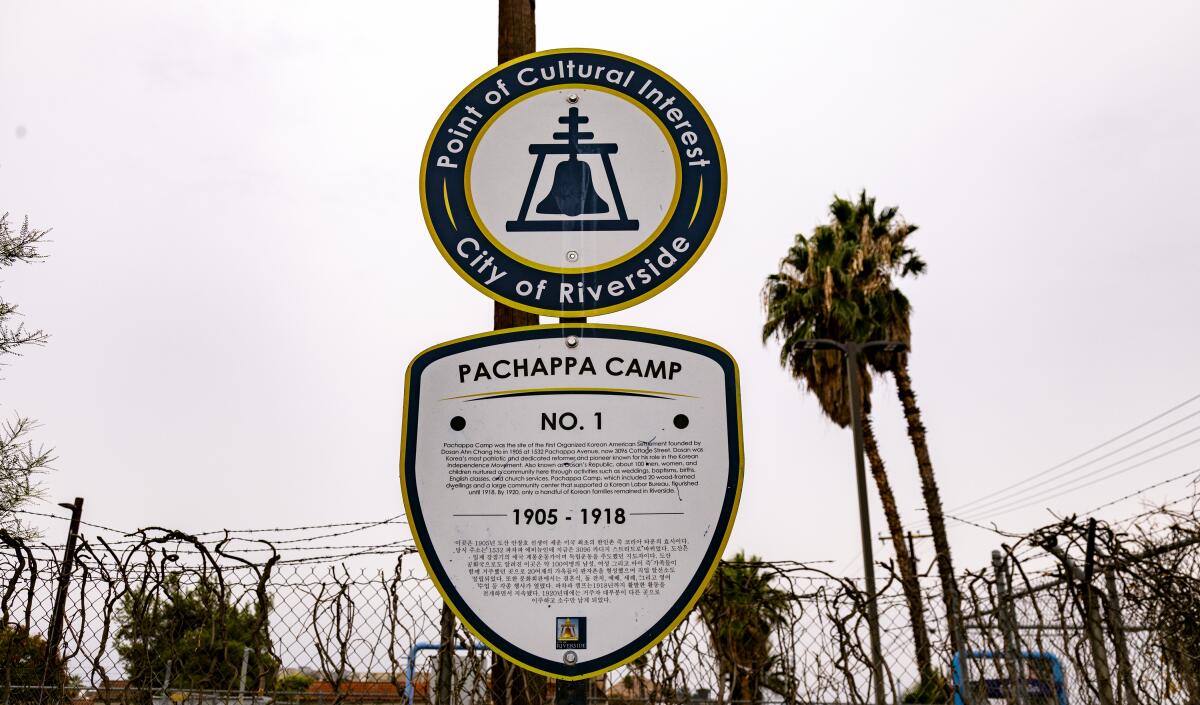

Pachappa Camp in Riverside was a far cry from the buzzy, bustling Koreatowns we know today.

Founded in 1905 as the first Korean settlement in the United States, it was a small community of about a few hundred laborers next to a heavily used set of railroad tracks, just down the street from Chinese and Japanese settlements. There was no alcohol, fighting, gambling or drugs allowed, and everyone was encouraged to wear white.

The camp was named Dosan’s Republic, after the Korean independence activist Dosan Ahn Chang Ho, who was drawn to Riverside by the highly lucrative citrus trade.

Ahn founded an employment agency for Korean laborers that eventually became a highly complex and self-governed settlement. Dosan’s Republic had no running water or electricity, but the principles of governance honed there became the building blocks for modern South Korean democracy, according to a forthcoming paper from UC Riverside professor Edward Taehan Chang.

“Dosan Ahn Chang Ho had a vision of establishing a model community. He was experimenting with it at Pachappa Camp,” Chang said.

Chang encountered the previously undiscovered settlement on a 1908 insurance company map, a tiny dot labeled “Korean Settlement.” He found an archive of a Korean newspaper, Sinhan Minbo, which revealed aspects of life and suggested that Korean Americans at Pachappa Camp and elsewhere helped found South Korean democracy. The settlement is the subject of an exhibit at UC Riverside opening Oct. 16 called “Pachappa Camp: The First Koreatown in the United States.”

Dosan’s Republic had elected officials; taxation; a separation of powers among judiciary, executive and legislative bodies; as well as two police officers with the power to search and enter private residences.

Life in the settlement was strict. Anti-Asian sentiment was a real danger, and the camp’s restrictions on alcohol, gambling and drugs were an attempt to emphasize that Korean Americans could contribute to a civilized society. Many laws focused on propriety. No Korean was allowed to leave their house unless properly dressed, and Korean women were not allowed to smoke in public. Those who partook in drugs and alcohol were subject to a series of increasing fines.

At the time, Korea was under Japanese control, and Korean independence activists around the world were raising funds, organizing and lobbying for political support. South Korea’s eventual democratic republic was organized in a series of meetings around the world. One of the most foundational meetings took place in Riverside, Chang said.

In 1911, the third national convention of the Korean National Assn. met in Pachappa Camp and passed 21 articles of governance that later appeared in documents central to South Korean democracy. The convention elected a central council that would oversee the various chapters of the KNA around the world and advocate for Korean independence.

The Korean National Assn., a political organization with chapters in major Korean settlements around the world, was functioning as a de facto government of Korea while it was under Japanese rule.

The KNA represented Korean Americans in international affairs and incidents. When an angry white mob chased Korean American workers from Hemet, U.S. officials reached out to Japanese consular officials to negotiate, prompting an outcry from Korean Americans. The KNA successfully lobbied Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan for Koreans in the United States to be recognized as Korean subjects, not Japanese.

After a cold spell decimated Riverside’s navel orange crop in 1913, the residents of Pachappa Camp left to look for work in Los Angeles and San Francisco. In 1918, the Riverside chapter of the KNA closed. In the late 1920s, Ahn was falsely accused of being a Bolshevist and deported from the United States.

Pachappa Camp was later settled by Japanese and Mexican immigrants, and in the 1950s the land was redeveloped by an oil company. Today the land is primarily occupied by a Southern California Gas Co. facility. The nearby railroad tracts have gone quiet, replaced by the muffled roar of the 91 Freeway.

Pachappa Camp existed for just over a decade. So why does it matter? Why do the histories of any immigrant enclaves matter?

To me, places like Historic Filipinotown, Pachappa Camp and Chinatown are the most powerful and tangible reminders we have of the fact that the freedoms that Asian Americans have in this country were not gifts of political benevolence. They were the hard-won spoils of a long struggle for civil rights by people of color in America. These histories of Asian American civic engagement may be buried in the archives of foreign-language newspapers, hiding in old maps or redeveloped into a gas facility, but they are there nonetheless.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.