How did California’s recent bomb cyclones compare with the ‘Big Blow’ of 1962?

- Share via

The rains triggered mudslides that buried Northern California highways, quenched reservoirs and submerged automobiles in an instant. In Sacramento, so much rain fell in a 24-hour period that it broke a record set in 1880.

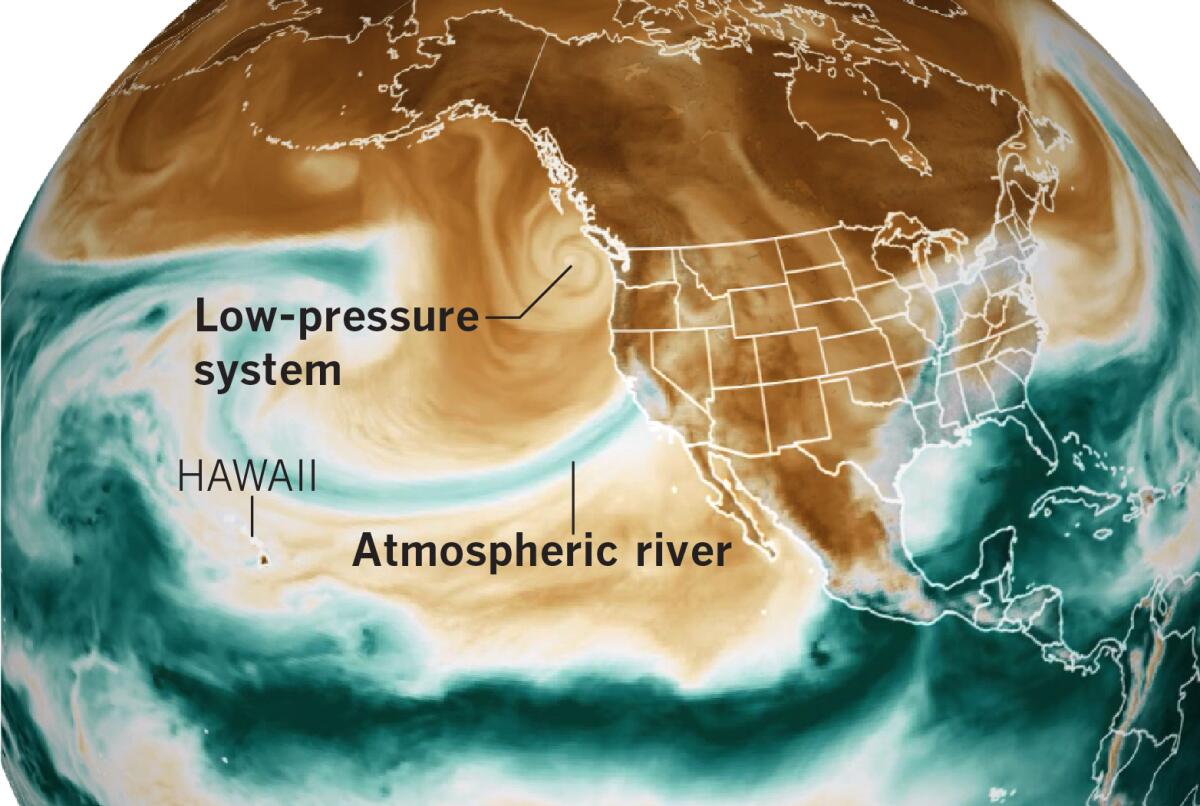

The two storms that pummeled Northern California and the Pacific Northwest with atmospheric rivers recently were extraordinary for their intensity and for the historic amount of precipitation they dropped.

They were also unusual because they occurred so early in the season. Just days earlier, California Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a statewide drought emergency.

But just how rare were these soaking storms? Unsurprisingly, in a state known for extreme weather, California has seen this sort of thing before. For example, Alex Tardy of the National Weather Service office in San Diego, cites an October storm in 1962, which is sometimes called the “Big Blow.”

That storm brought heavy rain and strong winds to Northern California. Game 6 of the 1962 World Series on Oct. 11 at Candlestick Park, between the San Francisco Giants and the New York Yankees, had to be postponed.

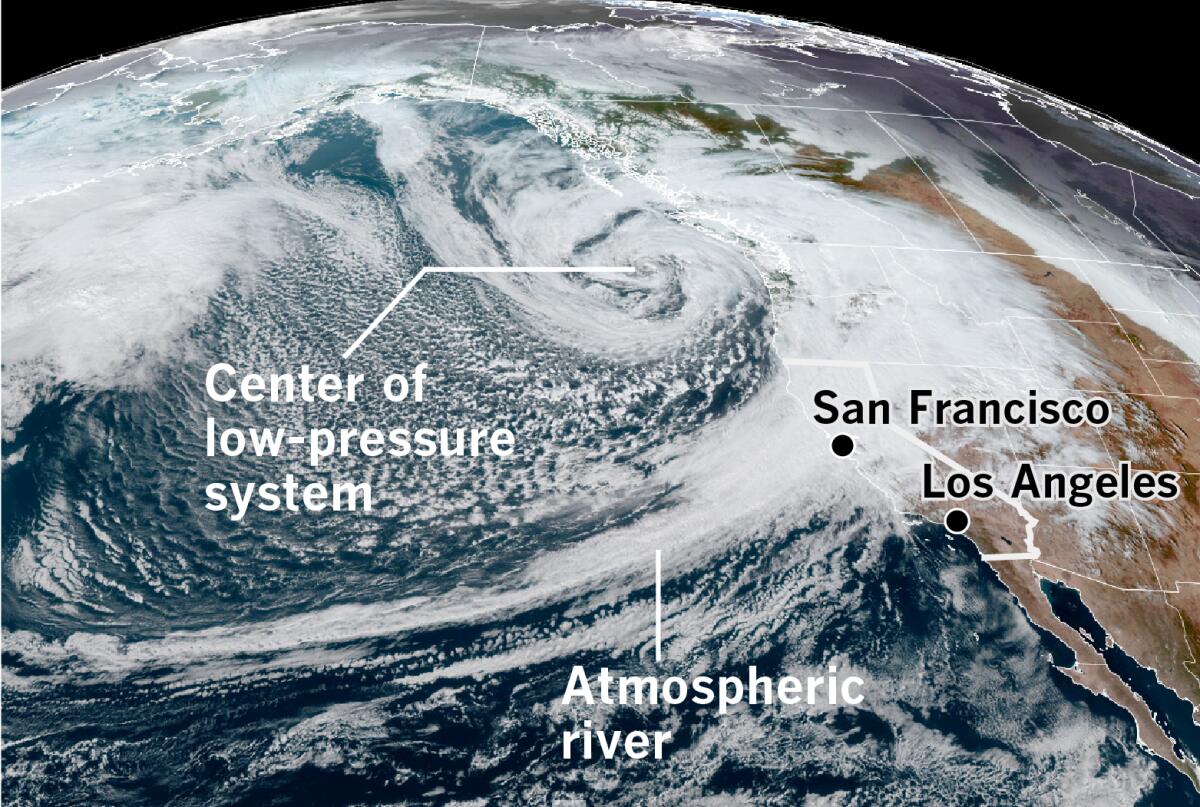

Both storms this month brought heavy rain and strong winds, and both qualified as “bomb cyclones” due to the rapid intensification of low-pressure systems, with atmospheric pressure dropping by at least 24 millibars (a measure of pressure) in 24 hours. Generally speaking, the lower the atmospheric pressure, the more intense the storm.

The first storm struck Northern California and the Pacific Northwest on Oct. 21. The second and more powerful storm hit California on Sunday and Monday and had a central pressure off the Pacific Northwest coast of 942 millibars, which is equivalent to a Category 4 hurricane. The Saffir-Simpson scale classifies hurricanes based on wind speed and central pressure. Unlike the northern part of the state, Southern California avoided much of the storm’s ferocity.

On Nov. 26, 2019, another bomb cyclone caused the lowest pressure reading recorded in California, 973.6 millibars, at Crescent City. That storm generated a 75-foot wave off Cape Mendocino.

The 1962 storm began in the Central Pacific and intensified into Typhoon Freda near Wake Island on Oct. 3. It tracked northeastward toward the Aleutians and lost its typhoon status over cooler waters on Oct. 9. The system merged with a cold front in the North Pacific and became what is called a mid-latitude cyclone, looping southeastward before rushing toward the Pacific Northwest and British Columbia.

Mid-latitude or extratropical cyclones are low-pressure systems that generally occur between 30 degrees and 60 degrees latitude in the Northern Hemisphere.

By the time the storm was off the Oregon and Washington coast, its central pressure was as low as 958 millibars. At that point, the storm was equivalent to a Category 3 hurricane.

This October’s storms also had a tropical connection, tapping into moisture from remnants of Typhoon Namtheun in the Pacific Ocean northwest of Hawaii. Namtheum dissipated west of the International Date Line on Oct. 19, and it was less of a player than Freda was, according to Jan Null, a veteran meteorologist with Golden Gate Weather Services in the Bay Area.

Although some experts believe that the former typhoon’s contribution was small, it did contribute from Oct. 16-18 by boosting the moisture that was dragged into the atmospheric river, according to Tardy. The atmospheric river reached a level 5, the strongest level.

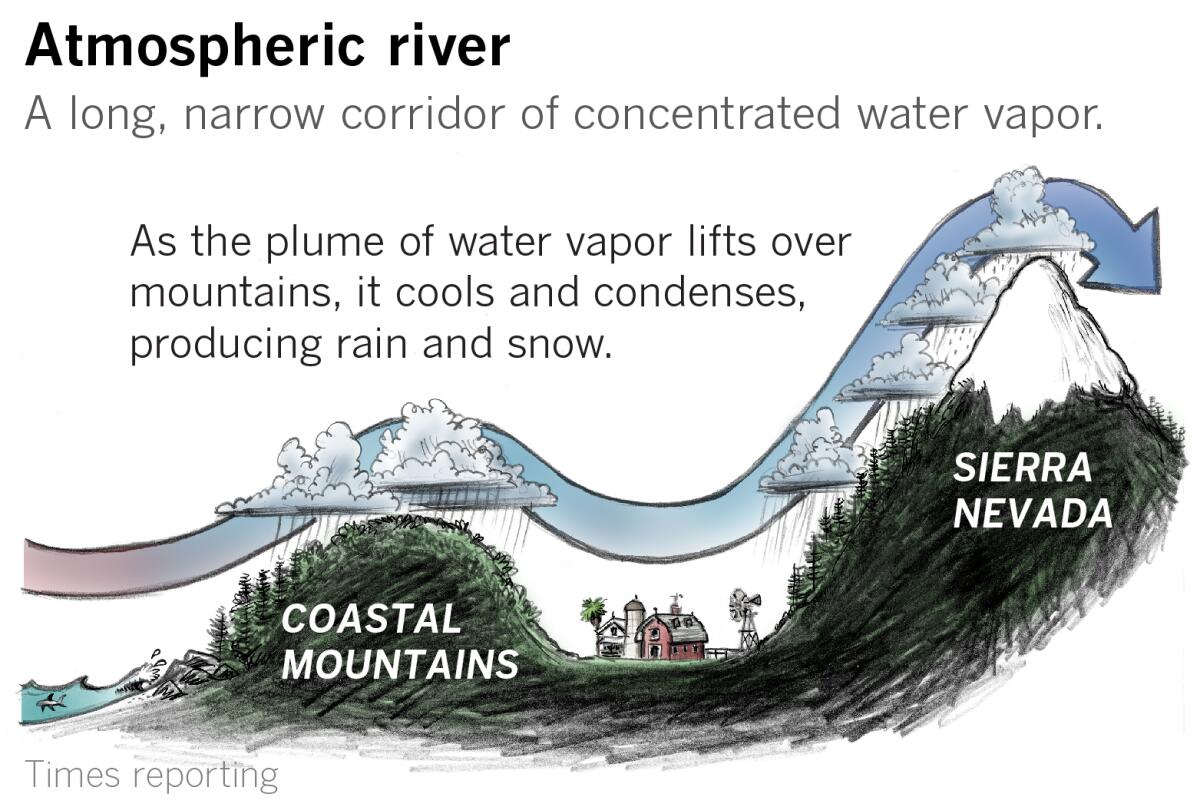

The 1962 storm also featured an atmospheric river, a phenomenon that accounts for as much as 50% of precipitation in the western United States. Atmospheric rivers are channels or corridors of water vapor, typically in the lowest 10,000 feet of the atmosphere. They average 300 to 400 miles wide, and can transport water at a rate per second equivalent to 25 Mississippi Rivers or 2.5 Amazon Rivers, according to Marty Ralph, an expert at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

An atmospheric river is sometimes called a “pineapple express.” However, although “all pineapple expresses are atmospheric rivers, not all atmospheric rivers are pineapple expresses,” said Drew Peterson, a National Weather Service meteorologist in Monterey. Pineapple expresses are the warm atmospheric rivers that originate in the Pacific Ocean near Hawaii.

The recent storms were the result of unusually deep low pressure off the Pacific Northwest coast. “The low is a driver to strengthen the atmospheric river,” said Tardy, the San Diego meteorologist. “Two things you need are deep water vapor moisture in the atmosphere, and you need a strong wind field to make a significant atmospheric river. The atmospheric river needs wind transport in the Pacific; otherwise, it’s just moisture.”

The pressure gradient — the difference between high- and low-pressure areas — also drives the winds.

There is plenty of moisture in the South Pacific, Tardy explained, and the typhoon remnants are not necessarily needed to produce heavy rain events, atmospheric rivers or the version of them called the pineapple express. A bomb cyclone in the Pacific Northwest was also not required for a heavy rain event, he said, but when everything comes together, this is what happens.

All of this is something that is very unusual to see at this latitude at this time of year, Tardy said.

Strong winds on the back side of the low buffeted towns on California’s North Coast on Sunday, said Ryan Aylward, a meteorologist with the National Weather Service’s office in Eureka. Counterclockwise circulation around the low-pressure system means that as the storm moves, as this one did off the coast, winds switch around from the south to the west, then the northwest. A lot of trees and utility poles were downed along California’s North Coast, according to Aylward. Sunday’s powerful storm churned offshore, 200 miles west of Seattle, but he said the 1962 storm tracked much closer to the coast and its winds did far more damage. That storm eventually came ashore on Vancouver Island.

The 1962 storm also caused major flooding and mudslides, especially in the Bay Area. Oakland received 4.52 inches of rain in one day, and Sacramento got 3.77 inches. Wind damage was widespread from Oregon to British Columbia.

In Sunday’s storm, downtown Sacramento racked up a record 5.44 inches in a 24-hour period, shattering a record set in 1880, according to the National Weather Service. Blue Canyon, off Interstate 80 in the Sierra Nevada northeast of Sacramento, got 10.4 inches of rain, also breaking a record.

This year’s storms were unusual for October, but they also were providential. Because the ground was so dry, due to extended drought, it absorbed the precipitation like a dry sponge. Reservoirs had plenty of capacity to capture the rainfall. Had this not been the case, there would have been more widespread flooding, Aylward noted. “We’re lucky this happened in October.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.