Wrenching struggle to define critical race theory divides an Orange County school district

- Share via

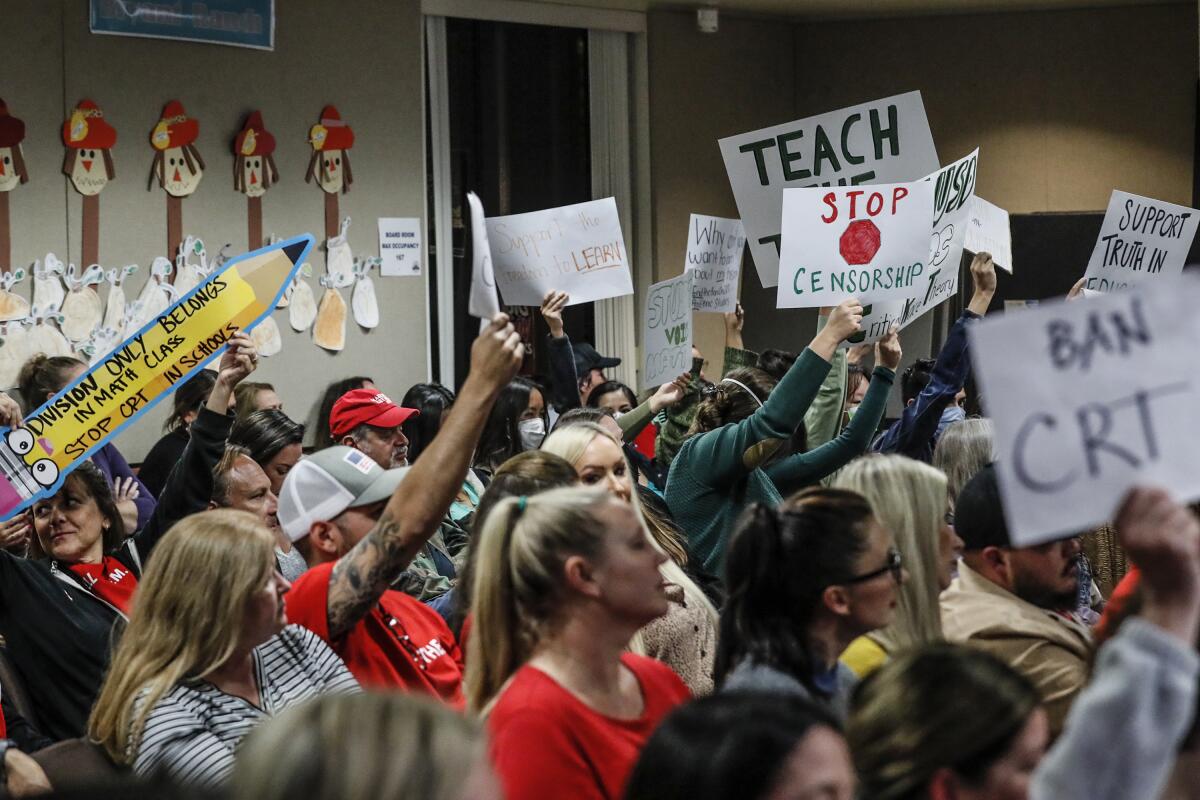

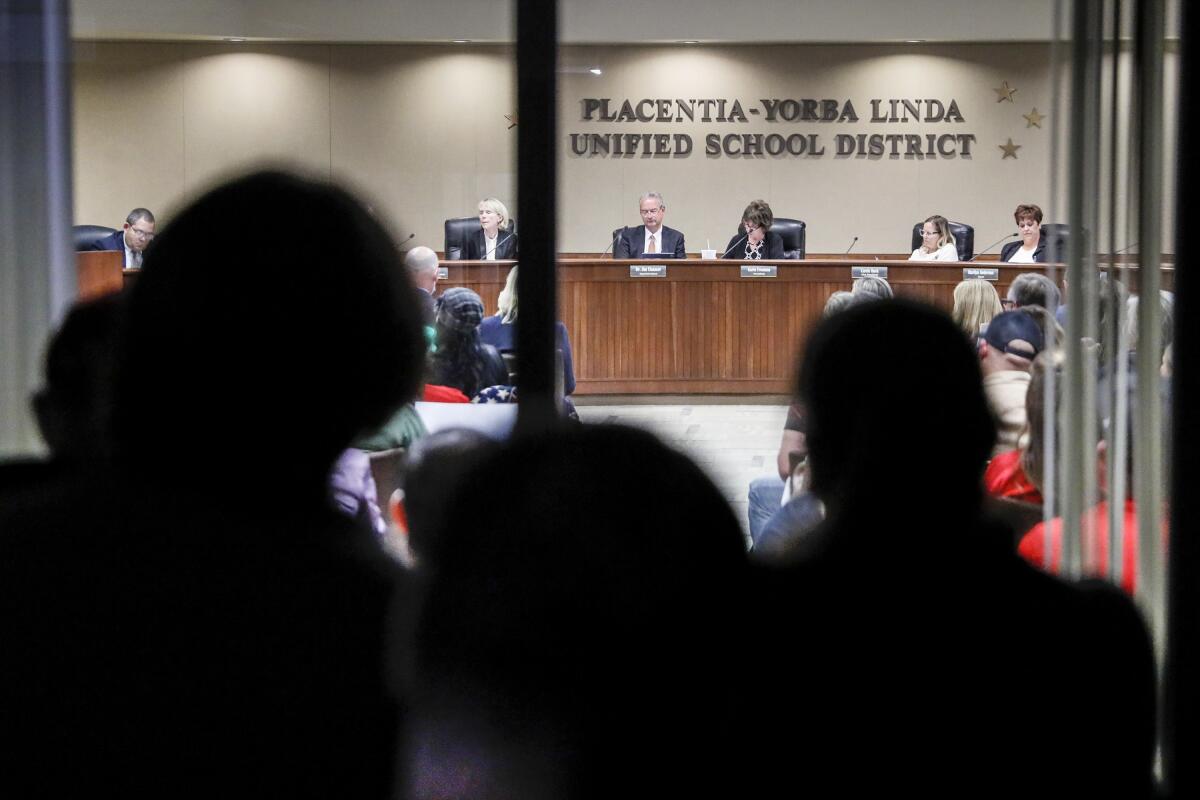

Inside a wood-clad meeting room in Orange County, five school board members sat before a sign-waving, opinionated crowd. For more than three hours, the trustees listened, debated and asked questions as they tried to decide whether to ban classroom teaching on a hard-to-define topic not taught in their schools: critical race theory.

The board members of the Placentia-Yorba Linda Unified School District had even turned to the trusted pages of the Encyclopedia Britannica, copying the entry for critical race theory into a public resolution that could become the legal policy of the district.

“I don’t think that this definition is really good,” trustee Marilyn Anderson said after reading the dense entry. “I think it needs to be really specific. It needs to spell out the specific theories that we do not want taught in our district — like that the United States is fundamentally or systemically racist.”

At the end of a long night, the board postponed the vote. But what emerged during their session revealed far more than angst over a “yes” or “no” vote on whether to ban critical race theory. Their meeting offered an up-close look at how an advanced academic concept has been transformed into a politicized slogan framing uncomfortable discussions about how to teach race, racism and equity in schools — and how the quest to define it inside a suburban school board meeting can be a minefield.

Ethnic studies is now required for future graduating California high school students. A look inside what students talk about in ethnic studies classes.

Critical race theory is a university-level academic lens for examining how racial inequality and racism are historically embedded in legal systems, policies and institutions in America and is not generally taught in K-12 schools. Yet Republicans have seized on it as a wedge issue painting white people as racist oppressors and people of color as the oppressed. Democrats largely see the conservative drive against critical race theory as racist dog-whistle politics that polarizes broader discussions about reckoning with America’s past.

Against this backdrop, school board members and parents in suburban Placentia-Yorba Linda are trying to figure it all out for their kids.

Although ultimately designed to ban critical race theory, the district’s 14-point resolution was touted as a way to foster a “safe and respectful environment for students.” It said the district “stands by the commitment to teach a complete and accurate account of history while also supporting the cultural integrity of students.”

Among the issues considered during the discussion were whether the district should promote “equity” or “equality”; whether to include the word “multiculturalism”; and whether it was appropriate to strive to “free students from the historical transgressions of the past.”

California’s top education policy making body voted Thursday to adopt a model curriculum in ethnic studies, ending a years-long and tortuous debate over the content and place of such coursework in public education in the state.

The public comments at the meeting were nearly evenly split between those in favor and those opposed to what they believed critical race theory stands for. The vast majority of students who spoke, including students of color, opposed the ban and supported their ethnic studies class, currently an elective course in high school.

“I have learned that people like me can make history — something I never thought I would be able to learn within the American education system,” one student told the board.

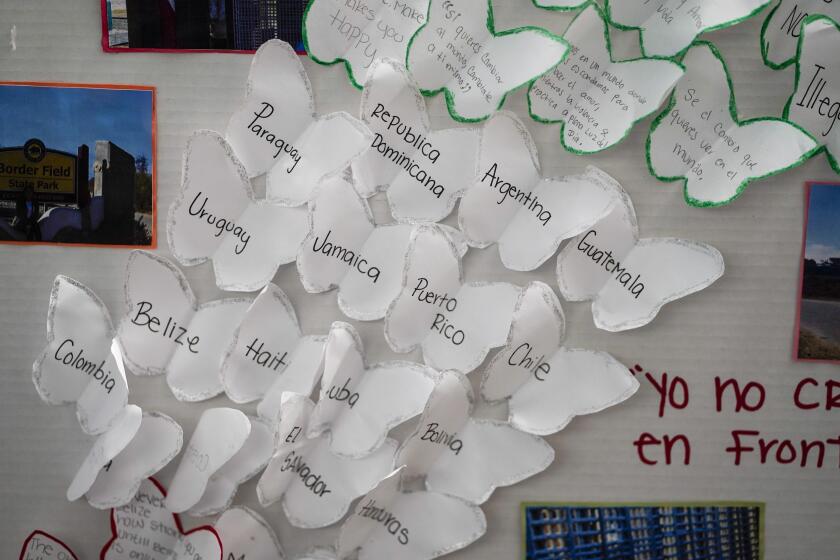

Critical race theory often becomes mixed up with ethnic studies, a different academic discipline that seeks to guide students in both K-12 and college courses through the histories, struggles and contributions of Black, Latino, Asian and Indigenous Americans. Earlier this year, California became the first state in the nation to make ethnic studies a course requirement for high school graduation in 2030 — and educators in each district can design their course with guidance from a state-approved framework.

In September, Placentia-Yorba Linda made headlines when a Yorba Linda High School student held a handmade poster reading “Ur dad is my gardener” before a football game against a high school with a more sizable Latino student population. About 44% of Placentia-Yorba Linda’s 23,000 students are Hispanic or Latino and 31% white, the two largest populations. Some in the community pointed to the incident as an urgent call for more education around diversity and anti-racism.

The school board narrowly approved the development of its current ethnic studies elective earlier this year. It also approved a resolution condemning racism in 2020.

In school board races around the country, activists are running against critical race theory.

It’s unclear what the board will decide to do about critical race theory. Some trustees, including Anderson, Leandra Blades and Shawn Youngblood, have been vocal about their opposition to it. Blades has also been criticized for attending the Jan. 6 Trump rally in Washington, D.C.

The tenor of the meeting was at times sharp, but civil. Some attendees applauded for those who agreed with them and murmured disapproval for those who did not. Board members volleyed over several terms, including a point in the resolution that promoted “honoring the experiences of all students by encouraging instruction that appropriately explores multiculturalism.”

Anderson asked if the word “multiculturalism” could be replaced with the phrase, “the history, philosophy and structures which comprise the American experience.”

Board President Karin Freeman said multiculturalism was a logical term because it will be included in the title of the ethnic studies elective, but tentatively agreed to the substitution.

“Equity” and “equality” were also on the table as the board discussed whether to use one or both terms. Some argued that achieving equity was possible, but that true equality was harder to obtain.

The board ultimately decided to insert both words and wait for their attorneys to weigh in.

But defining critical race theory remained a centerpiece of conversation. The lengthy encyclopedia entry used in the draft describes it as “an intellectual and social movement and loosely organized framework of legal analysis based on the premise that race is not a natural, biologically grounded feature of physically distinct subgroups of human beings but a socially constructed (culturally invented) category that is used to oppress and exploit people of color.”

Youngblood, too, said they should spell out the specific components they oppose — including any curriculum material promoting or endorsing ideas such as “white supremacy,” “privilege,” “microaggressions,” or “anything that’s going to disparage one particular race.”

Blades agreed, and said that in lieu of the encyclopedia definition they should instead add bullet points about what won’t be taught, and how they “won’t be pitting the races against each other.”

In one respectful exchange, they discussed hypothetical situations that could careen into the classroom.

Board Vice President Carrie Buck worried that the proposed limitations could hinder discussions and foster confusion. She gave an example of a guest speaker who talked to students about her experiences as a woman of color. Buck wondered whether that conversation would be off-limits in the future because it touches on intersectionality, or the overlapping of social identities.

“I wouldn’t think we would be eliminating that,” Youngblood said. “I would think if it was a woman, a person of color, that came in and is talking about her success ... “

Buck interjected: “But what if she talks about the downfalls before she gets to success? Is that OK?”

“That’s absolutely OK,” Youngblood responded, “but I think where it gets to be problematic is to say, ‘I had to do this and all the whites were keeping me down, and there was no way in which I could do it because the whole system is racist.’ That would be wrong.”

Opponents say the coursework sows divisions, but experts say it’s necessary for overcoming them.

Raquel Fleischman, a mother of three students in the district, said she was concerned by the ambiguity of the proposed ban. She worried that the resolution was so vague that any mention of — or questions surrounding — race could potentially fall under its umbrella of exclusion.

“There’s so much left up in the air about what it even is,” Fleischman said before the meeting. “If we can’t even come to an agreement about what it is, then how can we ban it? In general, there aren’t many resolutions to ban anything in teaching.”

One father, Miguel Lopez, emphasized that critical race theory is not being taught in the district at any level, but has instead become “this catchall that is all-encompassing when we talk about issues of race in this country.”

“It has this chilling effect — not just here in this district, but across the country — where things that we’re trying to discuss, that we need to discuss, regarding race and racism, are just not being taught,” he said.

But others were strongly opposed to critical race theory, and urged the board to approve the resolution on the table. Some threatened to pull their kids from the district lest they become “indoctrinated.”

“By separating children by race — and insinuating that some are holding others back by perpetuating some sort of systemic racism — doesn’t this create division and hatred?” asked Jan Templin. “I don’t think it creates friends.”

Another, who gave her name as Amy S., said critical race theory “perpetuates the victim mindset,” and worried that the teachings implied that white children should be discriminated against in order to make up for mistakes of the past.

Critical race theory has become a lightning rod for Republicans as they seek to prevent schools from teaching or promoting it.

The resolution is back on the drafting table and likely to return in December or January, officials said.

Theresa Montaño, a professor of Chicana and Chicano Studies at Cal State Northridge who helped craft an early draft of the state’s ethnic studies curriculum, was not surprised to hear that officials couldn’t settle on a definition of critical race theory. School boards looking to ban the concept are often “responding to a body politic that’s attacking critical race theory, but they have no knowledge of what it is,” she said. “Bans have become a means to “attack some of the civil rights gains like ethnic studies, like anti-racist education.”

“You have to look at the underlying messaging and underlying concepts that [these boards] are really trying to negotiate,” Montaño said.

Board members in Placentia-Yorba Linda did not respond to requests for comment.

During the meeting, retired teacher and district administrator Nancy Watkins told the board that critical race theory has been “emptied of meaning,” and is being used as a placeholder for many issues relating to equity, social justice and even politics.

“This resolution attempts to take a complex issue that few people understand, define it with an Encyclopedia Britannica definition, and create two polar bad options: We either ban CRT or we teach CRT,” she said. “The truth is not reflected in either of those extreme choices.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.