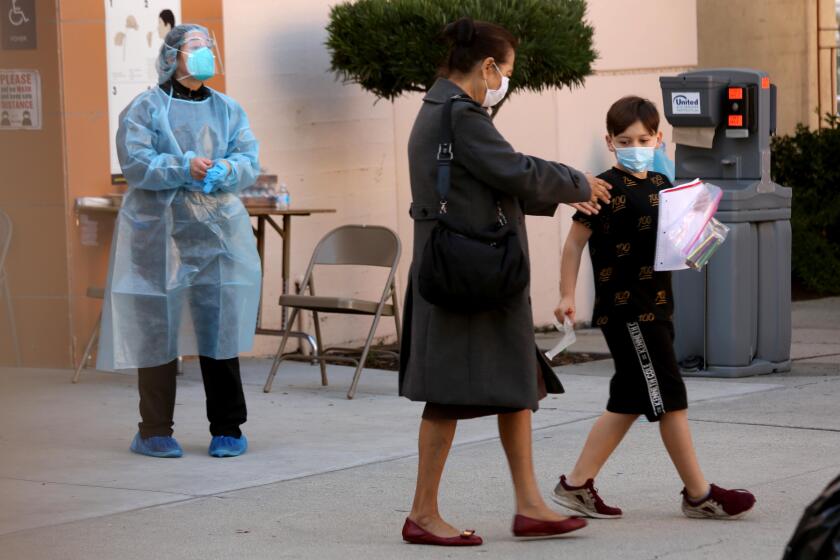

Despite Omicron, L.A. sees far fewer critically ill patients than last winter

- Share via

Despite an unprecedented spike in cases fueled by the Omicron variant, Los Angeles County hospitals are seeing far fewer critically ill coronavirus-positive patients than they did last winter.

Officials emphasize that the healthcare system still faces serious challenges because so many people are becoming infected, and it’s unclear how close the Omicron wave is to peaking. Meanwhile, L.A. County ambulance services and hospitals are contending with coronavirus-related staffing shortages as more of their workers become infected.

But the early data here seem to reflect the experience elsewhere — that Omicron, while far more transmissible than the previously dominant Delta variant, tends to cause less severe symptoms, especially in those who have been vaccinated and boosted.

“This is very different than what we were experiencing a year ago,” Dr. Brad Spellberg, chief medical officer at Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center, said Friday. “Clearly, the number of positive tests is actually higher than it was a year ago — and I understand why that’s very scary, in terms of these numbers going up — but the average sickness level is substantially lower.”

L.A. County reported 37,215 new COVID-19 infections on Thursday and has recorded more than 174,000 new cases since New Year’s Eve.

This week marked the one-year anniversary of the most difficult period of the pandemic in L.A. County, when the number of COVID-19 patients hospitalized soared to an all-time high of 8,098, on Jan. 5, 2021. The number of people in intensive care peaked three days later at 1,731, at a time when hospital morgues were overflowing.

As of Thursday, there were 2,902 coronavirus-positive patients in L.A. County hospitals, including 391 in intensive care. While hospital admissions are still trending upward, there are other signs that the Omicron wave will look different from those that came before.

The number of people admitted to hospitals in L.A. County for all reasons — COVID-19 and otherwise — has actually remained stable recently, hovering around 13,000, according to data presented by Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer. During last winter’s surge, more than 16,000 people were hospitalized for all reasons.

“Now, this can change, obviously. Hospitalizations are a lagging indicator. And as cases go up, shortly afterward, we start seeing the increases in hospitalizations,” Ferrer said during a briefing Thursday. “But I do want to note that [this winter] we haven’t seen the same rise we saw at the beginning of the winter surge last year.”

California will extend its statewide mask mandate for indoor public spaces for another month as an unprecedented wave of coronavirus infections continues to wash over the state.

Even though the number of hospitalized patients testing positive for the coronavirus has risen quickly, COVID-19 patients are occupying a relatively low percentage of the county’s ICU beds. About 7% of L.A. County’s total staffed ICU beds are taken up by COVID-19 patients, compared with 15% during the summer Delta wave and more than 50% last winter.

In addition, many coronavirus-positive patients are seeking hospital care for non-COVID reasons, such as hip replacement, heart surgery or cancer treatment, Ferrer said, and their coronavirus diagnoses were confirmed only because hospitals require incoming patients to be tested.

In early November — before Omicron swept around the world, and Delta was still dominant — 75% of coronavirus-positive patients countywide were in the hospital for COVID-related medical issues, Ferrer said.

The rate of those testing positive in L.A. Unified is the highest of the pandemic. Officials insist schools will be safe.

By late December, the same was true for 45% of coronavirus-positive hospitalized patients, Ferrer estimated. That means a majority of coronavirus-positive patients “would likely have been hospitalized regardless,” said Ferrer. “When you’ve got a lot of community transmission, you’re going to have more people testing positive who are asymptomatic for COVID illness but in this case getting hospitalized for something else.”

During last winter’s COVID-19 surge, about 80% of coronavirus-positive patients in the emergency department at L.A. County-USC Medical Center were being admitted to the hospital, and nearly half of those went to the ICU, Spellberg said. Now, about a third of coronavirus-positive patients are admitted, and 20% to 25% are going to the ICU.

“That gives you a sense of the difference in magnitude,” he said. “This is why last year was much more stressful in many ways. We did come within a hairsbreadth of triaging patients last year.”

Still, it’s important to note that coronavirus-positive patients — regardless of why they’ve been admitted — are tricky to treat.

“People who test positive for COVID require resource-intensive, transmission-based precautions, including isolation rooms, cohorted staff and personal protective equipment, all of which add a particularly high burden,” Ferrer said.

Many schools are struggling to find staff. Many students are staying home. Test kits from the state are too few and often too late.

The fact that there are fewer critically ill COVID-19 patients is likely due to a number of factors, including the number of residents who are either vaccinated or have had prior exposure to the virus.

In L.A. County, 75% of residents of all ages have received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, and 67% are fully vaccinated. About one-quarter of the county’s residents have received a booster dose.

Another likely explanation is that Omicron appears to be less likely to infect the lungs. The variant is seemingly more contagious in the upper airways, which is of less concern for adults but can pose problems for children.

Employers in L.A. County will have to provide medical-grade masks, surgical masks or respirators to indoor employees in close contact with others.

While it is milder on the whole, Omicron is so contagious that staffing shortages are, at least in some places, worse now than they were in previous surges.

“We’re tight in the hospital not so much because of a flood of patients but because we have patients coming in and a bunch of beds closed,” Spellberg said.

This week, L.A. County Assistant Fire Chief Brian Bennett said ambulance companies were so hobbled by infections — with maybe half of their workforce unavailable for coronavirus-related reasons — that firefighters at times had to use firetrucks to transport patients.

“This is kind of unprecedented,” Bennett said in a briefing to the Carson City Council this week. For people with mild issues, firefighters are “encouraging the residents to either find a private vehicle or alternative methods to get to the hospital so that we can save those ambulances for the critical patients.”

The Los Angeles Fire Department is also seeing high numbers of firefighters unable to work due to the coronavirus, Chief Ralph Terrazas said at a briefing. As of Wednesday, 299 firefighters were unable to work; just a few weeks ago, there were 24, Terrazas said.

“It’s the highest we’ve seen at any one time,” Terrazas said of the department, which has nearly 3,800 workers. The department is canceling time off to maintain daily staffing, he added.

L.A. County officials say 911 response times have worsened, and ambulances are facing delays in dropping off patients at hospitals.

Following a major spike in Omicron cases among Los Angeles’ public safety workers, city officials are hoping for an equally swift decline.

The Omicron variant, which now accounts for more than 85% of analyzed cases in L.A. County, is easily the most contagious coronavirus strain yet — two to four times as transmissible as Delta. And that’s infecting far more people simultaneously.

L.A. County on Friday reported 43,712 new coronavirus cases — the highest single-day total ever, breaking the record of 37,215 set the day before. During the peak of last winter’s surge, about 16,000 cases were being reported a day.

“If you have a ton of transmission like we have now, it affects everybody’s workforce. Everybody’s short-staffed … and certainly, hospitals and healthcare providers are facing staffing issues,” Ferrer said. “So that’s the real difference between what we have now and what we had, for example, when we had the Delta surge — where we actually had lots of patients who needed hospital care, but we didn’t have this raging rate of infection that was really making it super hard for there to be enough staff to care for people.”

Symptoms of common colds, the flu and COVID-19 can overlap, so experts say testing is the best way to determine which of those you have.

While breakthrough infections among vaccinated and boosted people are becoming more common because of Omicron, unvaccinated people are still far more likely to be infected. During the week that ended Dec. 25, unvaccinated county residents were four times more likely to report a coronavirus infection than vaccinated people who had gotten a booster.

That week, out of every 100,000 unvaccinated people in L.A. County, 991 were confirmed to have the coronavirus. For every 100,000 people who were fully vaccinated, but not boosted, there were 588 new cases. And for every 100,000 who had gotten a booster shot, there were 254 new cases.

Unvaccinated L.A. County residents were 38 times more likely to need hospitalization than boosted people and nine times more likely than those who were vaccinated but not boosted.

Case rates have risen dramatically among all racial and ethnic groups in L.A. County but are highest among Black residents. For the 14-day period to Dec. 30, there were 1,558 new coronavirus cases per 100,000 Black residents; 1,132 for white residents; 977 for Asian Americans and 947 for Latinos.

Holly Mitchell, chair of the L.A. County Board of Supervisors, said the high case rates among Black residents are reflective of the community’s lower vaccination rate.

“Hence, my insistence, my constant, vigilant encouragement for people to be vaccinated,” Mitchell said. “Getting vaccinated certainly will bring our numbers down in terms of hospitalization, severity of illness and, ultimately, death.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.