L.A. schools see coronavirus rates decline; student attendance improves amid record surge

- Share via

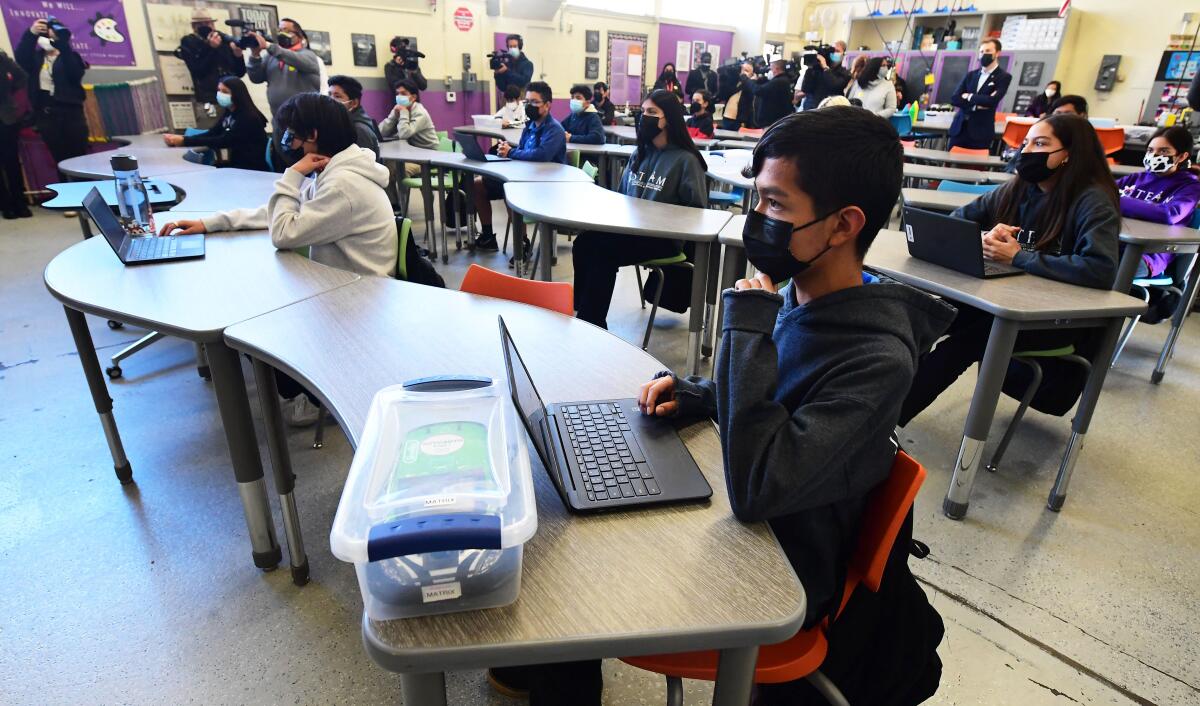

Campuses in the Los Angeles school district have lower coronavirus rates and improved attendance in their second week since returning from winter break. But infections remain near record levels, and the extent of exposure to the virus at school is difficult to determine because health officials have temporarily abandoned contact tracing, calling it too burdensome to mandate during the explosive surge.

Senior administrators said they are encouraged by the numbers, which come amid signs that cases from the Omicron variant could be peaking.

Since school started Jan. 11, L.A. school officials recorded an infection rate among students tested of 10%. This compares with a rate of 17% during baseline testing conducted from Jan. 3 through Jan. 10, before the start of school. The last week of school before winter break — when the Omicron surge already was pushing up numbers — the student infection rate was 0.22%.

Put another way, in testing during the week that ended Dec. 17, about 2 students in 1,000 tested positive. In early January baseline testing, just before school restarted, about 170 students per 1,000 tested positive. And since school started, about 100 students per 1,000 tested positive.

School officials interpreted the data as evidence that schools are safe and that students should be in class.

“Our schools are the safest-possible environments for our students and employees,” district officials posted on social media Wednesday. “We know that children thrive best when learning in person amongst their peers. While COVID-19 may be here to stay, Los Angeles Unified will continue to be nimble, resilient and responsive to the changing conditions of the pandemic.”

Attendance rates this week have improved significantly from last week, although they are still well below normal. About 34% of students were not in class the first week. On Tuesday, that figure was 28%. On Wednesday, it was 24%. Many students who tested positive in the week before school could be back in class — as could some students who were being held at home last week by worried parents.

And while schools remain open and functional, it hasn’t been easy.

“We are just drowning,” said one San Fernando Valley middle school teacher who requested anonymity for herself and for her school because, she said, she admires her administrators and believes they are doing the best they can.

Each of her five classes Thursday had about a third or more students out. In one period, 23 of 43 were absent.

“And it’s a different random group of students every day,” she said.

Her job includes covering classes for a teacher who quit after last semester. The replacement can’t be processed because the people involved have been deployed to help at campuses.

The school’s administrative team is trying to contact trace, she said, but is overwhelmed: “I along with several other teachers — if we have not gotten COVID — are feeling like we will get it at school by the end of the month.”

Schools remain comparatively safe because of extensive protocols, said Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, a professor of medicine and infectious-disease specialist at UC San Francisco.

“You have to assume that a high proportion of folks have it,” he said of the Omicron variant. “But I think what we’ve learned throughout the pandemic, when things were a little bit less chaotic, is that the school is actually a very controlled environment, compared to milling around in an amusement park or a game center or the mall or something like that.”

Three new outbreak investigations are focused on L.A. Unified schools — at 102nd Street Early Education Center in Watts, Whitney Young Continuation High School in Hyde Park and 52nd Street Elementary in Vermont Square. An outbreak is when there are three or more cases of infection within a 14-day period linked to each other by contact in school.

This magnitude of outbreaks is about the same as in the fall, possibly suggesting that schools are effectively containing the spread of the virus on campus. It’s hard to be certain, however, because the high number of cases has made contact tracing difficult — and both state and county health officials have told schools they can discard the effort during the current surge. That means a school-based outbreak might not be identified at all.

Under a currently active “surge protocol,” schools are no longer required to notify the county “of persons on campus who were exposed to the infected person during the infectious period.”

Such information had previously been used to identify outbreaks on campus. But how would one carry out such a painstaking process, for example, at Banning Senior High School in Wilmington, which has 328 active cases, according to an L.A. Times school coronavirus data tracker?

“It’s impossible,” Chin-Hong said.

“There aren’t the resources to do contact tracing properly in the Omicron wave — anywhere,” said Dr. Eric Topol, professor and executive vice president of Scripps Research, based in La Jolla.

By any standard, the Omicron surge has rewritten the record books for coronavirus infections found among students.

For a week in mid-November, for example, when health officials still were dealing with the Delta variant surge, the number of students with positive tests in L.A. Unified was 612. This baseline testing found 62,704 infected students — who had to stay home until cleared for return — out of an enrollment of about 450,000. Since classes resumed, 49,211 students have tested positive. And these were, by and large, students who had just been cleared to attend school in the baseline testing the week before.

The staff infection rate for the week ending Jan. 16 was 12.8%, signaling the ongoing struggle both in L.A. Unified and across the nation to maintain classroom learning. The number of staff cases last week — including among people who’d been cleared for work the previous week — was 4,282. This compares to 36 during a week in mid-November, when schools already were hard-pressed to fill vacancies and dealing with a shortage of substitute teachers.

Determining those who were close contacts to an infected person during the Omicron surge has become increasingly difficult, but L.A. Unified has tried. Last week, the figures were 855 close contacts among staff and 24,073 among students. Under prior district policy, all of these contacts would have had to remain home for as much as two weeks. Under revised policy, the vast majority have been able to remain on campus, although the district did not release a specific breakdown.

Revised district policies allow exposed individuals to remain on campus provided they continue to test negative, have no symptoms and were following safety protocols at the time of the exposure.

But the rules are complicated and have evolved rapidly over time, making it difficult for principals, who have to play the role of local health czar.

Elaine Haber’s family went through a round of COVID-19 but managed to keep it from their daughter Lucy, a third-grader at Clover Avenue Elementary School in Palms. School staffers were concerned about her daughter’s stuffy nose and classified her as an “active” COVID-19 case, requiring her to isolate at home. But Lucy repeatedly tested negative, including three times on the district’s precise PCR tests, Haber said, and she suffers from allergies, which was attested to in writing by the family doctor.

The school, which consulted with some district higher-ups, did not budge until an inquiry from The Times spurred a review by senior staff. The district has apologized to Haber and authorized Lucy to return to school.

During the first week of school, about half of the 130,000 student absences were accounted for by those who tested positive for the coronavirus in the week before the start of the term. Others may have tested positive or had symptoms, but the information was not uploaded to the district’s health-screening system.

There was no estimate regarding how many families chose to keep students home out of caution, but enrollment has ticked upward in the remote-learning option called City of Angels, despite its problems.

L.A. Unified operates the largest school coronavirus testing program in the nation, with more than 500,000 mandatory tests administered every week for all students and staff. Countywide data on testing are driven largely by the L.A. Unified results, even though L.A. Unified accounts for about a third of county students. For example, from Jan. 3 through Jan. 9, L.A. Unified was responsible for 432,646 of the 547,466 tests — about 80% of the school-related tests.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.