- Share via

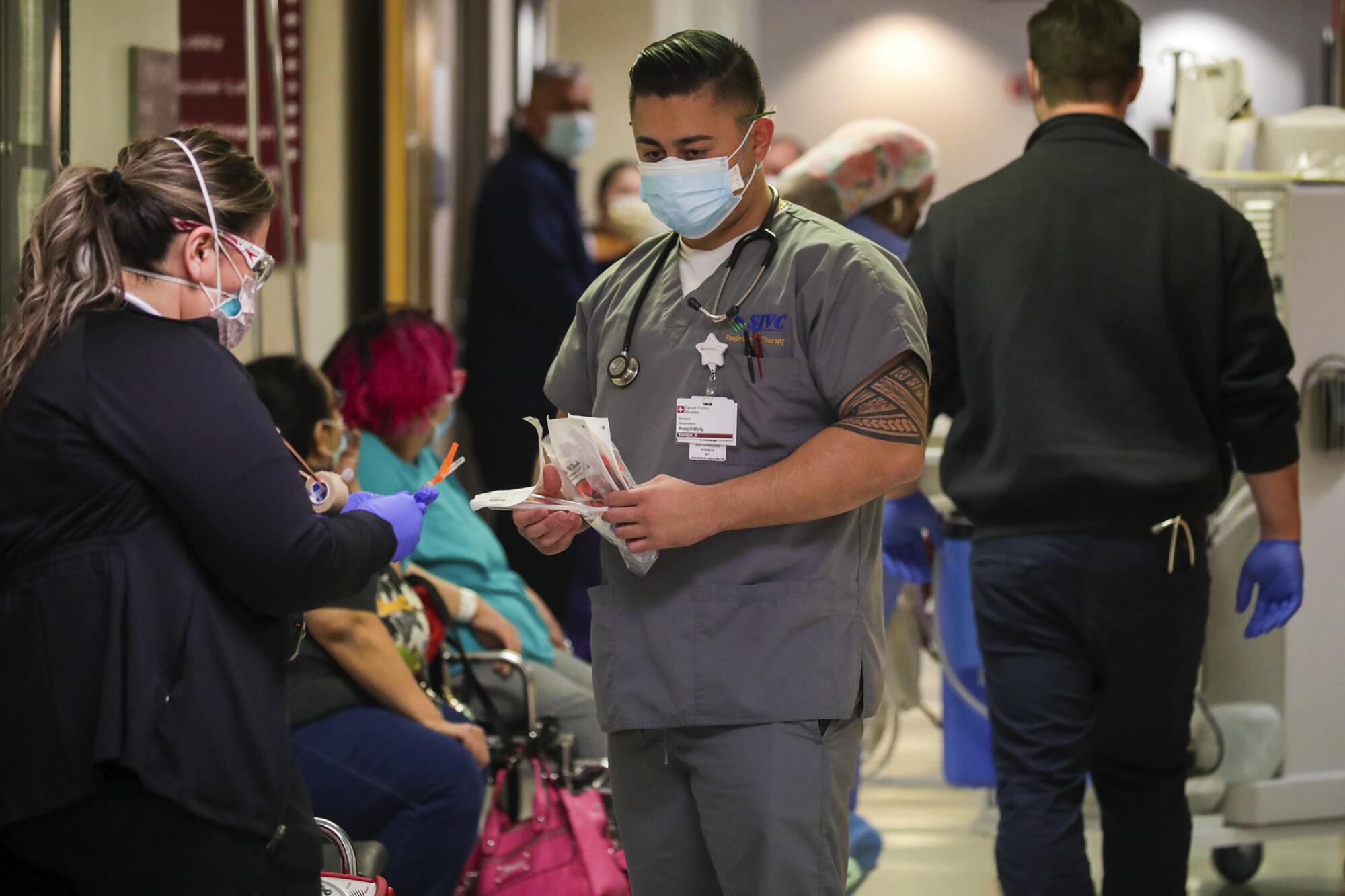

VICTORVILLE — The COVID-19 patients slumped in chairs in a hallway outside the emergency room of the Desert Valley Hospital in Victorville. There were no gurneys for them, no beds and no rooms.

Doctors and nurses dashed back and forth from the ER to treat them, dodging one another and medical equipment being wheeled about.

“This is not ideal for us,” said emergency room Dr. Leroy Pascal. “But we’re having to see patients wherever we can.”

Coronavirus transmission rates have been dropping in California in recent weeks, a sign that the surge spawned by the Omicron is easing.

But while the pandemic has been a series of ups and downs, the sheer longevity of it has become a nemesis of its own, making extended periods of relief an elusive commodity.

At Desert Valley Hospital, COVID-19 patients are still streaming into the hospital that is already well over capacity. Staffing shortages have contributed to fatigue as workers take on ever more patients.

It’s no mystery why this hospital in the Victor Valley is so hard hit: Only about half the population in this rural desert area of San Bernardino County is fully vaccinated, meaning they’ve received at least two doses, according to county data.

Many residents in the area also suffer from chronic diseases such as diabetes and high blood pressure, which increases their risk of developing severe COVID-19 and dying from it. The combination of unhealthy and unvaccinated is driving the surge.

Over the past week, 163 patients were crammed into the 148-bed hospital. About half of them were positive for COVID-19. Most were unvaccinated, according to hospital officials. The 24 ICU beds and 18 emergency room beds were mostly occupied by them too.

Dr. Imran Siddiqui, the chief medical officer of Desert Valley Hospital, said staffing is one of the most pressing issues he’s facing. The dozens of doctors, nurses and lab technicians that have become infected and forced to stay home have led to a staff shortage like those seen throughout the state in the Omicron surge.

Siddiqui said he has lost up to 80 staffers in one day during the surge. He said workers have become so exhausted they’ve declined to take the extra pay that comes with covering shifts. In order to lessen some of the workloads, he’s tried to help out by working 12-hour shifts and coming in every other weekend.

“Last year was about not having enough ventilators. This year it’s staffing,” he said. “I’m exhausted. Exhausted.”

The state has sent travel nurses to help. On a recent Thursday afternoon, Rebekah Seyler, 31, of Arkansas, was in the emergency room checking on a COVID-19 patient, a 78-year-old diabetic and unvaccinated woman who had to be intubated and put on a ventilator in an attempt to save her life.

Seyler said she was in Louisiana before coming to the desert, her first time in the Golden State. She arrived in late December, shortly after Christmas, when the surge was well underway.

“It’s been a little bit wild here for sure,” she said. “There’s more COVID patients.”

The Victor Valley region is dotted with small desert communities and a smattering that have boomed into larger towns, such as Victorville, Hesperia, Adelanto and Apple Valley. Together the four cities have a population of more than 340,000 residents, made up largely of low-income Latino, Black and white families.

More than a year ago, this region was hit hard by the fall and winter surge. Siddiqui said the difference between this surge and that one is that, then, there were enough workers to tackle the influx of sick patients coming in. A lot of people also chose not to visit the emergency room for non-COVID medical needs, allowing staff to focus purely on infected patients.

But that 2020 wave was still a profoundly difficult time for the hospital. Facing a tsunami of sick patients, doctors had to treat them not just in the hallways but outside in cars and ambulances.

Leading the charge was Dr. Peter Fischl, the chief surgeon at the hospital, whose medical experience stretches back to the presidency of Jimmy Carter. He was on the front lines of the AIDS epidemic and used some techniques from that earlier scourge to protect himself and his staff during the 2020 wave.

But his time in the trenches exposed him, and Fischl caught the virus, at a time it was particularly severe and no vaccines were available. His staff worried the 72-year-old might die.

His absence also created staffing issues. Fischl was the only full-time surgeon and was handling most of the surgeries at the hospital. Administrators said they had to depend on surgical independent contractors while Fischl recovered.

Antibody-drug treatments eased Fischl’s symptoms, and he gradually recovered. He returned to work in January 2021.

Since then, Fischl has been fully vaccinated and has not stopped working. He said helping patients has been his lifelong mission, and a way of honoring them for helping him grow when he was starting out as a surgeon.

“It’s my personal ethics,” he said. “I trained on them without them objecting to the fact that I was either a student or a resident taking care of them.”

On Thursday, shortly before 1 p.m., Fischl was inside the surgical room working on another patient. Not far away, more patients were coming into the emergency room.

Pascal, the ER director, made his way to the hallway to meet an 80-year-old COVID patient named Benjamin Garcia. The elderly man was coughing and felt weak. Sitting next to him was his grandson, Isaac Zapata, 24.

Zapata said his grandfather is active and often works on his 1969 Chevy Camaro in the driveway. But in the past two weeks he slowed down, and two days ago, his symptoms started to worsen.

Garcia tested positive for the coronavirus, and Zapata feared he had infected him. They live together.

“I’m vaccinated,” Zapata said. Garcia was not.

“He had a friend who got vaccinated and got sick,” Zapata said. “He never heard from him, so he got scared that maybe that could happen to him.”

After checking him out, Pascal told the pair they would continue to do tests and determine if he would be required to stay at the hospital.

“This is the kind of case we’re getting,” he said.

The patients continued to wait in the hallway, as the sick kept coming in.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.