Will COVID-19 long-haulers push outpatient medical system to breaking point?

Vaccination should temper the number and severity of persistent symptoms.

- Share via

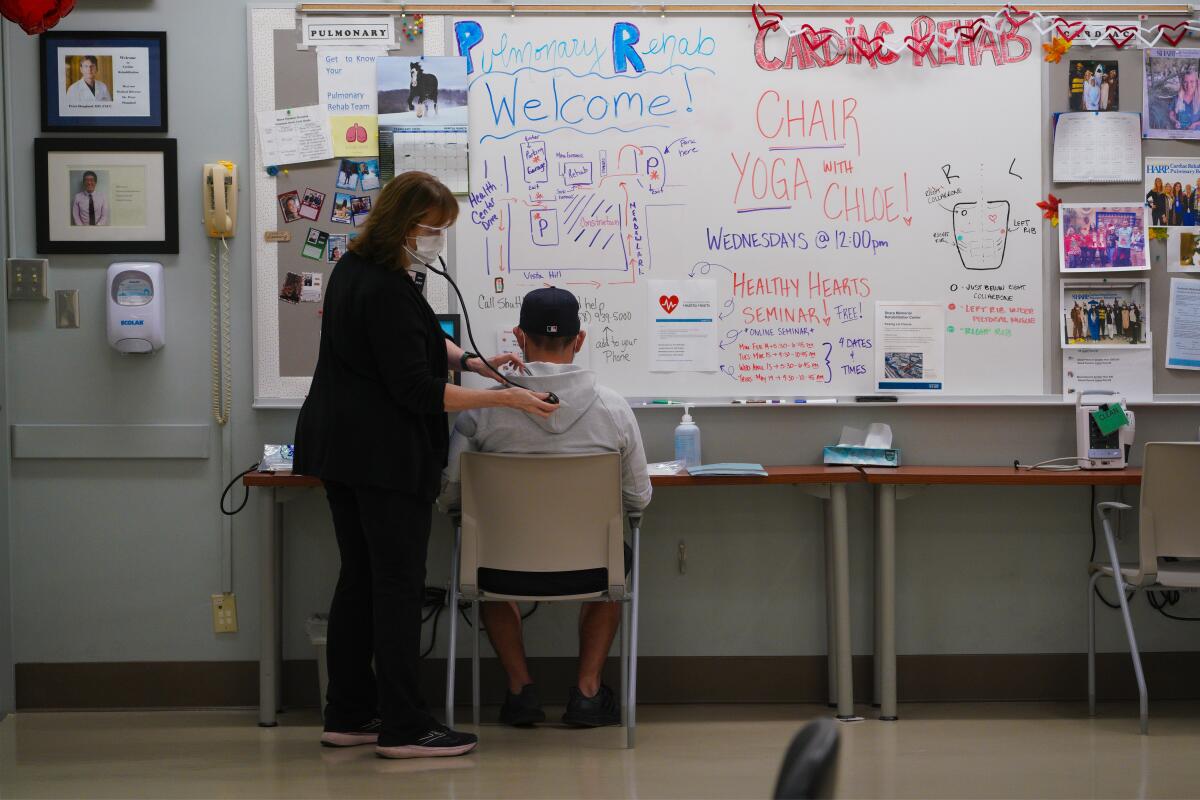

Carolina Nieto of Escondido and Julio Lara of Valley Center became the newest patients in the Sharp HealthCare COVID-19 recovery program on Friday, meeting with rehabilitation specialists about lingering symptoms they have suffered since 2021.

Nieto, 63, arrived pulling an oxygen tank more than a year after the virus put her in the hospital for 15 days. She continues to struggle with multiple COVID-19 symptoms, including short-term memory and exhaustion when she tries to walk more than a few steps at a time.

Lara, 42, said he has been unable to return to his active life. His scarred lungs, he said, have kept activities from surfing to snow boarding on hold, with severe fatigue making simple tasks like taking the trash to the curb draining even months after he got sick.

With symptoms persisting for more than three months after infection, both are experiencing what the world has dubbed long COVID, a state of continual illness that may not resolve for months or even years. Neither is a victim of the recent Omicron wave, with Nieto’s infection occurring in January 2021, when original strains of the virus were still driving the pandemic. Lara’s illness started in September, when the Delta variant was dominant.

Their visit to the San Diego recovery clinic last week illustrates an important point: Previous waves of illness continue to generate significant demand for healthcare services even as the Omicron surge abates.

It’s a daunting trend given that local records show more than 300,000 San Diego County residents have started showing symptoms or tested positive since Christmas Day. The question quickly becomes: If new long COVID cases are still surfacing from exposures that occurred as long as a year ago, will persistent Omicron symptoms push the outpatient medical system beyond the breaking point?

After all, previous long COVID estimates indicate that between 10% and 30% of all infections will show multiple symptoms that remain months after the original infection has resolved. Those 300,000 holiday infections, then, could be expected to generate somewhere between 30,000 and 90,000 long COVID cases.

But local experts believe previous estimates of long COVID’s prevalence, made when other viral variants held sway, are probably too high for the Omicron surge.

While the COVID post-holiday hangover is already being felt in doctor’s offices across the region and nation in the form of an increased demand for appointments, there is optimism that the demand will not grow as fierce as it might have with one of the previous variants.

The nature of Omicron itself, and the fact that a large proportion of the populace was vaccinated when the latest surge arrived, are the two key factors that have experts feeling hopeful.

There is a growing consensus in medical literature that the lower overall severity of illness caused by Omicron is likely to translate to fewer long COVID diagnoses. The hope is that a less-severe illness will correlate with less-severe lingering symptoms.

And research increasingly shows that those who are partially or fully vaccinated before they get infected have fewer long COVID symptoms than those who never got their shots.

A study of 1.2 million British residents published last month in the Lancet, a respected medical journal, found that the odds of having symptoms 28 days after infection were “approximately halved by having two vaccine doses.”

Another research write-up from a group of experts in Massachusetts shows clear gains even for those who were unvaccinated at the time of infection, said Dr. William Tseng, an internal medicine specialist and assistant area medical director for Kaiser Permanente San Diego.

After examining the medical records of more than 240,000 people who tested positive, the researchers found that those who received at least one dose before infection had seven to 10 times lower odds of reporting two or more lingering COVID symptoms, compared with unvaccinated patients.

And those better odds also seem to extend to those who get vaccinated even after they start their recovery.

“You’re about four to six times less likely to experience long COVID if you vaccinate within four weeks, and even if you do it from four to eight weeks, you’re three times less likely,” Tseng said.

There is also growing evidence that for some who had severe illness, the vaccine can serve as some sort of immunological reset button. That was certainly the case for Nieto.

While vaccines were not widely available when she got sick in January 2021, she started her shot sequence in April of that year at a time when she felt miserable.

“The first vaccine made me feel so much better,” she said. “I used to shake a lot, and that went away like the day after I got my first dose.

“My shortness of breath was really bad. I couldn’t be without oxygen for even one second. It’s still not perfect. I still need oxygen when I walk, but it has been so much better since I got the vaccine.”

Lara said he and his family were unvaccinated when they went to a concert in Las Vegas in September. Coming home, he wasn’t feeling well. A 10-day hospital stay on high-dose oxygen followed, and he later learned that his lungs showed pulmonary fibrosis, a condition caused by scarred lung tissue. Today, he said, his doctors say he has permanently lost about 30% of his total lung capacity.

Now dedicated to preserving what’s left, the father, husband and business owner said he has not yet decided to get vaccinated. His focus for the time being, he said, will be on rehabilitation, especially the breathing exercises he hopes will restore his ability to exercise at a pace somewhere close to what he was able to do before getting sick.

Spotty test results — there were four negatives before he tested positive — and the swirling political maelstrom surrounding the vaccine, he added, have left him skeptical about vaccination.

“At this point, the damage is already done,” he said. “The vaccine’s not going to help me get my lungs back to where they were.”

Experts would counter that natural immunity earned by winning a bout with COVID wanes over time and that there is increasing evidence of reinfection, especially in places where Omicron has caused cases to surge.

Though vaccination seems capable of reducing the Omicron-related long COVID burden, local physicians say they believe the sheer number of cases that occurred in such a short period of time are still capable of straining an already-overwhelmed healthcare system.

Dr. Lucy Horton, a UC San Diego infectious disease specialist who manages the university’s long COVID clinic, said infection is particularly difficult for those with chronic diseases and conditions. For example, it’s often more difficult for diabetics to control their blood sugar levels. Migraines may come more often. Previously mild asthma may intensify.

These factors are likely to make Omicron’s presence felt despite the advantage of a population that was vaccinated when it arrived.

“I’m somewhat optimistic that the numbers will be a little bit lower because of that,” Horton said. “However, just because of the sheer number of cases that have occurred recently, even 5% would be significant.”

Dr. Abisola Olulade, a family medicine practitioner working in Sharp’s COVID recovery program, agreed.

“Anecdotally, in my practice, I am seeing more people present with long-term symptoms; I definitely have seen over the last, I would say, four to eight weeks since Omicron started,” Olulade.

Those symptoms, plus brain fog, added Dr. Bradley Patay, medical director of the COVID Recovery Program at Scripps Clinic in Torrey Pines, are the most common of the long symptoms. Brain fog, often described as an inability to focus or concentrate and a tendency toward forgetfulness, has so far been the most difficult to vanquish through therapy.

Some, he said, struggle to hold, manipulate and act on ideas, an especially distressing condition for the large number of local residents engaged in science careers.

Techniques like writing ideas down can help clear the fog, but progress is slow. Part of the issue is the crushing amount of anxiety that comes with being stuck in a mind haze that impedes a person’s ability to return to their previous levels of productivity.

“The brain takes longer to heal,” he said. “That’s almost one of the last things that improves in the patients I’m seeing.”

Though getting vaccinated helped clear things up, Nieto said she continues to experience some fogginess.

“When I’m talking, I forget words whether it’s in English or Spanish,” she said. “I want to say something, and I don’t get the words I wanted to say. It’s like having an incomplete conversation.”

Getting off oxygen and further clearing away COVID’s mental effects, she said, are her main hopes for therapy.

But both she and Lara said they also wished for a broader recognition of long COVID in the community and the overall healthcare system.

After spending time in the hospital, both said they were discharged and struggled to get follow-up appointments with specialists. Referrals to rehab programs took a long time. In the community, few seem to be talking about symptoms that last forever.

“They’re just not talking about the long-haulers a lot anymore,” Nieto said. “Somehow, we are being forgotten.”

“You know there are so many other people going through this, but you feel kind of alone,” Lara added. “You’re kind of on your own trying to figure out what you need to do next to get better.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.