California State Bar, under scrutiny for Tom Girardi scandal, gives director $43,000 raise

- Share via

The State Bar of California, under scrutiny for long-standing failures in protecting the public from Tom Girardi and other unscrupulous lawyers, this week gave its executive director a raise of nearly $43,000.

The pay hike brought Leah T. Wilson’s annual salary to $344,000, an amount that dwarfs the salaries of Gov. Gavin Newsom ($218,556) and other prominent government officials overseeing larger organizations, including the state attorney general ($189,841) and California’s recently named chief justice ($293,286).

The 14% bump for Wilson was triggered by the hiring this month of another highly compensated official at the public agency, General Counsel Ellin Davtyan, at a salary of $328,000. The terms of Wilson’s contract provide for her to make at least 5% more than her most-well-paid colleague, forcing the bar Monday to increase her pay as executive director by $42,737.

Agency representatives defended the salaries as necessary given inflation and the compensation that experienced attorneys like Wilson and Davtyan might command in the private sector.

“It’s a competitive marketplace for lawyers,” said Ruben Duran, a San Bernardino County attorney who chairs the state bar’s governing board. He said comparisons to the salaries of the governor and others are unfair. “I don’t want to go so far as to say apples and oranges, but it is a very specific type of role we’re filling.”

Others familiar with the pay of state workers are unconvinced.

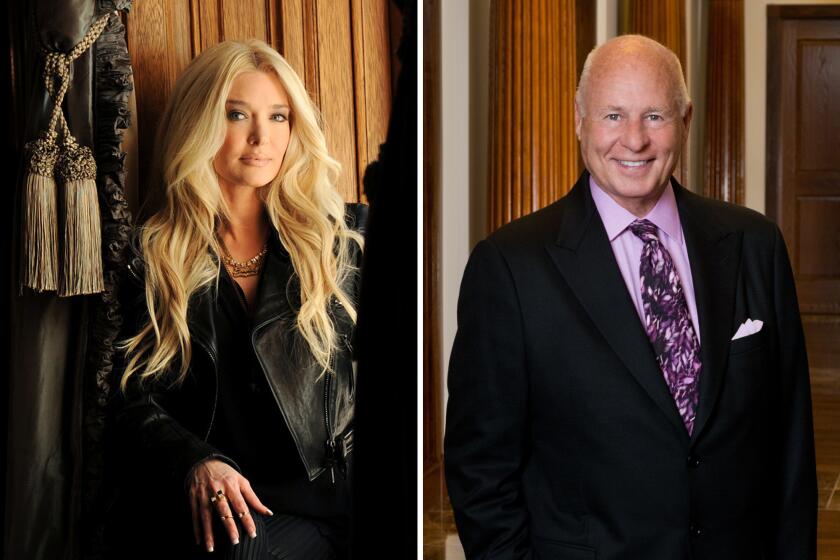

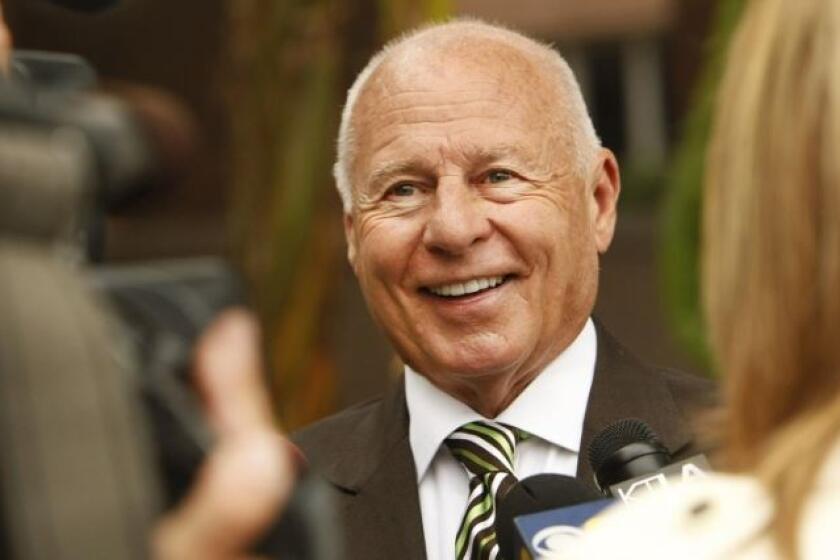

Tom Girardi is facing the collapse of everything he holds dear: his law firm, marriage to Erika Girardi, and reputation as a champion for the downtrodden.

“I don’t buy it,” said Michael Genest, who served as finance director for Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. He said he had known many talented government attorneys who put in long hours for more modest salaries because they believed in the mission and in what Gov. Jerry Brown once called the “psychic income” of public service. “These guys were fantastic lawyers, and they were making regular civil-service salaries.”

In Sacramento, lawmakers were already questioning agency pay generally when the new salaries took effect. The bar must go to the Legislature every year for approval of its annual fee assessment on attorneys, a measure that largely determines its revenue. On Tuesday, the Assembly approved a fee for 2023 of $390 per active attorney.

An analysis produced before the final vote noted the compensation of Wilson and Davtyan as part of a long history of “disproportionately high” pay at the bar.

“It is anticipated that these significant pay increases will ripple through other State Bar executive staff, increasing the already wide pay differential between the Bar and other state agencies,” the analysis stated.

The bar, the largest in the country, licenses California’s 260,000 attorneys and is supposed to investigate and discipline lawyers who cheat clients or engage in other types of misconduct. In the wake of Girardi’s spectacular downfall, amid evidence he misappropriated millions in settlement money, critics have lambasted the agency for bungling complaints against him.

After a Times report last year about the legendary lawyer’s cultivation of bar officials, the agency conducted its own audit, which found “mistakes made in some investigations over the many decades of Mr. Girardi’s career going back some 40 years.” A separate audit ordered by legislators found systemic shortcomings, with lawyers avoiding public accountability despite lengthy records of misconduct complaints. Currently, a law firm hired by the bar is investigating whether officials within the agency helped Girardi elude punishment.

The bar has pledged to reform itself; Duran, the board chair, said Wilson’s role as executive director is key to those efforts. Wilson began working at the bar in 2015, served as executive director from 2017 until 2020 and served as a paid consultant for the agency until last summer, when she returned to the executive director’s post.

Top bar executives in some other states make less than their California counterpart, though their agencies are smaller than the 610-person State Bar of California, and the cost of living is often lower than in San Francisco and L.A., where the agency has offices. In Florida, for example, with about 278 employees, the executive director is paid $220,000 annually. In Texas, the head of the 285-employee bar earns $315,986.

Tom Girardi and his firm were sued more than a hundred times between the 1980s and last year, with at least half of those cases asserting misconduct in his law practice. Yet, Girardi’s record with the State Bar of California remained pristine.

Davtyan, the new general counsel, previously worked at L.A. Care, a public healthcare plan. Duran said her $328,000 salary is reasonable compared with the demands of other candidates.

“It was less than some people came out of the gate asking,” he said.

Asked whether the salary was appropriate, Jamie Court, president of Consumer Watchdog, said, “It’s too early to tell.”

“I have no problem with her making a decent salary; the general counsel does a big job. But the incentives need to be aligned so that when the bar doesn’t do what it is supposed to do, then people don’t get raises,” he said.

Neither Wilson nor Davtyan is responsible for investigating and disciplining individual attorneys. That duty rests with the chief trial counsel, former federal prosecutor George Cardona, who was hired last year and reports directly to a committee of the governing board. He is paid $286,840, according to salary data posted on the bar’s website.

Robert Fellmeth, a former bar monitor who is consulting for the agency on reform of its disciplinary system, said he offered last year to work for free, but the bar insisted on paying him. He said he makes $50 an hour, which he donates to the University of San Diego’s Center for Public Interest Law, where he serves as executive director.

He said that without studying pay data, he could not weigh in on the executive salaries.

“I will tell you that levels that are that high absolutely warrant inquiry,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.