Heat waves are getting worse. When will L.A. get around to offering bus riders more shade?

- Share via

It was 103 degrees on a Friday afternoon as Ken Willis waited for the 152 Metro bus under a thick tree canopy in North Hollywood.

He didn’t even consider resting on the two bare metal bus benches baking in the sun. “If you sit on the benches, you just sweat to death,” he said. “On extremely hot days, the shade is not enough to keep you cool.”

With highs last week up to 110 degrees in the San Gabriel and San Fernando valleys, those who rely on buses to get around had no choice but to suffer the sun’s wrath.

Of the 12,200 bus stops served by the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority, only a quarter have some kind of shade or rain shelter, and only half have a seat for those waiting.

And waiting is what most bus riders do. While the average trip on a Metro bus is less than five miles, about half the time of that journey is spent looking down the road for signs of a bus.

Now with climate change threatening ever more heat waves and wetter storms in California, riders and transit advocates are demanding that officials do something to provide cover from the elements.

Metro is mapping all bus stops in the region to try to corral federal and state funds to add more shelters. And the city of Los Angeles, where the bulk of those riders are, is poised to approve a contract that would add thousands of its own shade structures. But similar efforts have faltered before. And even if these succeed, it still may be years before many get relief.

On hot days in the valleys, the nearby asphalt can approach 130 degrees, making conditions dangerous for those like Willis.

A new UCLA mapping tool alerts Los Angeles County residents of extreme-heat danger in their neighborhoods.

“People can have heatstrokes,” he said. “They need to get air-conditioned benches or some type of way of keeping the environment cool around here.”

The searing weather is yet another setback for largely low-income bus riders who often face long, difficult commutes. Willis has a car, but he’s been trying to save money with gas prices so high. Others don’t have options.

At a bus stop in East Los Angeles, sweat was trickling down the neck of 87-year-old Eva Griego on a recent morning. “There’s nothing I can do but wait,” Griego said as the sun rose and the shadows shrank.

Griego had left her apartment early to get to the bank, but it was already 83 degrees before 10 a.m. and the sun was burning her skin. A low-slung building nearby offered no shade.

“It’s hard but I don’t drive. I have to take it,” she said.

Scientists warn of more frequent and longer heat waves similar to the one in Southern California last week.

While more public transportation is a crucial step in California’s push to lessen climate change by reducing greenhouse gases, the system in Los Angeles County is largely one of last resort. The majority of riders are Latino and among the region’s poorest. The median household income for 62% of Metro riders is under $20,000.

Bus stops, the most frequent entry point to the public transportation system, are often tagged by graffiti, dirty and sun-beaten. Riders regularly search for a tree or sliver of shade next to a building.

The benches can be uninviting, many with bars in the middle designed to keep homeless people from sleeping there. Few are designed to reduce the heat.

Transit advocates say the agencies need to look to desert cities like Phoenix, where bus stop canopies equipped with misters and fans to cool riders have been installed.

“We actually have to make adjustments for the built environment — tree selection, street furniture and shade canopies, like they have in Phoenix in order to accommodate these days,” said Juan Matute, deputy director of the UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies. “Climate change is changing the base line of all these past decisions.”

The vast majority of Los Angeles’ transit users — half a million people on an average weekday this July — ride the bus. Roughly 150,000 jumped on a train during the same time. Despite billions of tax dollars going into county’s transportation system annually, advocates say that the state of bus stops is just part of the overall poor infrastructure, and that buses need to be faster, more reliable and easier to access.

“We are sick and tired of waiting for shelter,” said Eli Lipmen, executive director of the advocacy organization Move L.A. His group backed state legislation that would have required cities to create an inventory of bus shelters and streamline a difficult permitting process that has resulted in available federal funds for such structures going unused.

The lack of shade is an issue not just in Southern California but also across the state, where heat waves regularly strain the power grid.

In Bakersfield, where the temperature hit 115 last week, Golden Empire Transit District had about 16% of its bus stops shaded.

“We have a climate emergency right now,” Lipmen said. “We have too many people standing in the sun.”

For years, transportation planners at Metro didn’t keep track of their benches or shade. Agencies placed bus stops along determined routes that sometimes didn’t have sidewalks that could hold a bench. It has been largely up to cities where the agencies operate, like Los Angeles, to add benches or other amenities. That arrangement in many cities has led to a disconnect that left the neediest people without services.

Paved surfaces, tree cover, and home construction quality can make the difference between heat waves being an inconvenience or a threat to your life.

In Los Angeles, fewer than a quarter of its 8,000 bus stops have shelters. The city hopes to dramatically change that ratio. The City Council is poised to consider a 10-year deal with the startup Tranzito-Vector to install and maintain 3,000 new bus shelters in exchange for allowing the group to advertise.

The company, a joint venture between outdoor advertising company Vector and Bay Area micro-mobility operator Tranzito, says it will install real-time data on bus arrival, digital advertising and even some cooling features.

“The current system that we’ve had is badly broken. It has not worked,” Councilman Paul Krekorian said during a recent council committee meeting discussing the new contract.

Krekorian represents the San Fernando Valley, including Van Nuys, Sun Valley and North Hollywood, where researchers project the number of hot days will increase over the coming decades.

“If we ever have any hope of encouraging an expansion of ridership among those who are not necessarily transit dependent, we certainly will not be able to do so without investing in this kind of sheltering infrastructure and making it much more readily available across the city,” he said.

Unlike in previous agreements, the locations for bus shelters will be based on the area’s heat index, transit usage and economic needs. Planners hope that the new shelters will provide shade for at least 75% of bus riders.

Los Angeles has promised to pay for the $237 million in construction to build the bus shelters, but it hopes the program will pay for itself.

Under the agreement, which can be extended for up to 10 years, Tranzito-Vector projects it can generate $639 million in ad revenue over the lifetime of the structures, of which the city would get 60%.

Transit advocates object to the advertising-first approach, arguing that public funds should pay for a more appealing experience. And cities shouldn’t rely on placing bus shelters only where ad revenue can support it.

Gasoline prices have reached record highs in Los Angeles, but convincing tens of thousands of Angelenos to leave their gas guzzlers at home is still a hard sell for many.

“Why is the only way to get an improvement is if you can make money on it?” asked Jessica Meaney, executive director of Investing in Place, a transit advocacy group. “We are choosing a model that the only way you get a bus shelter is if it’s connected to advertising revenue. Bus stops and sidewalks are part of our transportation networks, and the city of Los Angeles doesn’t treat them that way.”

Much of the revenue is expected to come from 700 bus shelters where rotating digital ads will refresh every 10 seconds.

The effort to improve the stops has had a halting history.

Outfront JC Decaux, the last company the city contracted with to add bus shelters, installed about 660 of 2,185 promised shelters over their 20-year agreement, according to the city.

Ed Wallace, a lawyer for the company, said a complicated approval process stymied the program.

At one point it required 16 steps of approval and sign-offs from multiple departments and individual City Council members. He said the permits took so long to be issued that the company did not have time to pay off its investment.

Since then, the Bureau of Street Services has revamped the process so the city has more control over where the bus shelters go. City planners hope that 600 shelters will be added the first year of the contract, with that pace continuing for the next five years. But much of its success could depend on a turbulent advertising market. And ultimately, a council office could object to the shelters, as happened before.

Already, opposition is building among neighborhood groups that don’t want the digital billboards.

“These new digital bus shelters will put ads in most roads all over the city,” said Patrick Frank, the former president of Scenic Los Angeles, once known as the Coalition to Ban Billboard Blight. “No one has studied the safety of this.”

Digital advertisements for the latest movie or best attorney will distract drivers, he said.

“The sign is right next to the road. It faces the drivers and oncoming traffic, and it’s changing every 10 seconds. It’s meant to pull your eyes off the road. So yes, there’s definitely a safety issue,” Frank said.

He said the group is weighing a lawsuit demanding the city consider the effects on traffic and power usage.

“This is going to open the door toward other kinds of digital ads on the public right of way,” he said.

New city rules are being proposed to allow for these digital ads, which planners say will be no brighter than the backlighted paper of existing ads.

“The amount of light and distraction of the new shelters are going to be very minimal compared to our with our existing shelters,” Lance Oishi told a council committee last month. Oishi, who helps administer the program for the Bureau of Street Services, compared the illumination levels of the digital display to the brightness of candlelight.

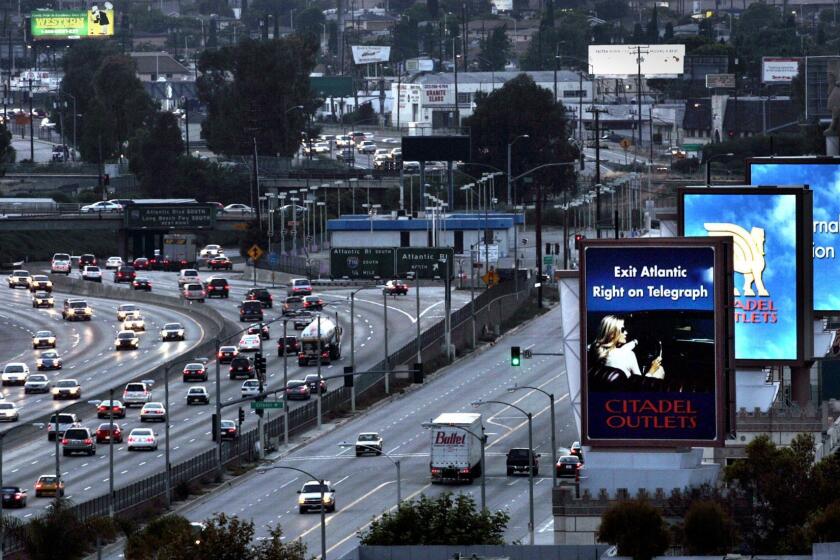

Once a rare sight, electronic billboards that flash new ads every few seconds have sprouted up by the hundreds along California freeways in recent years, much to the alarm of environmentalists and traffic-safety experts.

As the heat beat down last week, that was the last thing on Maria Salazar’s mind.

While other Angelenos retreated to their air-conditioned cars and homes, she sat under a tree in front of Pls Check Cashing in Boyle Heights, waiting for the 251 Metro bus to visit her sick father. It was nearing 90 degrees. About half a dozen others milled around, some standing under a scraggly tree along the mini-mart parking lot.

“I would like to see more shade at the bus stops,” she said.

She carried a yellow and white striped umbrella for the stops with no trees.

It was her second bus of the day, and despite the heat, she was in a sweater because inside the bus it can be frigid.

When told that new bus stops could be on the way with real-time information on bus arrival, she shrugged.

More than once, she said, she has waited for a bus that’s on time, only to be left behind when it’s full.

She eyed her approaching bus, waiting to get out of the heat.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.