Why L.A.’s ban on homeless encampments near schools, day care has become heated election issue

- Share via

Echo Park resident Stan Gale was seriously thinking of moving out of L.A.

The 66-year-old chiropractor used to hear screaming and gunfire in the middle of the night on Glendale Boulevard, where a homeless encampment occupied both sides of the street. Thieves broke into his car, ripped out his mailbox and stole packages from his front steps, he said.

Those problems largely disappeared, Gale said, after Councilmember Mitch O’Farrell designated the area as a no-encampment zone.

“I’m not Mr. ‘I love my politicians,’” Gale said, gesturing toward a landscaped area that is now fenced off. “But Mitch did this.”

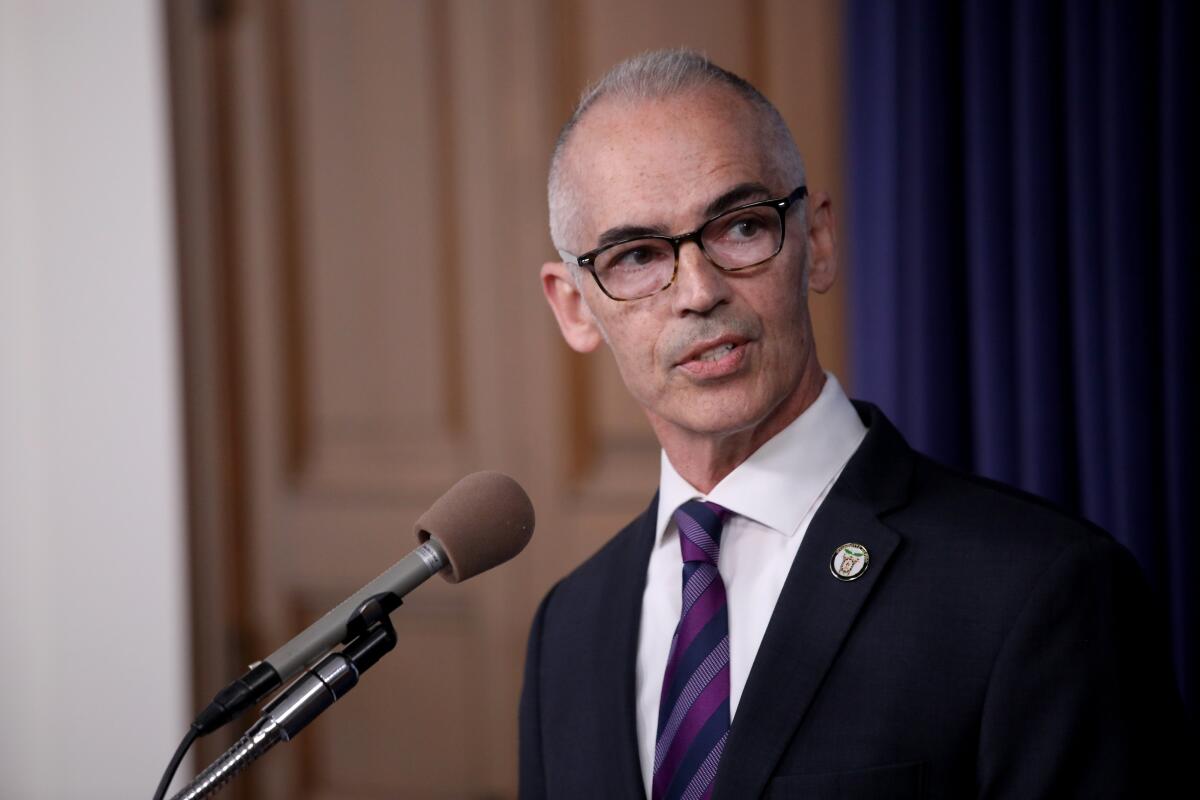

O’Farrell, first elected in 2013, has emerged as a proponent of the city’s controversial anti-encampment law, using it to designate 18 locations in Hollywood, Silver Lake and other neighborhoods as off limits to tents. But he is facing a vigorous reelection challenge from labor organizer Hugo Soto-Martinez, who has promised to take the district in a different direction.

Soto-Martinez described the anti-encampment law as ineffective, moving people around while accomplishing little. He told The Times he would work with neighborhoods to remove those zones and, if there is enough support on the council floor, repeal the ordinance altogether.

“If the votes are there, I think we should go for it,” he said.

Soto-Martinez is one of several candidates in the Nov. 8 city election taking aim at the anti-camping law, which allows council members to designate sidewalks at libraries, senior centers and other facilities as no-camping zones.

Porter Ranch lawyer Faisal Gill, running to replace City Atty. Mike Feuer, has promised not to prosecute people under the law, saying issuing citations for unpermitted camping is “not a viable solution.” Gill said he would advise the council that the ordinance is unconstitutional, and recommend they repeal portions of it.

Accountant Kenneth Mejia, running for city controller, appeared with dozens of protesters at City Hall two months ago at a chaotic meeting where the council expanded the law to cover more than 2,100 schools and day-care centers.

Mejia contends that the council has rendered about a fifth of the city off limits to L.A.’s unhoused population. He has vowed to audit the homeless programs of every council member — including the use of what he called “banishment zones.”

Meet the candidates: Civil rights lawyer Faisal Gill and finance law attorney Hydee Feldstein Soto

“We plan to use data to show that there is a better way to address homelessness instead of enforcing punitive laws like 41.18,” his campaign said in an email.

Few policy initiatives at City Hall have generated as much debate in recent years as L.A. Municipal Code section 41.18, which places numerous restrictions on where people can sit, sleep and store property.

Supporters say the ordinance is needed to protect children from dangerous conditions near their campuses and ensure that pedestrians and wheelchair users are not forced off sidewalks and onto busy streets.

Opponents call the law inhumane, saying it criminalizes poverty and can be scarring for L.A.’s unhoused residents, making them less receptive to offers of shelter and services. When homeless people are forced to relocate even a short distance, they can lose valuable property, such as their drivers’ licenses or other IDs, which are essential to obtaining aid, critics say.

“This idea of moving people from one side of the street to the other, causing more trauma and more distrust between government and [these] individuals, does not work,” Soto-Martinez said during a recent campaign Q&A. “We have to be leading with housing solutions.”

O’Farrell contends he is doing just that, opening “tiny home” villages, converting motels into low-cost apartments and financing permanent supportive housing projects — the kind that provides social services for unhoused residents. The anti-camping law, he said, is “certainly not the most essential” part of the city’s homelessness strategy.

“The essential part is getting people under a roof,” he added.

O’Farrell won approval last year of a 500-foot no-encampment zone around the Clifford Math and Technology Magnet, an elementary school run by the L.A. Unified School District not far from Gale’s home. Neighbors in the area, including school officials, repeatedly demanded that O’Farrell’s office address the trash and crime they said were associated with the Glendale Boulevard encampment.

Last summer, seven people near Clifford school were relocated to shelters or temporary housing, according to O’Farrell spokesman Dan Halden.

O’Farrell acknowledged that encampments remain in several of his 41.18 zones, saying outreach workers are moving strategically and with “compassion.” Meanwhile, homeless residents can be found on other stretches of Glendale Boulevard not far from Clifford school.

Echo Park resident David Montalvo, who lives out of a van about four blocks south of the school, said he knew many of the people living at the encampment. While some agreed to move into temporary housing, others, struggling with serious addiction, did not, he said.

Montalvo, 52, was not troubled by the creation of the zone around Clifford, saying nearby streets still offer “plenty of space.”

Still, the city’s law goes well beyond the no-camping zones. The ordinance bars tents from going up within two feet of fire hydrants, five feet of doorways and 10 feet of driveways. And it requires that sidewalks offer space for wheelchair users — at least 36 inches of clearance — in order to comply with the federal Americans With Disabilities Act, the landmark civil rights law.

Whether the council could assemble enough votes after the election to repeal 41.18, or seriously rewrite it, is difficult to discern.

Councilmember Nithya Raman, whose district is anchored by the Hollywood Hills, has been a longtime foe of the law. Councilmember-elect Eunisses Hernandez, a major critic of 41.18, takes office in December.

City Council candidate Danielle Sandoval, running to represent neighborhoods from San Pedro to Watts, said last week that the law should be “sent back to committee and amended.” Her campaign declined to explain how she would change it.

Katherine Tattersfield, who volunteers with the mutual aid group West Valley Homes Yes, is enthusiastic about the number of candidates who are speaking out against the ordinance.

“All 41.18 does is push people from one block to the next, and that doesn’t help anybody,” said the Chatsworth resident. “It doesn’t help people experiencing homelessness, and it doesn’t help people who feel unhoused people are blocking their streets.”

The fight over 41.18 has been especially pronounced in the race to replace Councilmember Mike Bonin, whose coastal district includes Venice and Westchester. Bonin, an opponent of the law, has declined to use the ordinance within his district and voted against the creation of new zones elsewhere.

Attorney Erin Darling, now running for the seat with Bonin’s backing, echoed many of the council member’s arguments, saying 41.18 simply results in a game of “whack-a-mole.” Last spring, while competing in an eight-way primary, he boasted that he was the only candidate to oppose the anti-encampment law.

In recent months, Darling has called the idea of repealing the ordinance a “far-off hypothetical,” telling The Times: “The law is the law.”

Darling’s opponent, attorney Traci Park, is taking a harder line, saying she would not only utilize 41.18, but expand it to cover hillside areas at risk of wildfire and sensitive ecological areas like Ballona Wetlands, home to a huge concentration of RVs.

“I’m going to seek to enforce it in every single area that is permissible under the ordinance — every school, every day care, every park and every library,” she said.

As the campaign has progressed, some of the candidates critical of 41.18. have also begun to echo neighborhood complaints. Darling told the outlet Circling the News that residents “should not have to endure open air-drug markets and obvious bike theft rings” at homeless encampments.

Soto-Martinez, speaking this month to the Windsor Square Assn. and other organizations, said city leaders may need to use “a little bit of tough love” to persuade people to accept offers of housing.

“We do not plan to enforce 41.18,” he told the groups. “It doesn’t mean we’re going to enable people to just be there and not move.”

Several other candidates have defended the law.

In L.A.’s harbor area, City Council candidate Tim McOsker said he supports the ordinance but would be open to changing it so it is carried out more consistently across the city.

Councilmember Paul Koretz, running for city controller, said he has no problem requiring that homeless residents relocate away from public schools. “If it’s a question of endangering our children, or asking folks in an encampment to move a couple hundred feet in a different direction, I think the choice is clear,” he said.

Attorney Hydee Feldstein Soto, running against Gill for city attorney, said she believes the ordinance can withstand a court challenge — if it is applied evenly throughout the city and accompanied by credible offers of shelter or housing.

“Just as we can put buffer zones around abortion clinics, we can put buffer zones around sensitive sites, like schools,” she said. “This is a public safety issue.”

Enforcement of 41.18 is also an issue in the race to replace Koretz, who is stepping down after 13 years representing the Westside. Attorney Sam Yebri has championed the law, saying it creates the urgency needed to “get people into shelters and into treatment.”

“It’s too easy for someone who’s unhoused to say no to shelter, or to treatment,” he said.

Yebri’s opponent, Katy Yaroslavsky, said she’s open to the idea of new anti-encampment zones, but only if the city provides housing and services in those areas. She also said she would not vote to repeal the law, even if there were seven votes to do so — one vote shy of a majority.

Yaroslavsky said the city needs to provide more housing, while also establishing “reasonable” rules around where encampments are allowed.

“You have a right to have a roof over your head. You don’t have a right to sleep wherever you want. That’s the difference,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.