- Share via

I was searching for my seat when a tall young man approached and shook my hand.

“Hello, I’m Jarvis,” he said in a firm voice.

For the record:

2:57 p.m. Nov. 15, 2022The headline and article say Father Gregory Boyle has spent 50 years as a Jesuit priest. He has been a Jesuit for 50 years, but a priest for 38 years.

Jarvis Thompson, 6-foot-5, wore a well-fitted burgundy suit and looked like a polished businessman. I assumed he was a supporter of Homeboy Industries, or maybe an executive there.

No, he said. He was in the program, meaning that he was in the two-year academy of former gang members trying to reclaim their lives after being locked up.

“I’m actually working in security now,” said Thompson, 28, whose problems began at an early age in South Los Angeles. He landed in juvenile detention and then jail, with an eventual release agreement that routed him to Homeboy over a year ago.

The occasion, Saturday night at Loyola High School, was the 50th anniversary of Father Gregory Boyle’s service as a Jesuit priest.

Los Angeles itself is a study in transition, leaders and trends come and go, promises are made and broken. Father Boyle, who attended Loyola High and later taught there, is a constant, present in the lives of the marginalized, carrying kinship and compassion to baptisms, weddings, funerals.

He is the patron saint of second chances and humility, and is purposeful always in saying you don’t go to the margins to influence others, you go to the margins to be influenced by them.

Time to retire? Absolutely, said some. Never, said others. After a year of research, I had my answer

I love work, but fear never having time for other things. Riding the boomer wave in search of the perfect sunset

Thompson sat next to my wife and me and said he was flattered to have been invited to the banquet. I asked if he’s been able to develop a relationship with Father Boyle while at Homeboy, where dozens of staffers teach, mentor, are help young men and women build confidence and map out new lives.

Absolutely, said Thompson, who pulled out his phone to show me a text exchange from earlier in the day.

“It means everything to me that you’ll be there tonight,” Boyle had written.

“I will be there pops! I’m excited and proud of you,” Thompson had responded.

He told me he’s a changed young man since joining the Homeboy family.

“I’m feeling better, I’m looking better, I’m acting better,” Thompson said. “I’m who I should have been all along.”

Throughout the evening, video tributes filled giant screens. President Biden and the first lady weighed in, as did Gov. Gavin Newsom and a host of others. Labor movement icon Dolores Huerta took to the stage to hail Boyle’s community-building work as a response and antidote to racism, poverty and inequality, and led the crowd in a chant of “Viva.”

If Boyle was at all uncomfortable with so much high praise for doing what he thinks of as both a duty and an honor, he dealt with it by busying himself, visiting each table to say hello and thank people for supporting the Homeboy cause.

What’s extraordinary is the number of lives resurrected on the power of love and compassion. The work of Boyle and his committed brothers and sisters has woven a new set of narratives into the story of Los Angeles, with hope trumping despair.

“We have a master here and I have much more to learn.”

— Hector Verdugo, who went to Homeboy in 2006 after a stretch in prison and is now associate executive director.

Also seated at my table, across from Thompson, was Hector Verdugo, who went to Homeboy in 2006 after a stretch in prison and is now associate executive director. Verdugo’s father died of a drug overdose before he was born, and like so many others, he came to think of Father Greg as his dad.

“I went to talk to him and vented a little bit,” said Verdugo, who recalled asking if Boyle could help him find a job. “He was like, ‘Son, I want you to work here,’ and he said, ‘God wants you to work here,’” said Verdugo. “For me ... I felt, like, ‘Ding!’ That’s what I needed to hear — God wants you to work here. I had been praying to God, ‘What do I need to do?’ I had dropped out in eighth grade. I was good at street things, but not in other ways.”

Boyle shepherds desire and effort from his troops. Some of them struggle with hard rules and lofty expectations, as well as with the enduring damage of trauma, heartbreak, and the powerful lure of old habits. His love is tough, but unconditional, which is something Verdugo admires but can’t always match.

“We have a master here,” he said, “and I have much more to learn.”

Also seated at our table was Ruben Rodriguez, who was raised with seven brothers, by their mother, in the projects near Dolores Mission, where Boyle worked in the days before Homeboy.

I’d first spoken to Rodriguez last year, when he told me his late mother had been a soldier in Boyle’s quest to keep kids out of gangs and form truces among those who were already snatched away. In those days, Boyle could be seen on a bike, racing in the direction of gunfire.

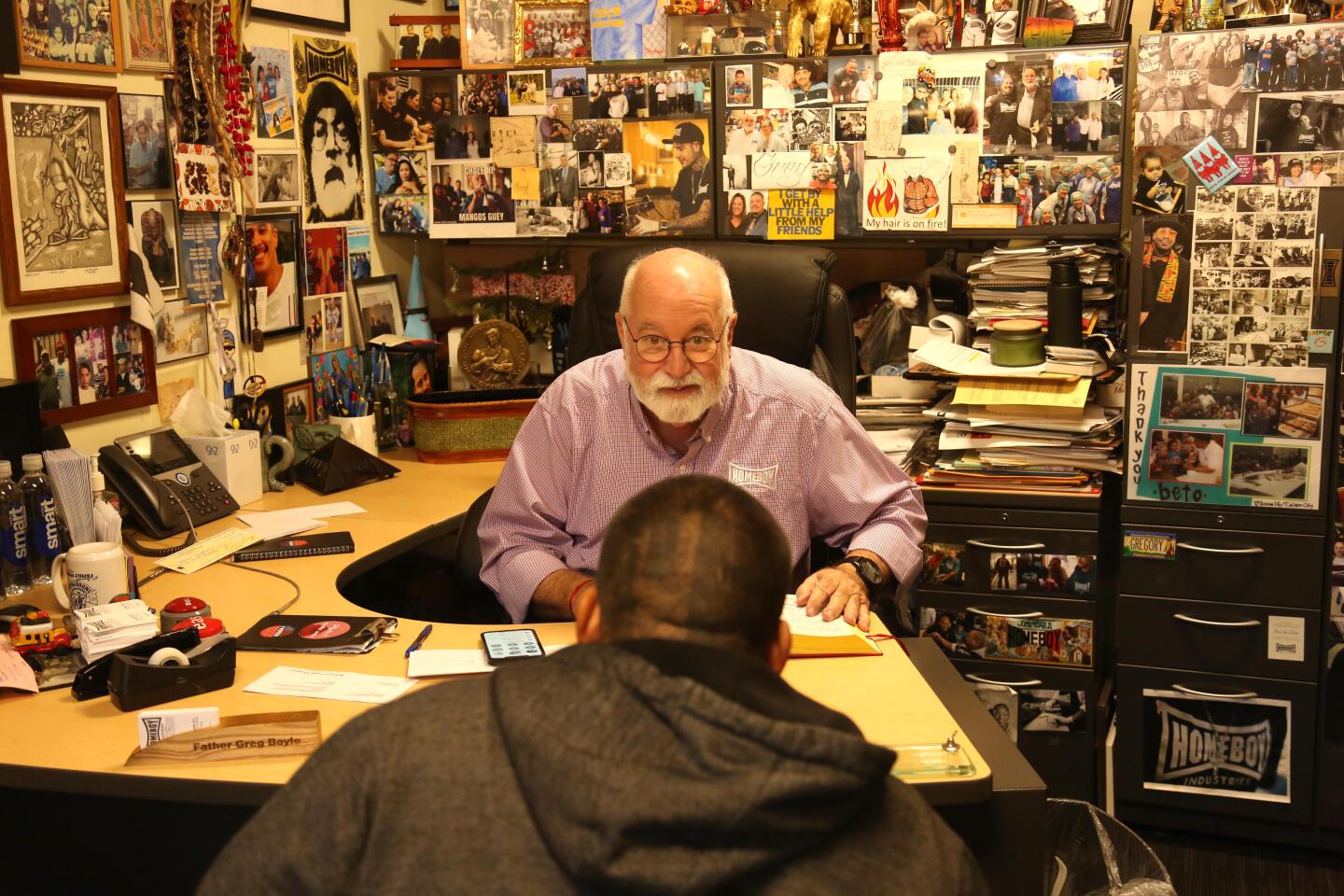

I dropped by Homeboy Industries to check in with Father Greg Boyle and to go over the details of our appearance together at the L.A.

At a low point in his own life, Rodriguez said, “I felt like things were spiraling out of control,” and people told him he was following in the footsteps of his absentee father. “One day Father Greg tells me, ‘You know what, I need some help at the bakery.’”

That kept him busy until Rodriguez and his wife, Cristina, began the Homeboy silk screening business that has employed hundreds of young men and women.

Throughout the banquet hall, this was how it worked. Those whose lives were transformed by Homeboy were seated with those in a position to support the cause. Another case of Boyle sharing stories, making introductions, building bridges. And then came the video reel of homie tributes, some of them tearful.

“He’s just my inspiration, like my dad that I never had.”

“For everything you’ve done, I love you.”

“He gave me a hug, and it was like, electrified. I was in a safe place.”

“Father Greg is an angel.”

“He returned me to God because I had so much shame and guilt over everything that I had done.”

“He’s made me feel like I matter.”

Up to the stage stepped the man of the hour — of the last half century.

Boyle said it’s been his privilege to “stand in awe at what folks have to carry rather than in judgment at how they carry it.” He called the homies who paid him tribute “anthems of resilience who have come to know the truth of who they are.”

They are us, he said, and the distance narrows in recognizing we “all are born into this world wanting the same things.”

“We are all invited into this exquisite mutuality where there is no us and them,” Boyle said. “Once we know that we are unshakably good and that we belong to each other, we can roll up our sleeves … and create anew this place of love and belonging that God would recognize.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.