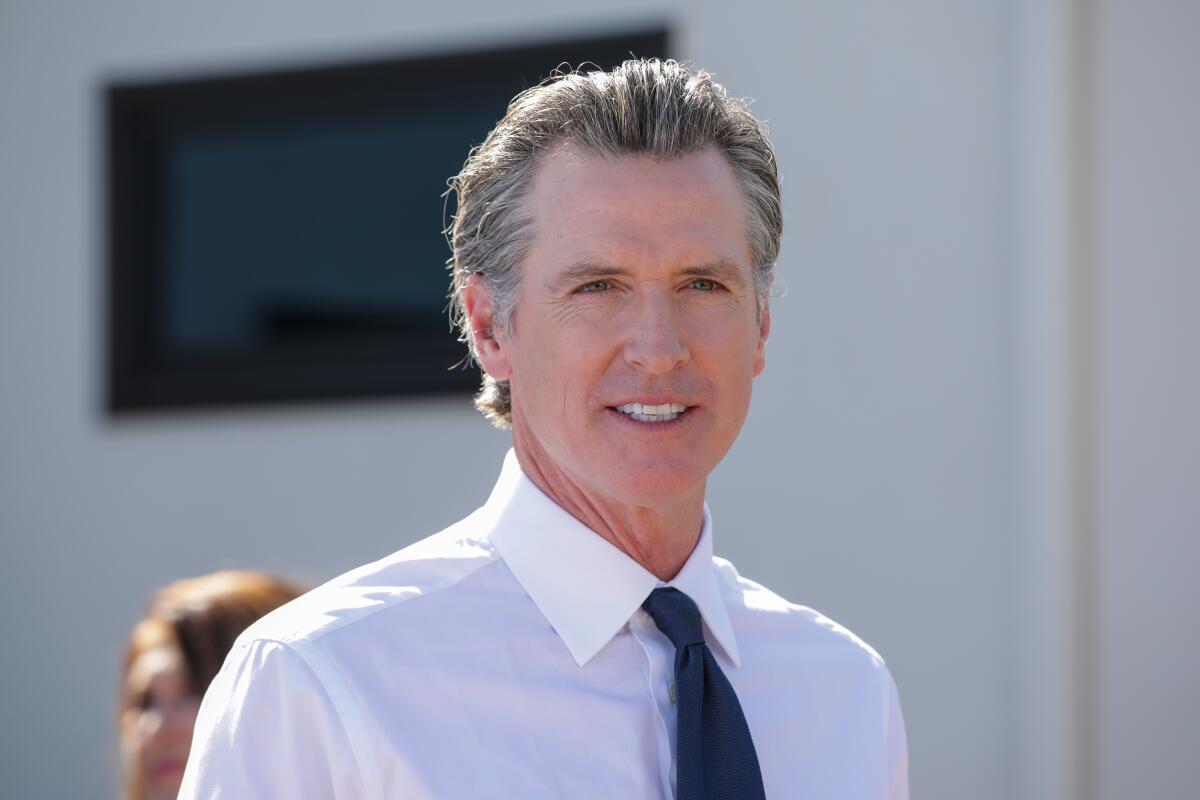

Newsom slams Republicans for blocking immigration reform on visit to Mexican border

- Share via

IMPERIAL COUNTY — While visiting a state-funded migrant center that provides services to asylum seekers near the Imperial County border with Mexico on Monday, Gov. Gavin Newsom criticized Republicans in Congress for politicizing immigration while failing to support comprehensive reforms.

Due to the lack of federal support, the governor said the state has spent nearly $1 billion working with nonprofits to provide immigrants released from federal detention with health screenings, temporary shelter and help connecting with sponsors over the last three years at nine facilities in Imperial, San Diego and Riverside counties.

“With the respect to the federal government, we’ve been doing their job for the last few years at scale,” Newsom said. “But we cannot continue to absorb that responsibility.”

The governor visited the center before he finalizes his budget proposal for the upcoming fiscal year. The state faces financial pressure of an anticipated budget deficit and, at the same time, a potentially greater need for immigrant support services under changes to federal policy for asylum seekers, he said.

“Everyone needs to get off their ideological perch and start dealing with the reality in a comprehensive manner,” Newsom said. He criticized the GOP and conservative news pundits for exploiting immigration as strictly a border security issue and ignoring the need for sweeping reform.

In November, a federal judge struck down a controversial border policy known as Title 42, a public health law used by the Trump administration during the COVID-19 pandemic to allow border agents to expel migrants.

Newsom, who crossed the border earlier in the day to visit a Mexicali shelter, made the trip as he continues his push into the national conversation on issues at the center of America’s culture wars, elevating his profile as a preeminent Democratic voice and heightening speculation about his political aspirations.

Dan Schnur, who teaches political communication at USC and UC Berkeley, said all governors with a significant immigrant population should have a voice in the debate. In California, immigrants make up one-third of the labor force.

Governors with an eye on the White House may have an added incentive, he said.

“This is another example of how Newsom can both support Biden for reelection, but also set himself up for a national role further down the line,” Schnur said.

Newsom applauded President Biden for introducing an immigration reform package early on in his presidency and centered his criticism on Congress for not appropriating more money to support migrants.

The state began funding services in 2019 for immigrants arriving in California after the Trump administration ended a program that sought to connect asylum seekers with family members in the United States, the governor’s office said.

“It was based upon conversations I had on the campaign trail with people saying, ‘We’re dropping kids off at the Greyhound bus station alone at night, and they’re sleeping on the street,’” Newsom said, adding that the lack of government support also left children and families vulnerable to human trafficking.

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, the state expanded its efforts in 2021 and began working with nonprofit organizations to fund facilities that provide immigrants with health screenings; COVID-19 and flu vaccinations; and basic supports, such as clothing and toothbrushes. The governor’s office said the three counties have served over 200,000 migrants and provided 36,316 vaccinations.

Some of the facilities provide temporary housing and nonprofits work with immigrants to help them set up travel connections to more permanent destinations, or relocate them to local shelters.

Workers at the center on Monday said ICE buses migrants to ports of entry, and the state and nonprofits then transport them to the facilities. Immigrants took seats in a large room, where they received health screenings and talked with staff about other pressing needs.

Pedro Rios, the director of the U.S.-Mexico border program at the American Friends Service Committee, a Quaker organization that advocates for immigrants, said that the funding from the state had helped support a “small, but robust” shelter network in San Diego County.

The shelter system has helped families transition “from a state of vulnerability to having greater security.”

“Through these efforts, many migrant families have received the medical care and legal support they wouldn’t otherwise have access to,” he said in an email.

Kate Clark, senior director of immigration services at the Jewish Family Service of San Diego, said she believes that California, along with other border states, will see an increase in the number of immigrants arriving in the region after the lifting of Title 42.

The organization operates shelters for migrants in San Diego County and has received funding from the state for the work.

“The state has really been an incredible partner in this work,” she said.

The Newsom administration said need for those services could increase.

Under Title 42, the Trump administration was able to use the pandemic as a reason to reject migrants at the border without offering them the opportunity to request asylum or other humanitarian protections. Biden announced plans to lift the public health order in April and faced legal challenges from Republican states that argued it would create chaos.

A federal court sided with the American Civil Liberties Union in a challenge of the law, which will pave the way for immigrants to once again cite fear of being returned to their home countries in order to gain access to asylum protections in the U.S.

In California, the extent to which Newsom intends to fund support services for asylum seekers and other immigrants is an open question as the state anticipates a $24-billion budget deficit in the next fiscal year. The governor in January is expected to released his spending plan for the upcoming budget year.

Though the Newsom administration in May forecast a $97-billion surplus by summer, the Federal Reserve’s efforts to raise interest rates to slow inflation led the Legislative Analyst’s Office to predict the weakest economic performance “the state has experienced since the Great Recession.” Revenues are expected to come in $41 billion below projections during the current fiscal year and into the summer of 2024.

Knowing that California’s fiscal heyday would eventually end, Newsom and lawmakers restricted much of the money in the current budget for new programs to one-time funding. The LAO said the state should be able to cover nearly all of the shortfall with its general-purpose budgetary reserves.

But budget analysts warned that the deficit could grow if the U.S. economy plunged into a full-blown recession and have advised lawmakers to seek to pause, delay and reassess certain budget priorities. The governor and state lawmakers already have approved plans to expand Medi-Cal eligibility to all immigrants in 2024, which Newsom doubled down on Monday.

“I’m committed to it,” he said.

Newsom’s appearance at the border makes him among the most high-profile Democrats to recently make the journey during a time when Republicans seized on immigration as a political issue and cudgel to hammer the Biden administration and Democratic leaders.

Biden visited Arizona last week and faced criticism from Republicans for not stopping at the border, which he has not done since taking office in 2021. The president went to Arizona to visit a Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. plant in Phoenix as the company announced plans to expand to a second facility and invest more than $40 billion in the state.

Newsom traveled to El Salvador in 2019 to better understand the forces driving immigration to the United States. His embrace of the Central American country stood in contrast to then-President Trump’s efforts to rescind deportation protections for Salvadorans and threats to cut off foreign aid.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.