An L.A. school trainer was investigated for sex abuse. Accusers want to know how he kept working

- Share via

When she entered the athletic training room six weeks into the school year, a Birmingham Community Charter High School cheerleader assumed the treatment for her sprained ankle would be the same as always.

But instead of the usual icing, stretching and taping, the 17-year-old said a trainer whom students called “RT” began massaging her leg with oils. He started at her calf, then moved up to her thigh, she said.

The girl, whom The Times is not identifying because she has alleged a sex crime, said she was lying on a table in a busy training room with other students at the Lake Balboa school. She was wearing a hoodie and shorts with a towel draped over her midsection.

“He went through my thigh and underneath the towel. He went under my underwear, moved it and began touching me inappropriately,” she told The Times. When she told him she needed to leave, he asked, “Was everything OK?”

Hours later, she broke down at home and told her parents. They immediately went to the Los Angeles Police Department’s Van Nuys station to report the incident.

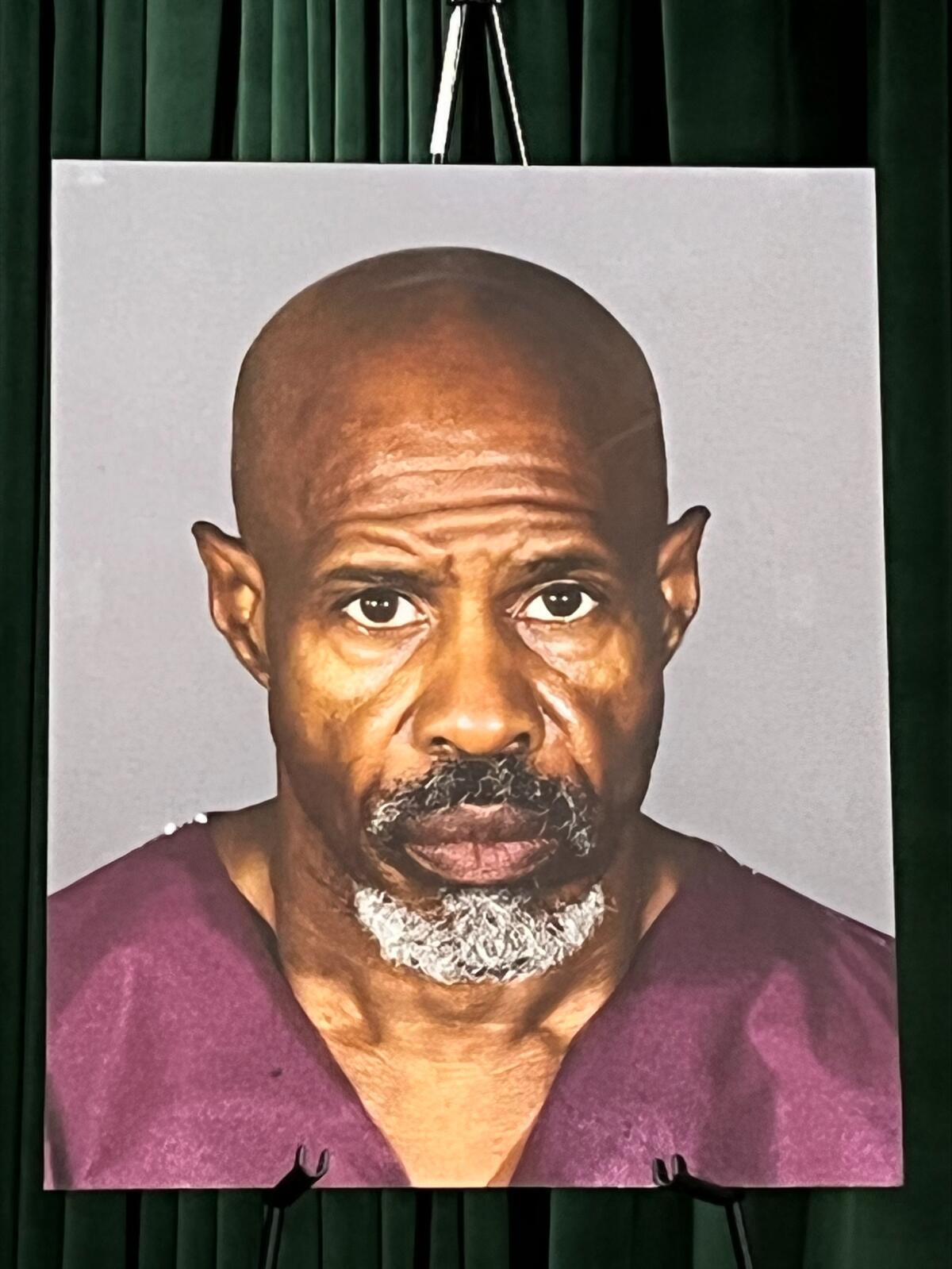

On Sept. 21, Richard Alexander Turner, 64, was arrested on suspicion of forcible penetration.

Turner’s name was familiar to police. In 2017, a female student at Van Nuys High reported to the school that she had been touched inappropriately by Turner, who was working as an independent contractor at the time. Although a police report was filed, according to officials with the Los Angeles Unified School District, the LAPD cited a lack of evidence, and no arrest or charges followed the investigation. Turner’s contract “was immediately terminated,” the district told The Times.

After the Birmingham allegation, police immediately linked the two reports — and found other girls who alleged abuse at the hands of Turner.

Richard Alexander Turner, 64, has been charged with multiple counts of sexual assault against young women he treated while working as an athletic trainer in Los Angeles high schools.

He since has been charged with the sexual assault of nine girls at Birmingham High as well as the Van Nuys High incident.

The alleged abuses, which involved female students ages 15 to 17, not only became more frequent over time, but also more violent, prosecutors said in a bail motion. Turner is accused of molesting another female student the same day the cheerleader reported her assault.

He faces 18 counts of rape, sexual battery, sexual assault of an unconscious person and forcible oral copulation. Although the alleged encounters included in the charges against Turner spanned from 2017 through 2022, all but four are alleged to have occurred between May and September of this year.

Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón said in a news release after Turner was charged that some of the incidents happened on campus during treatments for sports injuries, while others occurred outside of school. Prosecutors allege that some happened in Turner’s Chevy Suburban, which they say contained a mattress. In one instance, he is accused of using a trip to a sporting event to rape and forcibly orally copulate a student-athlete.

An attorney listed for Turner did not return calls for comment.

The Birmingham cheerleader wonders how Turner was allowed to continue working with young girls after a previous assault allegation was made against him.

“What happened to checking someone’s past and everything?” she said, noting in an interview that she is speaking out in an effort to change the hiring process in a case that raises questions about how background checks are conducted for school athletic trainers, who work directly with students in exercise and physical therapy.

Attorney David Ring, who represents the teen, said it is “inconceivable” that Turner was under criminal investigation in 2017 at Van Nuys High and was later hired at Birmingham, “where he is allowed to massage and touch student-athletes under the guise of providing sports treatments.”

Terry Gillard is serving 71 years for dozens of felonies. His child victims sued, alleging that L.A. Unified did not remove him.

Neither L.A. Unified nor Birmingham High, which is no longer part of the district, would provide complete information to The Times on Turner’s hiring, so some of the circumstances are unclear. But both the district and Birmingham have previously had problems with workers who have been accused of sexual misconduct.

L.A. Unified said Turner began working for the school system as an independent contractor on July 15, 2017. The district would not confirm whether he worked at Van Nuys High as an athletic trainer, but it did not dispute police and prosecutors’ accounts on that point.

“Turner had no previous criminal record or reports of misconduct” before his hiring, L.A. Unified officials said in a statement.

Six weeks after he started, a female Van Nuys student alleged “misconduct,” and “the school administration immediately contacted law enforcement and filed a suspected child abuse report,” the district said. Turner’s contract “was immediately terminated” on Aug. 31, 2017.

Los Angeles police tell things a little differently, saying detectives alerted the school system of the misconduct allegation — not the other way around. But both entities agree that no charges were filed.

After the accusation, “he never again contracted or worked for the district,” L.A. Unified officials said in a statement. The district’s position is that it acted legally and appropriately by immediately reporting the allegation to police and by canceling Turner’s contract. L.A. Unified officials did not comment on whether the district believed the allegation to be true.

Unlike with teachers, there is no umbrella agency in California overseeing the licensing of athletic trainers to which the school system could report concerns.

LAUSD officials did not respond to questions related to district policy on how unproven accusations of sexual abuse are recorded, if at all, on internal records related to contractors. It is unclear whether the lack of charges in the Van Nuys accusation may have protected Turner from any official disclosures on his employment record that could have prevented him from being hired elsewhere.

Ky E. Kugler, president of the California Athletic Trainers’ Assn., said California is the only state in the nation that doesn’t license athletic trainers.

Two years after the Van Nuys accusation, in September 2019, Turner began working at Birmingham High, which since 2009 has been an independent charter school. Such schools — there are 224 in Los Angeles — function like mini-school districts, each with its own board of directors. The school district is Birmingham’s landlord and periodically must renew its independence.

But the district and the school have no access to each other’s records.

A former student at the Thacher School is suing the prestigious Ojai boarding school, alleging she was repeatedly sexually abused by a counselor and soccer coach.

In response to The Times’ questions, Birmingham Athletic Director Rick Prizant issued a statement saying Turner’s fingerprints had been run through the California Department of Justice before he was hired.

“Mr. Turner was live scanned, and there was no mention of him working at Van Nuys High or any school in LAUSD on his application. His scan was negative,” said Prizant, who has overseen athletics at Birmingham since 1998.

According to Turner’s contract, his business — Active Healthy Living Life — was retained yearly and paid $4,500 a month.

The school, however, refused to disclose to The Times any emails or internal communications about Turner’s conduct and whether there had been any complaints before his September arrest. Ari Bennett, Birmingham’s principal, said he couldn’t comment because of pending litigation.

This is not the first time the school has dealt with a sexual misconduct case.

Turner was hired a few months after the conviction of Scott Silva, a Birmingham science teacher and lacrosse coach sentenced to nearly 11 years in prison for multiple counts of child molestation, sexual battery, false imprisonment and lewd conduct on a child. Eighteen girls — all student-athletes — reported being molested or touched inappropriately by Silva between 2016 and 2018, when the LAPD arrested him.

As a coach, Silva worked under the supervision of Prizant, Birmingham’s athletic director, who also hired Turner. Prizant said he had no knowledge of any allegations against Turner prior to his arrest.

In a lawsuit filed against Birmingham and two other schools where Silva had worked, attorneys alleged that Birmingham’s administration neglected to conduct a thorough background check of Silva that would have turned up misconduct allegations at the other schools and missed warning signs that could have prevented or limited the abuse when he was hired in August 2009.

Patricia Lynch, an attorney who represents Birmingham, said in an email that she couldn’t address any allegations against the school because there is still outstanding litigation, but she acknowledged the original suit was settled for $18 million, with no acknowledgment of wrongdoing on Birmingham’s part. She would not disclose from where the money was disbursed.

New allegations of sexual abuse surfaced in court against Servite High School’s Father Kevin Fitzpatrick, bringing the total of alleged victims to eight.

Last month, Garo Mardirossian, an attorney who represented plaintiffs in the Silva lawsuit, filed a new suit on behalf of one of Turner’s accusers, alleging a history of indifference in the Birmingham athletic department to sex abuse allegations and citing evidence from Silva’s criminal investigation. The lawyer’s teenage client is one of three suing the school.

Like Prizant, Bennett also was involved in hiring someone who later was convicted of abusing students.

Wrestling coach Terry Gillard is serving 71 years in prison for sexual abuse at a local Boys & Girls Club and at John H. Francis Polytechnic High in Sun Valley, where Bennett was principal at the time. In October, L.A. Unified paid $52 million in a settlement to a lawsuit that alleged the district knew of Gillard’s prior sexual misconduct and did nothing about it.

The district has paid out more than $250 million in judgments, settlements and legal costs in sexual abuse litigation over several decades. It did not comment on the Gillard settlement, which, as in the Silva case, did not include any acknowledgment of wrongdoing.

Bennett allowed Gillard to return to Poly in 2016 after he was accused of sexual harassment and soliciting an employee for sex for money. At the time, there were no allegations involving students.

Bennett told The Times in an email that he allowed Gillard to return after evidence in an investigation by L.A. Unified — which touts a zero-tolerance policy for abuse — proved inconclusive, and investigators said it was up to him whether to bring back the popular coach. He said he took the input from investigators as reassurance that students would not be endangered.

“There was a 6-month investigation by the best investigators in the district,” Bennett said. “Presumably, they conducted a thorough investigation, speaking to students and parents in addition to Gillard and the complainant. How in the world could I think it wasn’t safe to bring him back when they gave me the choice to bring him back? If they thought he was a danger to students or staff, would they have put that choice in my hands?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.