Column: McCarthy’s Mar-a-Lago trip was his tipping point. It showed he could be bullied into submission

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — House Speaker Kevin McCarthy weakened himself two years ago by calling out then-President Trump for inciting the violent Capitol insurrection, then rushing to his golf resort to beg forgiveness.

That was the tipping point for the Bakersfield Republican. It showed everyone — including future far-right opponents of his speakership — that he could be bullied into backing down. He had no hard and fast convictions. His words couldn’t be trusted. He lost respect among allies and enemies alike.

That’s how I figure it, anyway. And he disappointed some politicians, consultants and lobbyists who remember him as a trustworthy, straight-shooting Republican legislative leader in Sacramento.

McCarthy has spent six years kissing Donald Trump’s ring in an effort — now proved successful — to elect enough Republican House members to crown him speaker.

But in appeasing Trump and the far right, McCarthy lost credibility. That led to last week’s Republican debacle when four days and 15 ballots were required before the Californian could be elected speaker. Meanwhile, he was shoved around by “Never Kevin” hard-liners demanding and receiving concessions.

OK, hold on. That may be accurate, but it’s also simplistic. It’s not the whole story. The underlying truth is that the politics McCarthy grew up with and mastered in California is no longer as effective in polarized America as it was pre-Trump, pre-social media and pre-Fox News.

McCarthy climbed the political ladder from volunteer gofer for a hometown congressman to U.S. House leadership by building relationships and compromising.

But for many of today’s demagogic politicians, relationships — even with leaders — aren’t as important as social media clicks and cable TV interviews that enable them to communicate directly with a monolithic, anti-Washington political base. They’re cheered for attacking a potential House speaker, not collaborating with him.

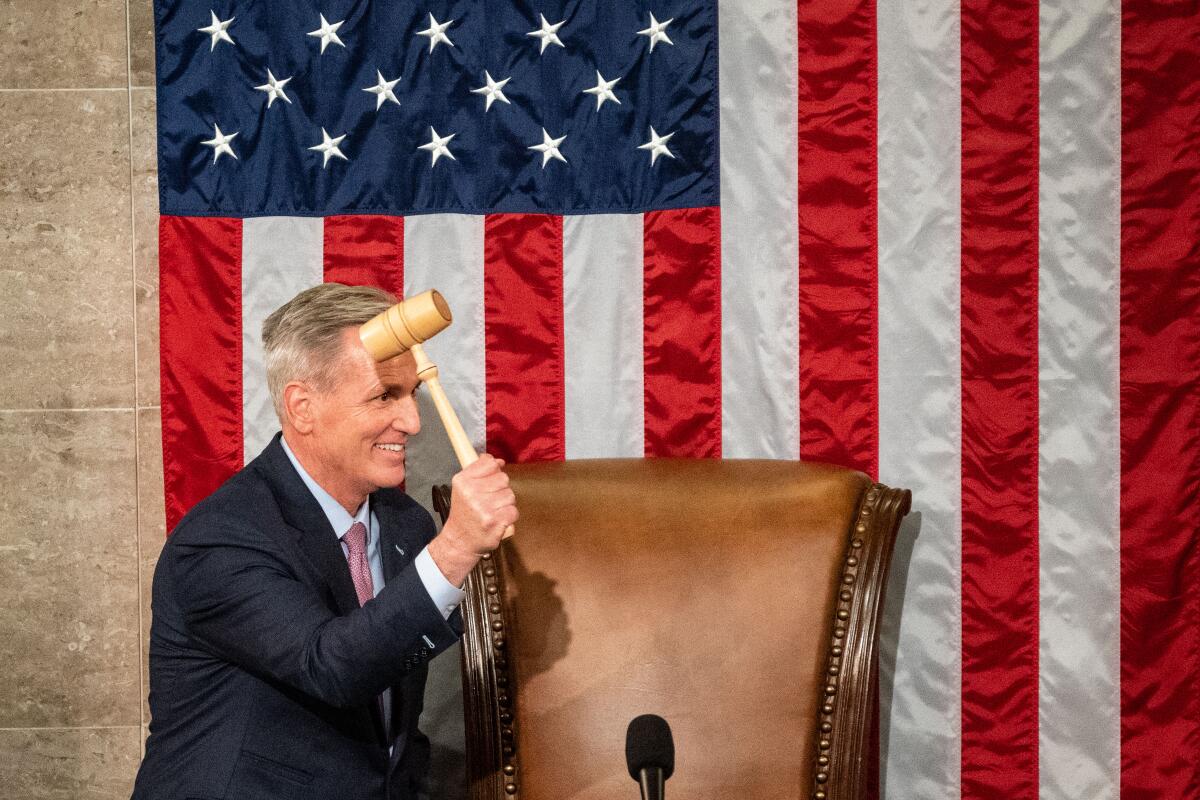

Kevin McCarthy’s decades-long dream of becoming speaker of the House was nearly brought down by a band of Republican radicals.

In this climate, the two-party system — an essential ingredient of American democracy — is disrespected.

When it’s working effectively, party caucus members fight among themselves, then reach consensus on a leader and publicly unite behind the winner. McCarthy was backed by 91% of House Republicans, but 9% rebelled and stubbornly blocked his ascension for four days. That hadn’t happened in a century.

“Politics is a team sport,” says former state Sen. Dick Ackerman of Irvine, who was the Senate Republican leader when McCarthy led the Assembly GOP from 2004 to 2006.

“It’s like 11 football players line up and two guys decide they’re not going to run the play that was called. How’s that going to work? It’s not.”

In this era’s polarized politics, compromise has become a dirty word among extremists on both the right and the left.

“For most of the 20th century, being a deal maker in Congress was considered to be a good thing. But during the speakership fight, ‘deal maker’ was an insult used against McCarthy,” notes Dan Schnur, a political science professor at USC and UC Berkeley and a former Republican operative in Sacramento.

“The same skill that allowed Kevin to succeed in Sacramento has become his biggest obstacle in Congress.”

Well, yes and no. It’s ironic. House rebels accused him of compromising on principles — although the consensus among pundits is that he doesn’t have any principles. Yet the rebels demanded he compromise on rules changes before they’d allow his election.

The national drumbeat is that McCarthy coveted the speakership so much that he surrendered much of its power to acquire the office.

The Republican leader’s victory came at a price: McCarthy had to agree to a series of compromises that dramatically weaken the power of his new post.

“At some point you’ve just got to say ‘no,’ ” Ackerman says.

Republican consultant Mike Madrid, who was political director for the state GOP when McCarthy ran the district office for former Republican Rep. Bill Thomas of Bakersfield, says:

“This is the story of someone who has spent his entire career climbing the ladder by placating the right wing and has almost been consumed by it. If you feed the alligators, when you have nothing else to feed them, they’re going to eat you.”

But the rap on McCarthy for giving away too much could be off base. We don’t know yet how these rules will work. They may turn out to be relatively innocuous. In legislative bodies, there are always paths around rules if there’s strong-willed leadership.

The new speaker has been ridiculed for allowing far-right Freedom Caucus members more seats on the powerful Rules Committee. But coalition governing is normal in most democracies. What’s different here, of course, is that the coalition is solely within the GOP. Democrats are barred.

McCarthy is remembered in Sacramento as a pragmatic centrist, personable and down-to-earth.

When he was Assembly minority leader, Republicans still were relevant in the state Capitol. Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger was governor. Democrats held a comfortable Assembly majority, 48 to 32, but it wasn’t a supermajority like today’s 62 to18. Unlike today, state budgets required a two-thirds vote, so the GOP was in play.

Back then, I wrote that McCarthy was “mainly a deal maker rather than an ideologue. A pragmatist, not a policy purist. A political junkie.” Little has changed.

“He was very easy to work with, a straight shooter — not someone who would say one thing and do another,” recalls then-Assembly Speaker Fabian Núñez, a Los Angeles Democrat. “He was very likable. And incredibly competitive.”

GOP consultant Rob Stutzman, who was Schwarzenegger’s communications director, recalls that McCarthy “would stand up to Arnold when it was needed for the Republican caucus.”

Except for one fleeting moment, however, he apparently has never stood up to Trump.

Last week, Trump tried to help McCarthy by urging hard-liners to stop blocking “my Kevin.”

So, it’s a mixed bag. Crawling down to Mar-a-Lago two years ago made McCarthy look weak. But if he hadn’t, would the Bakersfield native have become speaker? We’ll never know. But he’d be more respected.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.