LAUSD pitched students an expensive experiment to get higher grades. Most turned it down

- Share via

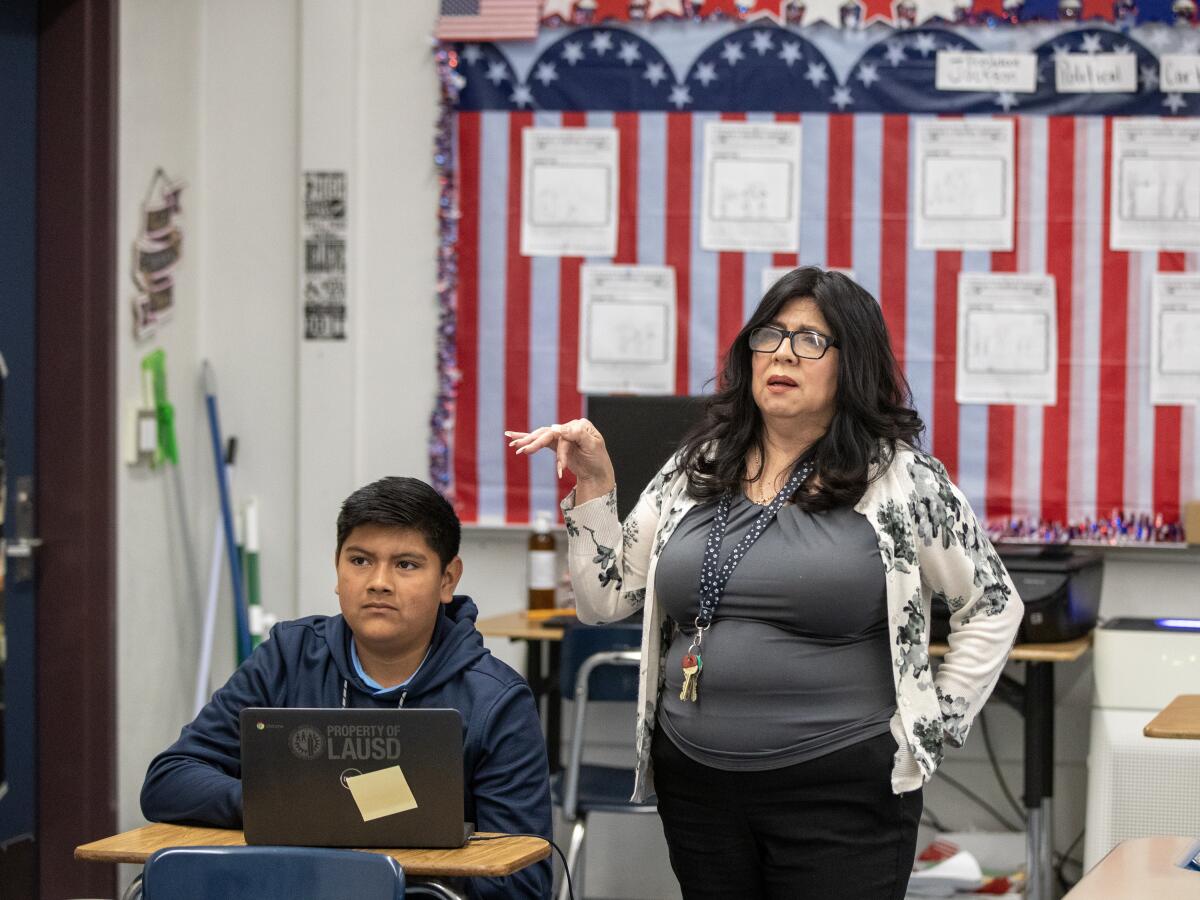

Despite failing every class — or because of it — Rebbeca Avelino, a 14-year-old eighth grader, wanted time off from school during spring break. But history teacher Lorraine Escalante pressed her to attend two “acceleration days” in the Los Angeles Unified School District.

“She knew that I was doing bad,” Rebbeca said. “And she wanted to encourage me and she’s like: ‘You could do it. Don’t let anybody stop you. You can do it. You can reach those goals if you try, and you should come.’”

Rebbeca became part of an expensive, massive and controversial experiment in the nation’s second-largest school system — a key initiative, made possible by COVID-relief money, to fill gaps in student learning exacerbated by the pandemic. The money has to be spent by September 2024.

Low participation ultimately limited the impact of the four “acceleration days” — two over winter break and two over spring break — as families opted for vacation time over class time. The relatively high-cost project had been envisioned as way of reaching all students— especially the 58% below grade level in English Language Arts and 72% below grade level in math. Last week’s spring break installment pulled in fewer than 8% or 33,076 of the district’s 422,276 students for one or both days. During winter break, 36,486 students attended one or both days.

Imperfect planning and inexperience with the format also were impediments, although administrators tried to learn from the December experience. One example is that they focused harder in the spring on recruiting the students most in need.

Some students who attended received individualized help; others did not. Many talked of fun activities, practicing basic skills, prepping for Advanced Placement tests or pulling up grades. Some teachers and students described a unique, calming and rewarding learning environment for those who did take part.

The cost of the days is difficult to discern because the district has declined to release detailed information that The Times first requested three months ago.

In a January presentation at a school board meeting — a month after the first acceleration days — officials said those two days cost $36 million. After public backlash over the costs, L.A. schools Supt. Alberto Carvalho announced that the actual cost was $11.6 million. The district, however, has declined to provide backup documentation to support the changed figures.

The costs at the participating 354 campuses included teaching and support staff, food services and student transportation.

From the start, the acceleration days were a compromise, the surviving element of a failed try for a longer school year, which did not have widespread parent support and was opposed by the teachers union. Originally the optional days were scheduled for Wednesdays as an incentive for workers — who would be paid extra — and students to continue their weekday routine. The school year would have ended four days later. Officials hoped for almost universal participation.

But the teachers union filed a labor board complaint — contending that the four optional days had to be a subject of negotiation. The district backed down, moving the days into winter and spring break.

The results of extended learning “can hinge on whether the extra learning time is mandatory or voluntary for students,” said Dan Goldhaber, who directs the Center for Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Education Research at American Institutes for Research. “The most common form of extra time is summer school, and the research on summer school pretty clearly shows that a big problem is low attendance.”

Many of the most effective tutoring efforts are provided during the regular school day, in coordination with a child’s teacher, said Professor Susanna Loeb of Stanford’s Graduate School of Education, an authority on tutoring.

Carvalho has said this kind of tutoring also is ramping up.

Los Angeles Unified Supt. Alberto M. Carvalho has a high-voltage style and ambitious agenda, although it’s too soon to gauge his success as students struggle with pandemic setbacks.

Across the country, extended learning opportunities of any sort appeared to have been limited — compared to the need.

“We are seeing that not many kids have been getting the kind of help in the regular school day that would best help them catch up,” said Robin Lake, director and professor of practice at the Center on Reinventing Public Education at Arizona State University. “So the logical conclusion is that districts have to turn to out-of-school learning time. But that is tricky for the reasons you are seeing in L.A.: union contracts; teacher resistance to working longer hours; student resistance to staying longer hours, etc. And it is no guarantee that kids will learn more.”

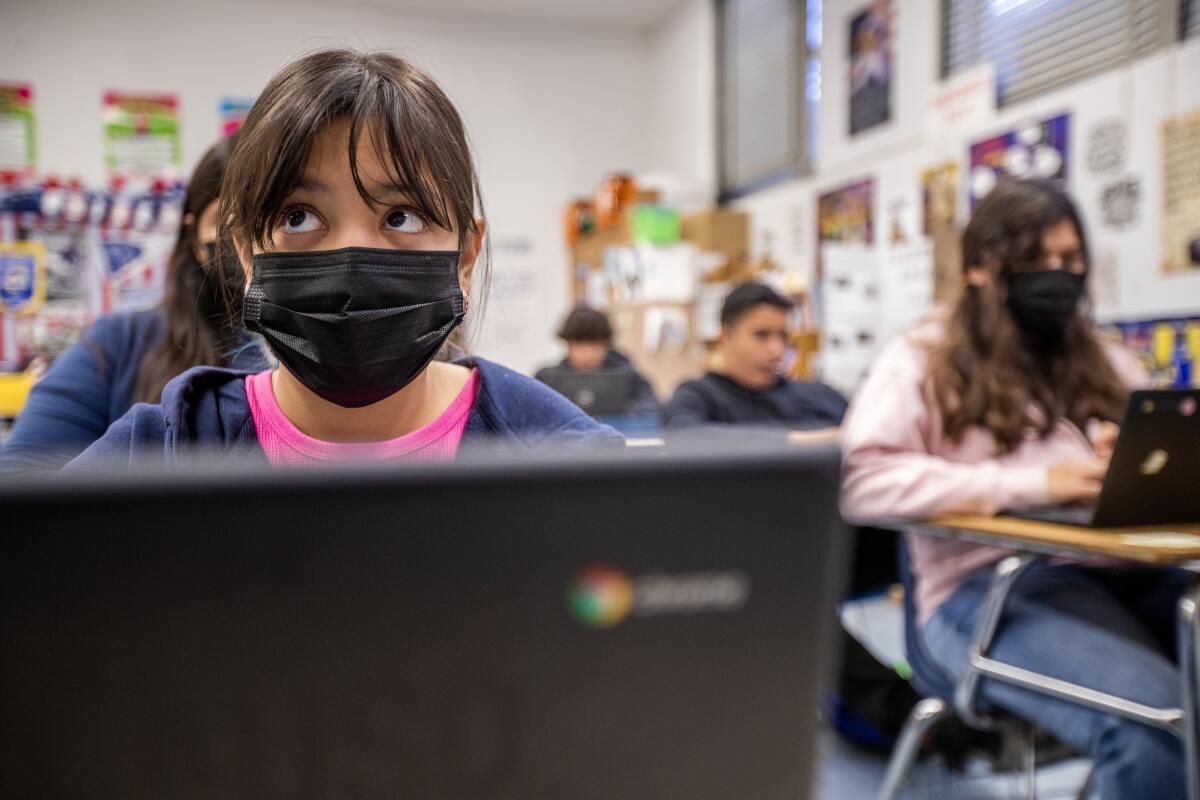

For students anywhere, the standard playbook for academic recovery includes focused tutoring, extended instructional time and mental and emotional support. The program last week at Griffith STEAM Magnet Middle School in East L.A. tried to hit all those points and more.

One important element for successful academic support is small group size.

There were 11 students in Escalante’s class on the second acceleration day — compared with more than 150 over six periods in her typical schedule. Across the district, the ultra small class size was not entirely by design. More than 40% of those registered did not show up, according to L.A. Unified — similar to what happened in December.

At Griffith, 385 students enrolled and 244 attended on the first day. Another 32 arrived without having registered — for a total of 276. The second day total was 216, including five new arrivals who had not registered.

All 11 students in Escalante’s Room 801 were students she teaches. She’s had some for two years. Such familiarity is another feature of successful extended learning. Moreover, every student in Escalante’s class was working online on individualized assignments provided by their various teachers that could be completed to raise grades.

Such individualization was not the case at all schools. This time — like last time — teachers reported last-minute additions of unfamiliar students to rosters as well as a shortage of up-to-date academic data. Many teachers provided general lessons that were appropriate for the grade level, but not designed to address a particular student’s needs.

“My elementary school had 64 of 194 students show up,” said a teacher from an elementary school in Reseda. “We had about 30 to 35 adults on campus for the students.” And while the adult-to-student ratio was remarkable — and students took part in activities they enjoyed — “today did not help learning loss,” the teacher said. “It was work that everyone could do. Biggest waste of funds ever.”

Some families reported even worse — little learning, little that was enjoyable. But many parents and teachers felt just the opposite.

A dozen community groups have signed onto mentoring effort, for which L.A. Unified will provide an organizing hub, including background checks of mentors.

In Escalante’s class, seventh-grader Dylan Camacho, 13, pulled up his history grade from a D to an A while working online. He’d done so by compiling information about Mayans and Aztecs. He’d needed to recover from a disastrous group project, he said, where not everyone had turned in work, but all had received the same grade.

Students were not necessarily working in an area of Escalante’s expertise. But she could direct them as needed to online, on-demand tutors available for live chat with an online whiteboard to write things out.

Such “just in time” tutoring can work well, experts say.

For many middle and high schoolers, the accelerations days were transactional: Do an assignment; get a grade boost. Experts have questioned how deep the learning goes in such situations.

Following the December acceleration days, officials reported 7,812 improved grades after the traditional close of fall semester grading. About 220 high school grades jumped three or more levels — from a D to an A or from an F to an A or B with the one or two days of attendance and work. However, it’s unclear how much difference the acceleration days made when compared to past years, when there were smaller-scale, more-targeted special sessions during breaks, online credit recovery and credit for last-minute assignments accepted after the end of term. The district did not undertake that level of analysis.

“I worry that pandemic relaxation in grading standards — which may well have been appropriate — has continued and is now a problem,” Goldhaber said. “In particular, I’m worried that parents may not have a good sense of whether their kids are behind and need interventions, like extra learning time, because they see their kids getting good grades, even if those grades aren’t all that representative of the state of learning/knowledge.”

As a break from the desk work, about one in five of the students at Griffith spent a portion of the second April acceleration day working in the school’s garden, an activity led by Christine Mariano, the school’s psychiatric social worker. Attending to social emotional well-being can be another aspect to successful academic recovery, according to experts.

The students seemed to know what to do without being told: attacking weeds in about 30 planters; gently prodding sunflower seeds into damp soil; watering produce beds brimming with chard, lettuce, cilantro, tomatoes and strawberry plants.

Sixth-grader Yarely Perez, 12, said pulling up weeds is hard, but “really good for your mental health. Just looking at the garden just makes you feel like you’re at peace.”

Another sixth-grade gardener, Briseida Aguilar, 12, said she’d just be sitting at home, bored, if not at school. And she’d pulled up her grades from Ds and Fs to mostly Bs.

Several students spoke of being better able to focus on this quiet, simple school day than in the bustle of having seven 43-minute periods and having to keep up with assignments in all their classes.

“It’s much easier,” said Rebbeca, who said she hoped to pull up her Fs to Bs and Cs.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.