Deputies outlined veiled threat to county watchdog on defaced poster. Nothing happened

- Share via

Last fall, investigators with the Office of Inspector General — the county’s watchdog — paid a visit to the troubled East Los Angeles sheriff’s station, home of the notorious Banditos deputy gang.

While walking through the station, one of the investigators spotted something shocking: a poster featuring her boss, with words that seemed like a death threat.

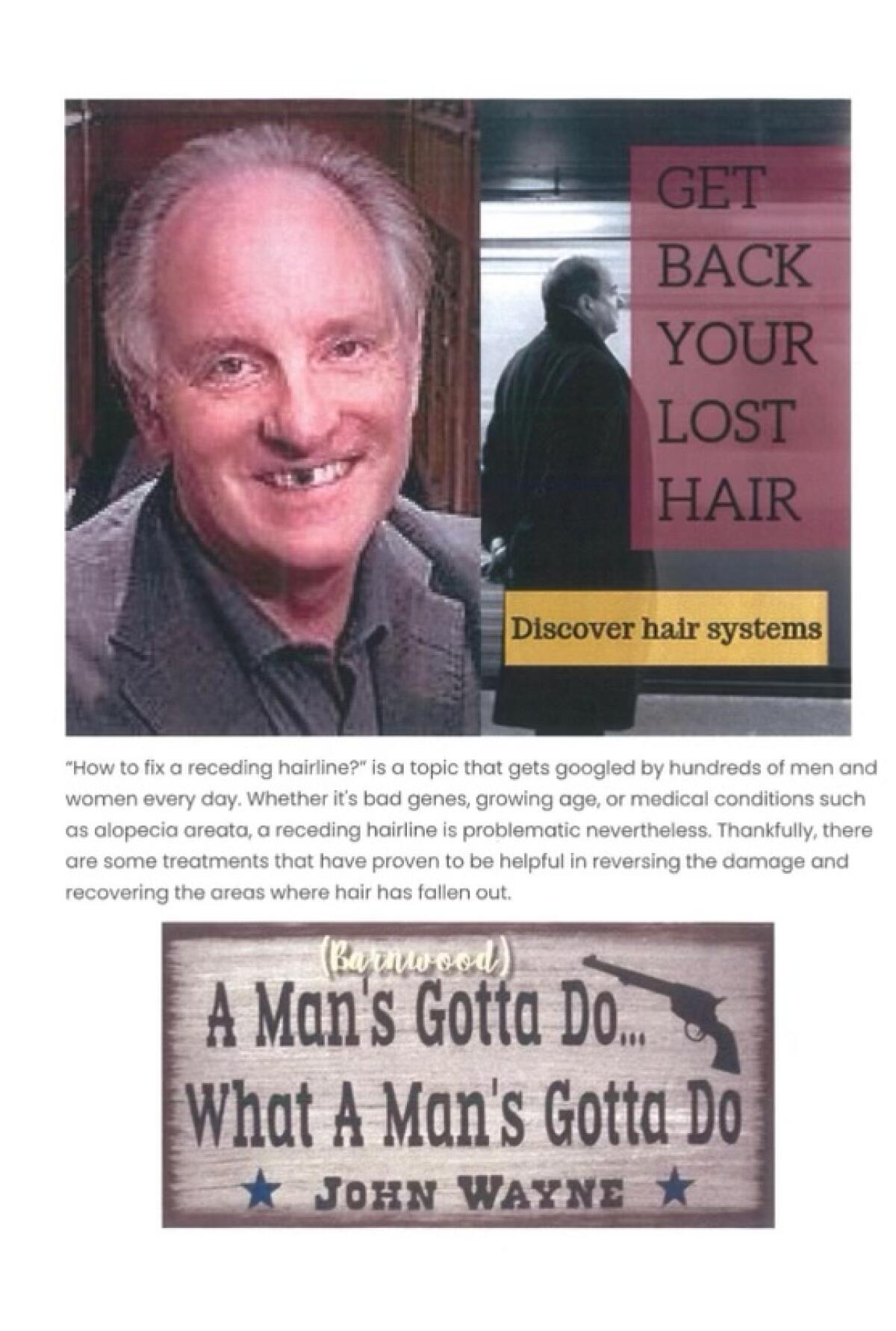

Someone had inserted a defaced picture of Inspector General Max Huntsman onto a fake hair loss ad, along with a quote attributed to John Wayne: “A man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do.”

Next to the saying was the outline of a gun.

“That was in the Detective Bureau for all to see,” Huntsman told the Civilian Oversight Commission on Thursday. “My staff brought it to the Sheriff’s Department’s attention. So far the amount of Internal Affairs investigation conducted on that is zero. And it’s been six months.”

Despite that, Huntsman said, the captain who oversaw the station was allowed to remain in place until this month — after The Times uncovered a memo accusing her of scheming to avoid promoting a sergeant she allegedly saw as an “angry Black.”

“Again: no response, no movement, no action until it was on the front page of the paper,” Huntsman said. “That is the way the Sheriff’s Department currently conducts its Internal Affairs investigations. It is unacceptable. It is not an improvement from the days when we had a sheriff who was figuratively — almost literally — gunning for people.”

Though the new administration of Sheriff Robert Luna has shown signs of change — such as ordering deputies to cooperate in an ongoing OIG investigation into deputy gangs — Huntsman said the department as a whole has not.

“The orders are different,” Huntsman said, “but the organization has not had a sea change in its culture.”

The Sheriff’s Department representative who was present did not address the allegations about the threatening poster, although a day later the department confirmed to The Times that officials had opened an investigation into the matter last year and that it has not yet been completed.

Given the amount of time that has passed without any apparent action, Huntsman said the incident stood as an example of the department’s poor track record of investigating itself — both under current and former administrations.

But the issue that made that track record the focus of Thursday’s heated meeting was the investigation into the highly publicized 2020 killing of 18-year-old Andres Guardado.

That June, Deputy Miguel Vega shot Guardado in the back five times following a brief foot chase in Gardena. Vega and his partner Deputy Chris Hernandez said the teen was reaching for a gun, though one witness later disputed that. The gun authorities recovered was found five feet from his face-down body.

Guardado’s killing led to widespread protests and a lawsuit filed by his family against the county that was settled for $8 million. This year, both deputies were indicted in an unrelated federal case involving the alleged abduction of a skateboarder; the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office had declined to prosecute them for Guardado’s killing.

Still, many unanswered questions remain — including whether either Vega or Hernandez was involved in a deputy gang and why the two Sheriff’s Department detectives who probed the teen’s killing later asserted their 5th Amendment right against self-incrimination when publicly questioned about their handling of the case.

During a coroner’s inquest, both investigators refused to answer even such basic questions as how long they’d been working as detectives, what training they’d done and whether they had handled the Guardado case at all.

“These two detectives asserted the 5th Amendment without any explanation,” said commission Chair Sean Kennedy. “My question is: How can this commission, and more importantly the public, have any confidence in the Sheriff Department’s investigation and conclusions in light of this assertion?”

Assistant Sheriff Holly Francisco admitted the department’s investigators never asked Vega and Hernandez whether they belonged to a deputy gang, and she said Luna and the department shared the commission’s concerns about investigators pleading the 5th Amendment.

Now, she said, the department has a policy to remove investigators from a case if they do that.

“Moving forward, if investigators feel the need to take the 5th on any investigation, those investigators will be removed from the case and new investigators will be assigned the case,” Francisco said.

That policy change did little to placate members of the commission, who called the investigation “inadequate” and also questioned why the sheriff hadn’t yet implemented any of the 27 recommendations the oversight body issued more than two months ago in a report condemning the “cancer” of deputy gangs and urging the sheriff to create a policy officially banning the secretive groups.

The lengthy report offered a range of suggestions, including firing captains who won’t support anti-gang policies, requiring deputies to hide any gang-related tattoos at work, notifying prosecutors whenever a gang-involved deputy is set to testify as a witness in court and holding community meetings.

But as of now, commissioners pointed out, the department has not even implemented the most basic recommendations such as explicitly banning gang membership.

“We’d like to see some action here, some leadership,” commissioner Robert Bonner chided.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.