Whistleblower loses $26-million lawsuit over ‘Executioners’ deputy gang

- Share via

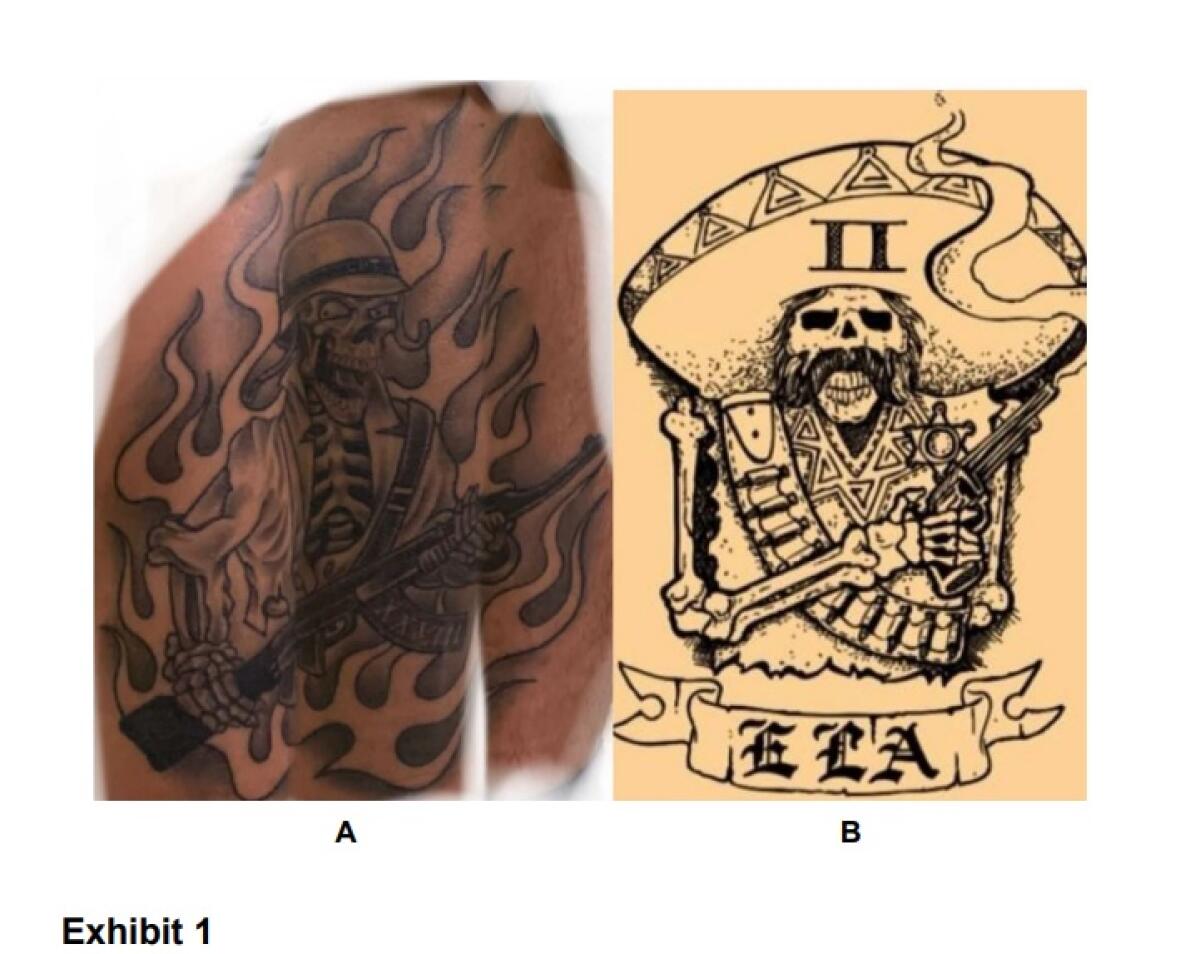

The testimony was alarming. For more than two weeks, jurors heard about deputy gangs, saw their tattoos and logos, learned about their inking parties and listened to witnesses talk about members’ alleged control over the sheriff’s station in Compton.

At one point, a deputy pulled up a pant leg to reveal a tattoo of a flaming skeleton gripping a rifle.

But ultimately, none of that mattered: The lawsuit itself — a $26-million whistleblower retaliation claim — was not about whether deputy gangs exist within the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, but whether one man’s opposition to the so-called Executioners was the reason he couldn’t get a coveted promotion.

In the end, the jury said it wasn’t.

On Friday morning, after less than a day of deliberations, plaintiff Lt. Larry Waldie walked away from court empty-handed. All 12 jurors agreed he’d acted as a whistleblower. But they also agreed it was unclear whether that whistleblowing activity was the reason he lost his bid to become the permanent captain of the Compton station.

“We disagree with the jury’s decision, but we respect it,” said Alan Romero, the attorney who represented Waldie. “We are going to avail ourselves of all appropriate remedies under the law.”

Officials with the Sheriff’s Department said in an emailed statement Friday that they were pleased with the outcome.

“However, it does not diminish our commitment to eradicating deputy gangs and ensuring accountability in our Department,” the statement said.

Similarly, a spokesperson for the county lauded the jury’s decision, calling Waldie’s allegations “unfounded” in a statement sent late Friday.

“While this particular case has concluded, deputy gangs remain a reality in the Sheriff’s Department,” the county’s statement said. “Both the Office of Inspector General and the Civilian Oversight Commission have active investigations into deputy gangs that are intended to help eradicate them, and we look forward to their findings.”

During the trial, lawyers for the county repeatedly pointed out that Waldie bore the tattoo of another deputy group — the Gladiators — and painted him as a disgruntled employee unhappy he’d been denied a promotion.

“He is not a whistleblower,” attorney Avi Burkwitz said during closing arguments. “If anything, he swallowed the whistle.”

Reports of violent and secretive cliques of deputies have plagued the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department for half a century and led to an array of investigations, studies and legal settlements.

In March, the Civilian Oversight Commission released a 70-page report condemning the “cancer” of deputy gangs, saying they “create rituals that valorize violence, such as recording all deputy-involved shootings in an official book, celebrating with ‘shooting parties,’ and authorizing deputies who have shot a community member to add embellishments to their common gang tattoos.”

But before the Waldie trial began, Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Maurice Leiter banned the mention of various deputy shootings and oversight investigations, so the court did not hear testimony about the groups’ alleged links to violence.

Still, the case pitted two groups of tattooed deputies against each other, and those groups were the focus of some of the most explosive testimony.

A new report by the Civilian Oversight Commission condemned the “cancer” of violent deputy gangs in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and urged a ban on the secretive groups.

Some witnesses named all the deputies they’d seen sporting the groups’ tattoos. One witness, Deputy Jaime Juarez, described the inking party in Pomona where he got his own tattoo and said he’d later helped decide which deputies would be invited to get a tattoo like it.

Last year during depositions, Juarez refused to answer questions about his tattoo, following the advice of county counsel. But during trial, in addition to showing his ink, he explained some of its details.

Specifically, he said the tattoo was a “positive thing” and that its design included the number 18 because he was the 18th person to get that tattoo. In total, roughly 40 deputies have the same tattoo, he said, adding that no one has a full list of them. He also said the group — commonly known as the Executioners — has no official name.

The case that led to the weeks-long trial began in 2020, when Waldie alleged he was demoted after he “openly opposed” the Executioners’ control over the Compton station while he was acting captain there.

Waldie — whose father was once an undersheriff in the same department — had been working as the operations lieutenant at Compton station for several months when he took over as the acting captain in January 2019.

At the time, Juarez was the Compton scheduling deputy, which gave him power in choosing the training and vacation schedules for others at the station. In early 2019, he approached Waldie with a list of other possible deputies he wanted to take over the scheduling position.

But Waldie said he believed Juarez was a tattooed member of the Executioners, and he wanted a new scheduling deputy who was not.

So he refused the request, instead giving the position to someone who did not have any gang tattoo. In response, Waldie alleged, Juarez retaliated by initiating a “work slowdown” at the Compton station. When Waldie complained to higher-ups, he said, Juarez was moved to another station for a few months.

Last year, during testimony given under oath as part of the Civilian Oversight Commission’s investigation that led to the 70-page report released in March, then-Chief April Tardy seemingly confirmed that narrative.

At the time, Tardy — who is now the undersheriff — said she had moved Juarez to a different station “because of the information that I had received about the work slowdown.”

She went on to testify that she’d confirmed Juarez had initiated the work slowdown in response to Waldie’s refusal to install the scheduling deputy Juarez wanted.

But during trial this week, she walked that back, saying that she’d misspoken and that she meant to say all the information she’d received was only unconfirmed allegations.

“When I testified, I just didn’t say the word ‘allegations,’” she told the court.

In an apparent change of course from her sworn statements last year, Undersheriff April Tardy testified Tuesday there was no work slowdown led by deputy gangs at the Compton sheriff’s station in 2019.

Lawyers for the county sought to show this week that there had been no 2019 work slowdown at all, saying the decrease in arrests was only minor. Figures presented Tuesday showed that the Compton station’s arrest numbers in March 2019 — the month of the suspected slowdown — were noticeably lower than the February 2019 numbers but only slightly lower than the March 2018 numbers.

Waldie maintained that those same numbers showed there was a work slowdown and that he felt the repercussions for reporting it when he applied to be the permanent captain at Compton in mid-2019.

Even though he’d been the acting captain for several months by that point, he was eliminated from consideration so quickly that he didn’t even make the top 10 candidates. His lawyer, Romero, argued that was an act of retaliation for complaining about gang activity.

Lawyers for the county told a different story, aiming to prove that Waldie was simply not the most qualified candidate and that he’d moved up the ranks with unusual speed because of his father’s position in the department. They also pointed out that Waldie, too, belonged to a tattooed group. And they alleged he’d promoted or given special assignments to people who were fellow members of that group.

After both sides wrapped up closing arguments late Thursday, the jury began deliberations and came back with a verdict mid-morning Friday. Moving forward, Waldie’s attorney said, he will likely file a motion for a new trial and an appeal.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.