E. coli hammers a California town, sending patients to ER and shutting down restaurants

- Share via

BURNEY, Calif — Maria McCloud’s 1-year-old granddaughter got sick first — vomiting and diarrhea and a fever.

A few days later, McCloud began to feel ill, as did several other children in the home.

Probably the stomach flu, the family figured.

And then they got a notice from the water district in this Northern California mountain town: E. coli had been found in the water supply.

It was at that point that McCloud — still feeling nauseated —piled the vomiting baby and several other sick children into the car and made the 20-mile drive to the hospital in the nearby town of Fall River Mills.

Once there, a test soon confirmed that she and her baby granddaughter had E. coli too. And, McCloud said, a doctor told her that numerous patients from her small town had shown up with stomach ailments.

Valerie Lakey, the chief public information officer for the Mayers Memorial Hospital District, said the hospital had treated four patients with confirmed cases of E. coli, and that other patients may have presented with symptoms but not been tested.

She added that the hospital district, which also operates a skilled nursing facility in Burney, found out about the E. coli in the water from a notice posted on Facebook, and not from a direct notification from the water district.

“At times like this, communication is important,” Lakey said. But she said that officials saw the notice almost immediately and quickly took action to protect residents.

But McCloud said she wished her family had known sooner. “I’m mad; I’m watching all our kids be sick,” she said. “I don’t understand why they didn’t catch it sooner.”

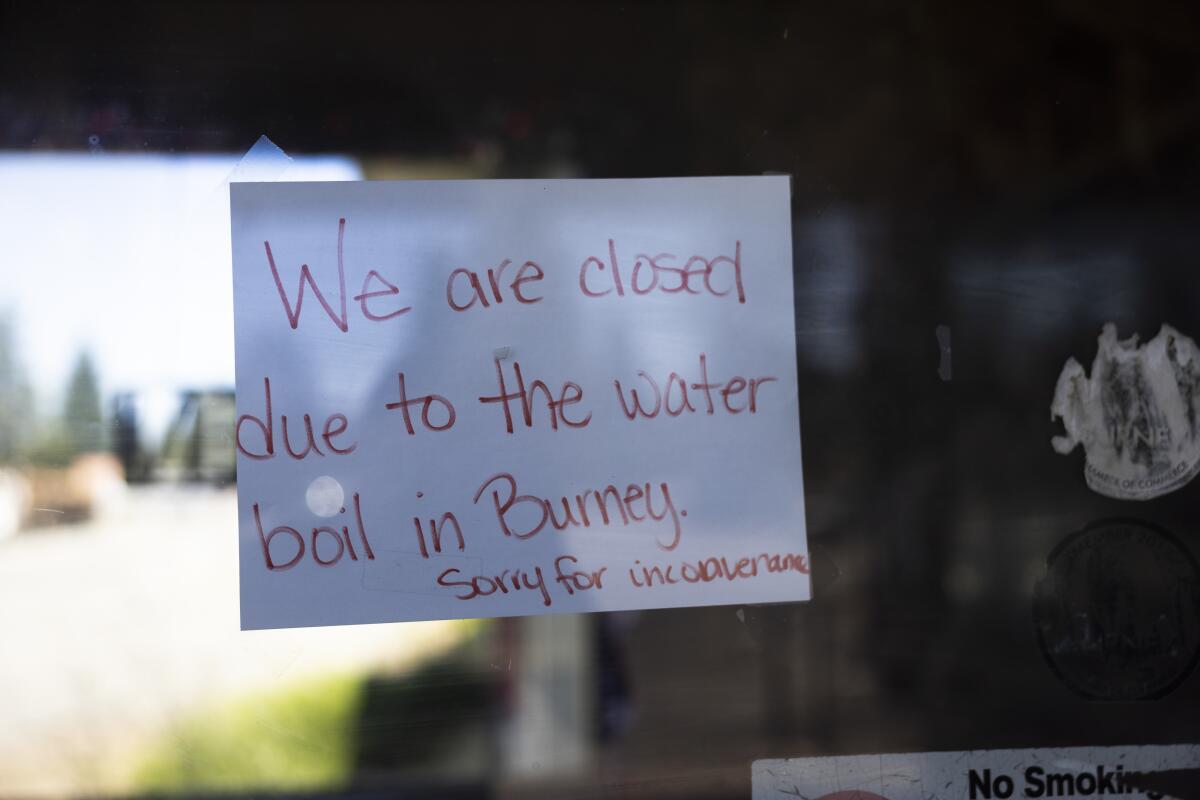

Now, one week into the crisis, it’s almost impossible to find anyone in Burney — an unincorporated lumber and tourist town of just over 3,000 residents near the Instagram-famous Burney Falls — who doesn’t know about the problem. Everyone is struggling to get through their days without potable water as the local water district works to treat the source of the problem. Restaurants that rely on tourists have shut their doors.

It is yet another example of the vulnerability of rural California’s water systems. Many of the state’s failing water systems are in the Central Valley, where water is drawn from wells that are contaminated with nitrates, or that have run dry because of years of drought and overpumping of groundwater. The irony is, Burney, nestled near the snow-capped peaks of the northern Sierra Nevada mountains and surrounded by cool rushing streams, usually has some of the cleanest and most delicious water in the state, according to residents.

But not this month.

On July 12, the water district posted a boil water notice on Facebook. In the following days, officials went door to door posting notices warning residents not to drink the water and telling restaurant owners they had to close.

It was a heavy blow for businesses that rely on summer tourist traffic to buoy them through leaner winter months.

“It’s terrible,” said Connie Voltura, the owner of the Rex Club, a restaurant and banquet hall on the town’s main drag, State Route 299. The Rex Club also operates four cabins, and she said guests canceled their reservations when they discovered the lack of water.

“We’re in our peak tourist season right now,” she said. “We rely on tourists in the summer, so we can make our money, so we can make it through the winter.”

“I can’t take this for very much longer,” she added.

Nancy Bobo, the manager of the Green Gables Motel, said some of her guests also left early upon learning that they couldn’t drink the water and that the motel can’t even hook up its coffee maker in the morning. But Bobo said the real hardship is being borne by restaurant workers, who were sent home, until further notice, many of them without pay.

Up and down the town’s main street, restaurants with empty parking lots have remained dark for days. At the McDonald’s on the north end of town on a recent evening, a car entered the drive-through. The driver rolled down their window and spoke plaintively into the microphone. After receiving no response, they slowly drove away.

The local Safeway — which serves as the town’s de facto public square, especially in the hot summer months — is seeing a run on prepared meals. Residents pushed carts full of cases of water and frozen food. Some residents stopped to compare notes about who had fled town until the water was better and whether it was safe to take a shower.

“Can’t do nothing about it,” said one woman who has lived in Burney since 1962 and declined to give her name because she said she wanted to protect her privacy. Her cart was full of frozen food. “It’s inconvenienced everybody,” she said.

Rumors have abounded around town as to the cause. Some said a raccoon had sneaked into the water tank and died there. Others said they heard a water line had somehow been shot through with sewage.

David Zevely, the manager of the Burney Water District, said officials had not yet determined the cause. Routine testing detected the pathogen on July 12, he said. Illnesses from E. coli bacteria generally strike three to four days after contact. Symptoms include diarrhea, severe stomach cramps and vomiting, according to the CDC.

On July 14, technicians added sodium hypochlorite to the water system to disinfect it — something many residents said they could have figured out even without the post from the district because the smell of chlorine began to waft from their taps.

The water system will be monitored for a few days, according to a notice on the district’s website, and then chlorine will be flushed from the system. More testing will follow and then, after approval from state drinking water regulators, the boil water advisory may be lifted.

Steve Watson, Lassen County’s district engineer for the state’s drinking water division, said investigators still have not determined what caused the contamination. But “the good news,” he added, is that the wells that the district draws water from show no signs of E. coli . “What we do know is it is not a problem with their source.”

Once the boil water notice is lifted, he said, the water district will do extra testing to make sure the problem has been resolved.

As her family recovers, McCloud said she fears the contamination may have been present for longer than the district realizes.

In all, she said eight members of her family became ill. She also said that many out-of-town visitors who came up for the July 4 weekend experienced what they thought was stomach flu.

In addition, she said, several of her mother’s neighbors, who live in housing for elderly members of the Pit River Tribe, became ill.

The tribe, and others in the area that operate casinos, dispatched cases of bottled water to be donated to residents. She was thankful, but also wondered why the water district failed to provide drinking water.

Thankfully, McCloud said, everyone in her family is feeling better, although some of the children are still fatigued and complaining of periodic nausea.

But she said she is still traumatized to think of all the tap water she pressed upon the children when they started feeling poorly, believing that fluids would help.

“This is usually good drinking water,” she said. But it was “making them sicker and sicker.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.