How Asian-language tattoos have helped me feel at home in my own skin

- Share via

The Chinese language is difficult, and perhaps no one has struggled more with it than the inkers and bearers of America’s Chinese-character tattoos.

Most infamous was probably the tattoo on Britney Spears’ hip, which intended to be the character for “mysterious,” but ended expressing something closer to “strange.”

Another popular choice is the Chinese character for “freedom,” which mistranslates to mian fei, or “free of charge.” I’ve also seen tattoos intended to represent the Chinese character for “power” represented as dian, which means “electricity” rather than “strength.”

I got my first tattoo in 2014 at My Tattoo in Alhambra, a road map of Los Angeles in black and red. My second came from a tattoo parlor in a neon lit alley in Shihlin Night Market in Taipei, a Chinese family stamp that depicts the meaning of my last name, a bear.

Each tattoo attempts to express something different that is important to me, and I often considered using Chinese. But I could never see the Chinese character tattoo as anything more than an embarrassing stereotype. I associated it with exoticizing Asian culture, robbing it of meaning, except as decoration. I joked that getting one might pigeonhole me as one of those guy who owns one too many kimonos.

There’s probably no need to get this tangled up over a tattoo. But I don’t think I’m alone. Asian Americans often grow up with mocking, racist or alienating representations of our culture. And sometimes that has the ironic, contradictory effect of making us feel stereotyped by our own cultures.

Mainstream culture’s version of Asian American identity can feel like a costume you never agreed to wear. To construct an identity that could contain all parts of myself, I felt like I had to shed that skin and create some distance from it.

Now, conical rice paddy hats, the sound of a gong, and kung-fu have all become things I find very hard to enjoy or appreciate. These basically harmless aspects of Chinese cultures, through the lens of past pain, can still hurt.

When I moved to Venice Beach two years ago, I saw Chinese tattoos on skaters, lifters, pickleball players, surfers and tourists, hardly any with Chinese heritage. Some tattoo parlors advertised with giant posters of translated Chinese characters in the window. None of them seemed self-conscious or apologetic about it, which made my hesitation feel unnecessary. I envied their nonchalance.

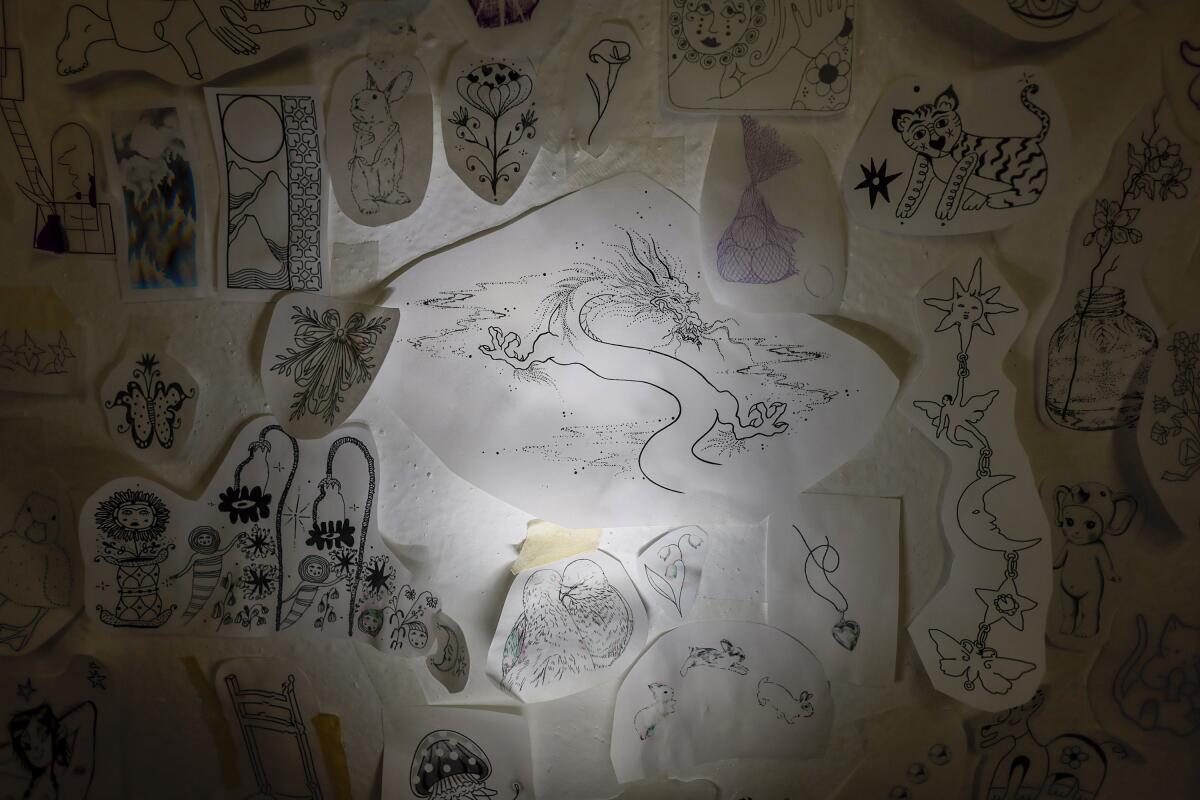

I decided to ink a Taoist verse in a line down my forearm. I met my tattoo artist, Shane, at Devocean Tattoo, a tiny storefront shop. He asked a lot of questions about the characters before getting started — as a white tattoo artist he’s all too aware of the inaccurate Chinese tattoo stereotype.

The pain of a tattoo always seems to land just short of intolerable, depending on where you get it. When the tattoo gun’s twin needles pierce your skin, it stings enough that the body instinctively seeks to stop the pain, whether by flinching or flooding your brain with endorphins. It’s enough pain to frustrate your attempts to avoid thinking about it.

But the most important thing about the pain of a tattoo is that it will end, as with most pain in life. What you’re left with is a feeling of victory over suffering. Or at least, a sense that you have less to fear from it than before. I used to see tattoos as talismans of pain, but now I believe they also represent healing.

When the words on my arm healed, my anger faded with the pain.

There are no easy rules that neatly separate cultural appropriation from cultural appreciation because there is no single way to respect people’s pain. Trying to determine which Chinese-character tattoos are the most authentic or appropriate is pointless, because the most culturally accurate thing to do is to never get one.

Preserving the body is considered an important aspect of filial piety within the context of Confucianism, and that precept encourages long hair, forbids suicide and is interpreted as prohibiting tattoos.

I spoke to a Chinese American tattoo artist, Em Jia, who has a tattoo that plays with this concept. Their mother used to eye Jia’s tattoos with distaste, warning them that all the luck was bleeding out of their body. So Jia inked the words fu chi dou mei you, which means “luckless.”

Tattooing the words was their way of refusing shame and practicing self acceptance, a “way of finding freedom,” Jia said.

But they’re still uncomfortable about seeing Chinese-character tattoos on non-Asian people. They feel protective of their connection to Chinese culture and language. I think it’s a natural reaction for anyone growing up with Long Duk Dong from the 1984 movie “Sixteen Candles” and racist Asian jokes on prime-time TV.

“Now I open a bag of shrimp chips and I don’t give a f— about what anyone says,” said Jia, 26.

Later that day, I met Mike Cho, a Korean American from Philadelphia and the owner of Ocean Front Tattoo in Venice Beach for the last 11 years. Cho said the store experiences steady demand for Chinese tattoos, as does pretty much every other tattoo parlor on the boardwalk.

His skin has enough ink to print a whole newspaper, with tattoos pretty much everywhere but his face. His last name is inked in Korean on his throat, and the Korean characters for the number 17 tattooed on his neck, because he moved to Los Angeles at the age of 21 with just $1,700 in his pocket.

I told him that I wanted to get a Korean word tattooed after traveling to Seoul last year, and wondered what he thought.

At the time I was struggling to find pleasure in food following a difficult breakup. At Gwangjang Market, after I spotted a golden brown seafood pancake sizzling on a flattop grill, I ordered one and devoured it. It was the first meal I remember enjoying in more than a year, and I wanted to memorialize the feeling with a tattoo of the Korean character for “savor,” mas.

Cho, 45, had no problem with me, a Taiwanese guy, getting a Korean character tattoo. Actually, he found the question a bit confusing. He had never thought twice about getting his own Asian-language tattoo.

“Just thought it was cool,” Cho said. “I was more worried about what my parents would say. I didn’t go home for five years!”

I’ll likely meet other Korean Americans who will be bothered by my tattoo. But I can accept that, because I’m trying to imagine a future in which all of these clashing feelings can find some equilibrium. And before pain heals, it has to find expression.

When a tattoo is finished, the area is red, throbbing and swollen. The wound oozes and scabbing cracks the skin. Soon a soft outline of new skin forms around the cuts, peeling and flaking for a while, until one day, you wake up, and there is no scar, just your skin.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.