Avalanches are rarely a danger at U.S. ski resorts. Palisades Tahoe slide was a deadly exception

- Share via

High in the mountains above Lake Tahoe, skiers and snowboarders lined up Wednesday morning to be among the first of the season to ride a chairlift serving some of North America’s most iconic expert terrain. A weekend storm had dumped much-needed snow on the upper mountain at Palisades Tahoe, and more was on the way.

Within half an hour of the lift’s opening, disaster struck.

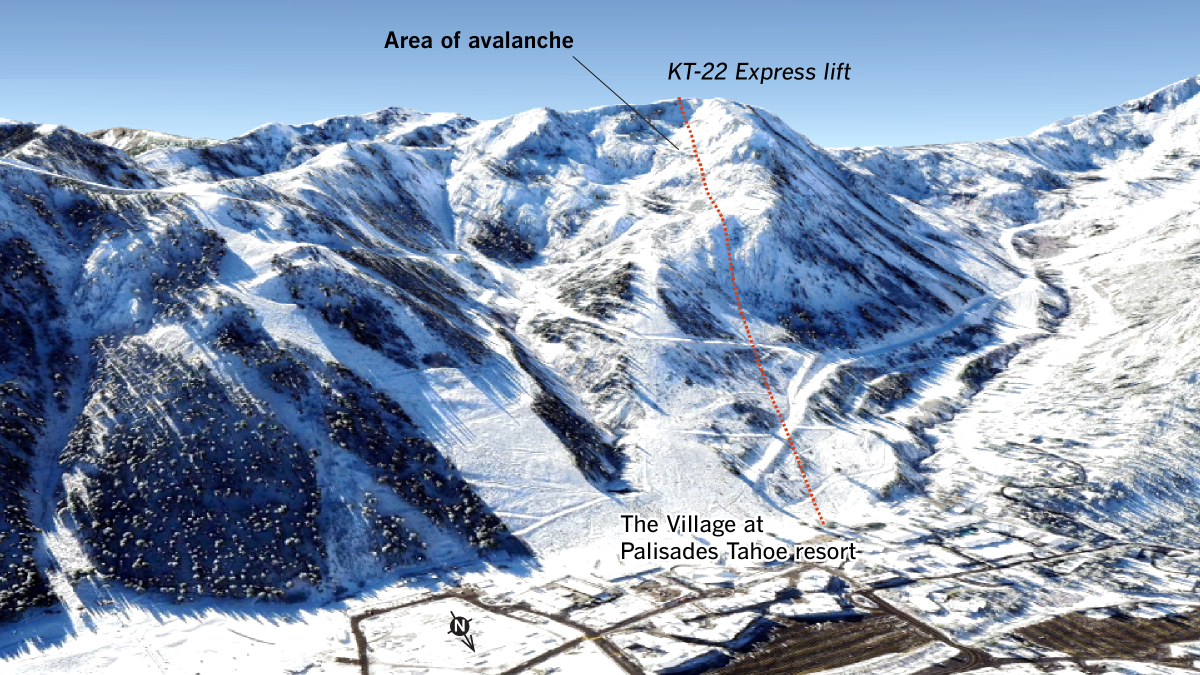

In the newly opened terrain on the peak known as KT-22, an avalanche swept up at least four resort guests around 9:30 a.m. Kenneth Kidd, 66, was killed, and another person who was buried by the avalanche suffered a minor leg injury. Two others were caught in the slide but were rescued by civilians.

Avalanche experts knew the danger Wednesday would be considerable, given the powerful winter storm and strong winds forecast to hit Sierra peaks. But deadly avalanches far more commonly strike in the backcountry, not within the boundaries of a ski resort that once hosted the Olympics and boasts robust avalanche operations.

One person was killed and another was injured when an avalanche struck the KT-22 area of the Palisades Tahoe ski resort Wednesday morning, authorities said.

In the last decade, 244 people have died in avalanches in the U.S., according to statistics compiled by the Colorado Avalanche Information Center. The vast majority involved people who were skiing, snowboarding or touring in backcountry areas or what is called “sidecountry” — where they ducked ropes or otherwise wandered beyond resort property into adjacent terrain.

For the record:

5:28 p.m. Jan. 11, 2024An earlier version of this article said eight skiers had died on open resort runs in the last decade. The total is six.

Only six skiers and snowboarders have died in avalanches on open resort runs over the last 10 years. Three of those died in a single 2020 incident at an Idaho resort.

Wednesday’s “in-bounds” avalanche at Palisades Tahoe, as opposed to a slide in the unpatrolled, ungroomed backcountry, was “extremely rare” and caused “so much shock in the industry,” said Michael Reitzell, president of Ski California, the industry association that represents resorts across the state, including Palisades.

“Those are two different things,” Reitzell said. “When you’re in the backcountry, you need a full suite of equipment, and training on how to use that equipment. It’s really important. When you’re inside the resort boundaries, there isn’t some expectation that you’re carrying around a backpack full of avalanche gear.”

After the avalanche struck, more than 100 ski patrolers, rescuers, lift operators, instructors and resort guests as well as rescue dog teams jumped into action, Palisades Tahoe officials said. Video on social media showed people digging others out of the snow.

“Your efforts were remarkable,” the resort said on social media. “It is times like this that show just how deeply we care for one another. Not just at Palisades Tahoe, but in the ski community as a whole. There is comfort in knowing that we can support one another through the worst days.”

The Sierra Avalanche Center, which analyzes backcountry avalanche risk in the Tahoe area, had forecast “considerable” avalanche danger for Wednesday, the third level on a five-point scale. The risk was expected to increase throughout the afternoon and into the evening as the storm mounted.

Two types of avalanches were a concern: “persistent slab” avalanches, caused by weak base layers that can react to new snow on top; and “wind slab” avalanches, which occur when winds move snow into slabs that then collapse into avalanches.

It was not clear what caused Wednesday’s slide, but according to the National Weather Service, about 90% of avalanches are triggered by the victim or someone in the victim’s party.

Though the avalanche danger was considerable, Brandon Schwartz, lead forecaster for the Sierra Avalanche Center, said in an email that the forecast applies to backcountry areas where no avalanche mitigation has been conducted, and not ski areas or highways.

For Palisades Tahoe to open terrain on KT-22 ahead of the projected snowstorm was “absolutely” typical, said Michael Gross, vice president of mountain operations at the resort. Since Sunday, ski patrol conducted avalanche control assessment, including evaluating weather conditions, the snowpack, wind speed and direction, and setting up safety and hazard markings, he said at a Wednesday news conference.

“We’ll evaluate the conditions,” Gross said, “and, based on our expertise and experience and the history, if we deem the conditions safe, we’ll open the terrain.”

Palisades Tahoe, like all Ski California member resorts, uses avalanche mitigation strategies, including explosives or artillery to loosen the snow on the mountain, and “ski cutting,” which tests the stability of the snow, Reitzell said.

“Weather typically is what impacts the chairs more than anything,” he said. “KT-22, being an example of that, it comes up to a peak and exposed area to wind. It usually would close for that type of reason.”

Reitzell said some of the theories being floated as to what caused the avalanche, including the idea that the first group of skiers loosened “weak snow” during the initial runs down the black diamond G.S. Bowl, were “speculation.”

“The avalanche forecasters and the patrolers have a good understanding of what the snowpack is, pretty much down to the surface, where it’s rocks and other things,” he said.

Reitzell reiterated that it is unusual for skiers to face avalanche or other extreme risks on the mountain, even though it is inherently a more dangerous sport.

“There are risks, and injuries do occur when you’re out with your skis and your snowboard and you’re trying to slide down a mountain at anywhere from 6,000 to 10,000 feet,” he said. “While that risk is always present, we really do want to assure people this is not something that’s common at all.”

The recent barrage of snowstorms, coupled with the fairly dry winter the western U.S. has had up until this point, has created widespread avalanche hazard across the country, said Simon Trautman, director of the National Avalanche Center.

This is the first time since 1992, he said, when the first death caused by an avalanche in a winter season has happened after Jan. 1.

“That points to how dry it’s been to a large area,” Trautman said. “What happens is any snow on the ground becomes very weak and is a [poor] surface for new snow to fall on.”

Wednesday’s slide came hours before one of the strongest storms to hit California so far this season dumped snow across the Sierra Nevada. About 20 inches had accumulated at the base of Mt. Rose as of 7 a.m. Thursday, according to the National Weather Service. Palisades Tahoe got 14 inches of snow at the upper mountain and 7 inches at the base. The storm also dropped 6 inches on Homewood, 21 inches on Heavenly, 11 inches on Northstar and 14 inches at the summit of Diamond Peak.

The weather service said the morning commute was “sketchy to treacherous” across the Sierra, and the Sierra Avalanche Center was again forecasting considerable danger Thursday. “New snow and high winds have loaded existing weak layers” in the snowpack and created the potential for large avalanches, the center said. The continuing high winds could also create slabs of wind blown snow in some areas.

From California to New England to Europe, many areas of the Northern Hemisphere are approaching a ‘snow-loss cliff’ due to global warming, researchers say.

Palisades Tahoe reopened Thursday, though KT-22 remained closed, and resort officials said they lost access to the road to the chairlift because of the avalanche debris, leading to delayed openings.

“It will be a rigorous snow safety morning for both Palisades and Alpine today,” according to the resort’s Thursday operations update. “Since both mountains closed just shy of 11a.m. yesterday, it will take longer to assess all terrain and get everything open. Delays will be more significant than usual. We appreciate your patience and understanding.”

Trautman said a coming storm is just “one metric” of the decision to open a ski area. He said that ski patrol also tends to assess the condition of the snowpack and other variables before deeming an area safe.

“If you’re going through your mitigation strategy and you’re working through the terrain and you decide when you’re done that you haven’t gotten the risk low enough, then you’re not going to open the terrain,” he said. “It’s in nobody’s best interest to do that. Effectively this idea of a storm coming just doesn’t really apply in the short time cycle that we’re talking about. In a backcountry scenario, it’s different because you’re not doing any mitigation.”

On Friday, the avalanche risk is forecast to drop one level to moderate. But another storm is expected to reach the region Friday evening into Saturday, according to the weather service, and a flood of skiers will probably be traveling to the mountain for the three-day holiday weekend. This storm is expected to be warmer, which means there’s a chance of mixed precipitation in the foothills and valleys, and snow levels could be higher, at around 5,500 to 6,500 feet in elevation. There’s a potential for another foot of snow in the Sierra, with 18 to 24 inches forecast along the crest.

Wind speeds could reach around 100 mph in some areas along the Sierra ridge. The weather service issued a winter storm watch until Saturday evening. Roads could become slick and dangerous during the storm, which could affect weekend ski commutes. Visibility could also be low due to blowing snow.

“This storm doesn’t look as strong as the one that just went through, but if we’re going for a boom-bust here, it’s pretty similar to a certain extent,” said weather service forecaster Amanda Young. “We’re still going to get quite a bit of snow in the Sierra.”

Times staff writers David Wharton and Salvador Hernandez contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.