Notorious L.A. gang informant now accused of setting fire that killed 7 children

- Share via

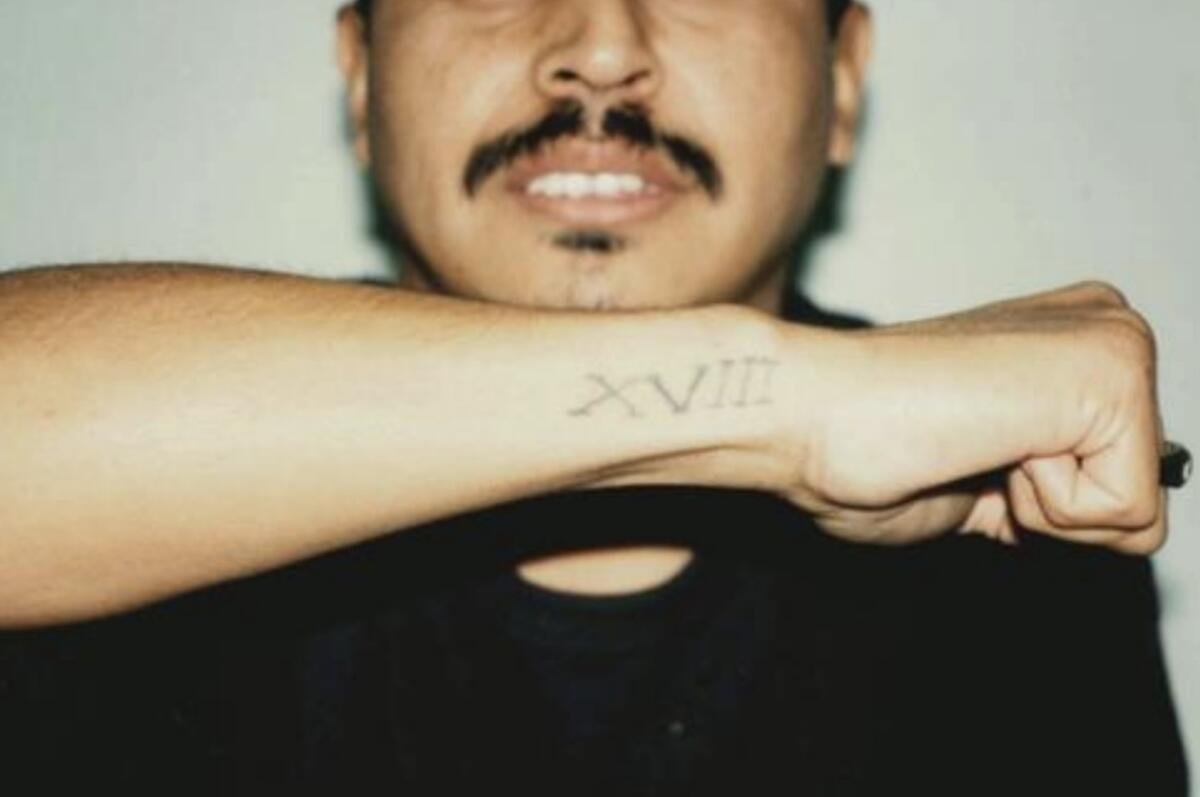

Juan “Termite” Romero was once a leader of the 18th Street gang, shaking down drug dealers on the streets of Westlake in the 1990s. After being targeted for death by his imprisoned boss, Romero became the government’s star witness in a racketeering case that sent dozens of his associates to prison.

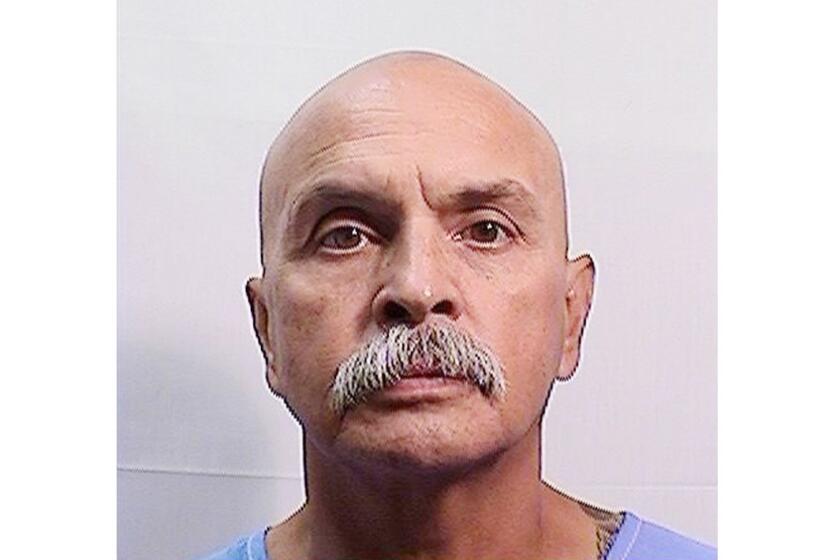

Romero disappeared into witness protection, living under an assumed name far from his old neighborhood. But Los Angeles County prosecutors have brought the 57-year-old out of hiding, alleging he set fire in 1993 to a crowded apartment building, killing seven children and three women, two of them pregnant.

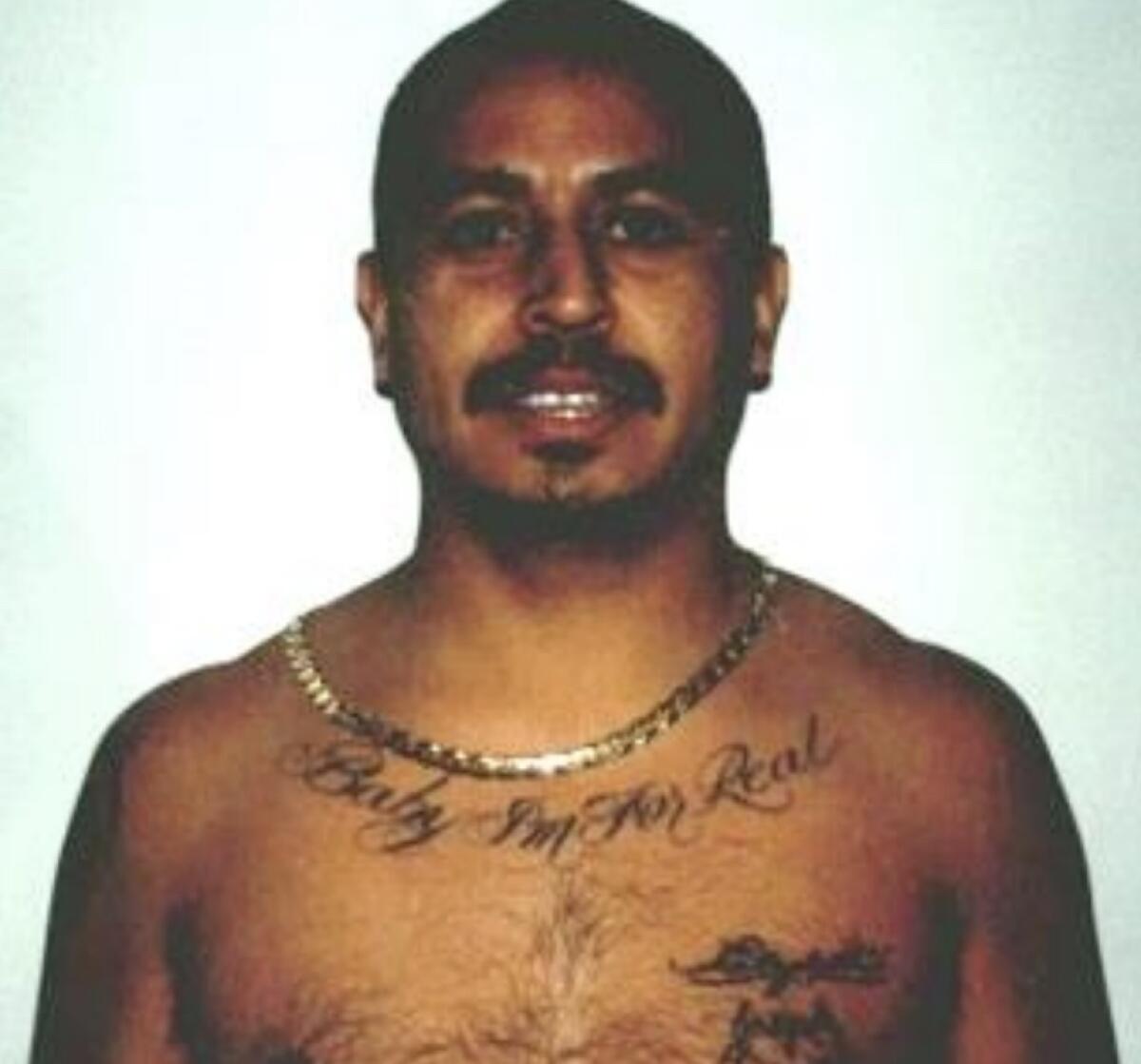

Romero appeared Wednesday morning in a downtown Los Angeles courtroom, where he deferred entering a plea to 12 counts of murder. Dressed in an orange jumpsuit, the short man with thinning hair hardly resembled the gang member who stared into a camera decades earlier, a thick gold chain draped above the words “Baby I’m For Real” tattooed along his collarbone.

The trial of a former L.A. gang member for the deaths of 10 in a 1993 fire was a step back to a time when gangs turned entire blocks into drug bazaars.

The last of four defendants to face charges in the arson, Romero had been a fugitive since 2016, when detectives traveled to the Phoenix apartment complex where he had been living and found that the protected witness had moved just a week earlier. One detective testified she found the timing “incredibly strange.”

Deputy Dist. Atty. Victor Avila declined to specify where or when Romero was arrested, but said he was extradited from Mexico. Records show he was booked into the Los Angeles County jail on Dec. 5.

Daniel Nardoni, an attorney who was initially assigned to represent Romero at his brief appearance Wednesday, said he knew nothing of Romero’s apprehension or the evidence against him.

Romero is accused of setting fire to a three-story, 67-unit stucco building on Burlington Avenue the afternoon of May 3, 1993. Testifying at a trial in 2022, a firefighter recalled people leaping from balconies while paramedics tried to revive others sprawled on the sidewalk. The smoke inside was so thick, he recalled, it was “like being underwater and trying to take a breath.”

Dead from smoke inhalation were Lancey Mateo, 1; Jesus Camargo, 4; Jose Camargo, 4; Rosalia Camargo, 6; Yadira Verdugo, 6; William Verdugo, 8; Leyver Verdugo, 10; Rosalia Ruiz, 21; Olga Leon, 24; and Alejandrina Roblero, 29. Ruiz and Leon were pregnant.

Informants told Los Angeles Police Department detectives the fire was tied to the neighborhood drug trade. Outside the building stood the traqueteros — street-level dealers — who sold crack cocaine and heroin all day and night, according to testimony. The building’s residents, mostly Mexican and Central American immigrants who subdivided units or slept in shifts to save money, couldn’t afford to move.

The attacks demonstrate that MS-13 gangs continue to hold the poorest and most marginalized who live and work in the neighborhood in their grip.

“We all have limitations,” testified one man who lost two nephews and a niece in the fire. “We didn’t earn a lot, so you can only live in a place you can afford.”

For the right to work in this corner of Westlake, a dense neighborhood just west of downtown Los Angeles, the traqueteros paid “rent” to the local gang, the Columbia Lil Cycos clique of 18th Street. So did the mayoristas, or wholesalers, who supplied them.

The mayorista who ran the Burlington Avenue corridor was Johanna Lopez, who testified in 2022 she got her start in the drug trade as a traquetero after immigrating from Honduras in 1990. Lopez was selling cocaine outside the same building that would catch fire three years later when, she said, she was confronted by Romero and another 18th Street member, Ramiro “Greedy” Valerio.

Valerio, testifying at his trial in 2022, said he met Romero after joining the Columbia Lil Cycos at 15. Seven years older than Valerio, Romero bought him clothes and taught him “to dress like a gang member,” Valerio testified.

Valerio said he and Romero collected money from the traqueteros on Burlington Avenue and Bonnie Brae Street and delivered the cash to the wife of their imprisoned boss, Francisco “Puppet” Martinez.

Until his murder in prison two weeks ago, Michael Torres ran one of the most intricate and lucrative black market businesses in L.A. County: the jails.

Lopez testified she paid Valerio and Romero $75 a week to peddle drugs outside the Burlington building. About a year into the arrangement, she said, Valerio and Romero asked if she wanted to move into supplying the traqueteros. Romero, Lopez testified, promised to sell her cocaine on credit at a “good price.”

Lopez agreed. She sold cocaine to 30 dealers who worked in shifts on two streets, delivering the gang’s $4,000-a-week cut to Valerio in a briefcase. To ensure unsanctioned dealers didn’t encroach on her business, 18th Street members patrolled the streets.

By 1993, Lopez testified, she was supplying traqueteros on four streets and kicking up $25,000 a week to Valerio and Romero. In exchange for payoffs, the Burlington apartment building’s manager allowed her dealers to flee inside when the police tried to arrest them.

Then the manager was fired. His replacement changed the locks and reported the drug sales to the police, Lopez testified. With her earnings dwindling, Lopez met Valerio and Romero at a pool hall and asked them to reduce her rent.

Skeptical that sales were down, Romero said he wanted to hear it from the traqueteros themselves, she testified. Lopez, Valerio and Romero walked down Bonnie Brae Street, where the dealers confirmed it. According to Lopez, Romero said he was “going to take care of the problem.”

The day of the fire, Lopez testified, Romero told her: “Better leave here, because this thing is going to get hot.”

Lopez pleaded guilty to two counts of manslaughter and agreed to testify in exchange for a 22-year sentence. She had previously served a 12-year federal term for selling cocaine.

Salvador Granados, a fellow 18th Street member, testified that around the time the fire broke out, Romero, Valerio and a third man called Snoopy burst into an apartment down the street from the burning building, carrying trash bags that smelled like “barbecue liquid.”

Valerio looked panicked, Granados recalled; Romero seemed “upset” and Snoopy was “all red, sweating.” Granados heard sirens outside. As he got up to leave, Granados testified, he heard Romero say, “We f— up. We f— up.”

A terminally ill Mexican Mafia member expounded on the current state of the gang from his prison cell before he was released to die at home.

But witnesses, including Granados and Lopez, waited years to implicate Romero and Valerio in the fire, and only after they were facing lengthy prison terms themselves. Meanwhile, Valerio — and eventually Romero — cooperated with FBI agents and federal prosecutors in a separate racketeering case against 18th Street.

Romero testified against his former boss, Martinez, who was sentenced to life in prison. Valerio, who helped the FBI tape drug deals and introduced undercover officers to gang members, moved out of Los Angeles and found work at movie theaters, a Starbucks and a Rite Aid, according to a letter he wrote to the judge who sentenced him.

In 2013, the LAPD assigned two experienced detectives to revive the 20-year-old investigation. Det. Mitzi Roberts testified in 2022 that Valerio and Romero were the primary suspects, but the FBI had never shared its files on their prized informants with the LAPD.

An FBI spokeswoman in Los Angeles declined to comment.

After requesting the records, “we were met with roadblocks every step of the way,” Roberts recalled, “and it felt — it was very curious to us because we thought this was such a heinous crime and we felt there were deliberate attempts to not allow us access to a lot of the information.”

The FBI eventually turned over several terabytes of data and “stacks of disks” of wiretapped calls involving Valerio and Romero, Roberts testified.

L.A. County prosecutors used the recordings Valerio made at the behest of the FBI to demonstrate he had the authority in 18th Street to order the arson. In one tape, Valerio said, “I was number one with Termite.”

Once prosecutors decided to file charges, Roberts said, she traveled to Phoenix, where the property manager at the complex where Romero had been living told her he’d moved out a week earlier.

Roberts testified that an FBI agent assigned to the investigation had briefed his supervisors about Romero’s planned arrest before they went to Arizona.

In the ensuing years, “we literally went everywhere looking for him, trying to arrest him, from California to Texas. As far as I know,” Roberts testified in 2022, “he is in Mexico.”

Valerio has maintained his innocence. He testified he didn’t set the fire — just watched the billowing smoke in horror like everyone else in the neighborhood — but he was convicted of 12 murders and sentenced last year to life in prison without parole.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.