- Share via

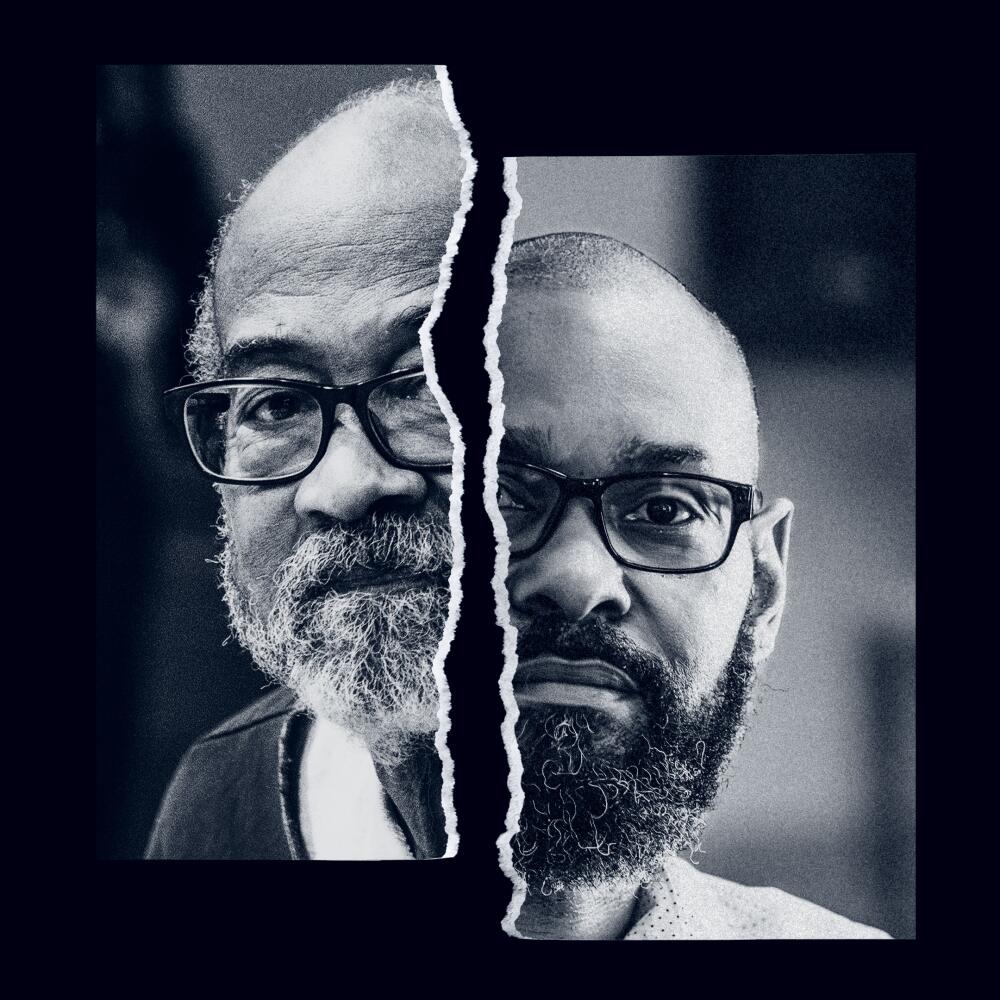

The lawyer insisted that by the time his client got out of prison, he’d be too old to rob banks.

It was 1999, and Bruce Bell’s attorney was arguing for a lesser sentence for the robbery of a Home Savings of America in San Fernando. If the judge sentenced him to 24 years in federal prison — the punishment he had meted out to Bell’s accomplice — Bell would be in his 70s by the time he got out.

“Certainly over any age of the ability to commit any further offenses,” the lawyer told the judge.

Our film editor picks a handful of gems shot in Los Angeles that define the crime film, including classics by Michael Mann, Sofia Coppola and Quentin Tarantino.

Bell was released in 2021 after serving more than two decades. Around two years later, police say, he attempted to rob two banks and stole tens of thousands of dollars from two others.

He was 71. Long past what his lawyer believed was Bell’s prime for robbing banks. And 2021 was many years past the Los Angeles area’s dubious distinction as the “Bank Robbery Capital of the World.”

In 1992, at the peak, there were more than 2,600 bank robberies in the seven-county area covered by the FBI’s Los Angeles field office. There were so many in the ’80s and ’90s that Hollywood took notice, churning out a steady stream of Southern California bank heist movies: “Point Break” (1991). “Heat” (1995). “Set It Off” (1996).

Bell’s partner in crime was a 20-something named Montez Day, who had an earlier bank robbery conviction but who the judge thought might turn his life around. The judge said he wanted to give Day “the basis to hope that there is some opportunity, particularly at your relatively young age.”

When Day got out of federal prison more than two decades later, he seemed to have a far different view of the world than the man with whom he broke the law.

::

Bell grew up in Pacoima, one of seven kids. His parents split up when he was in high school, and his mom went on welfare to try to make ends meet.

His drug habit started young; so did his criminal rap sheet, with stints in juvenile hall for grand theft auto and burglary.

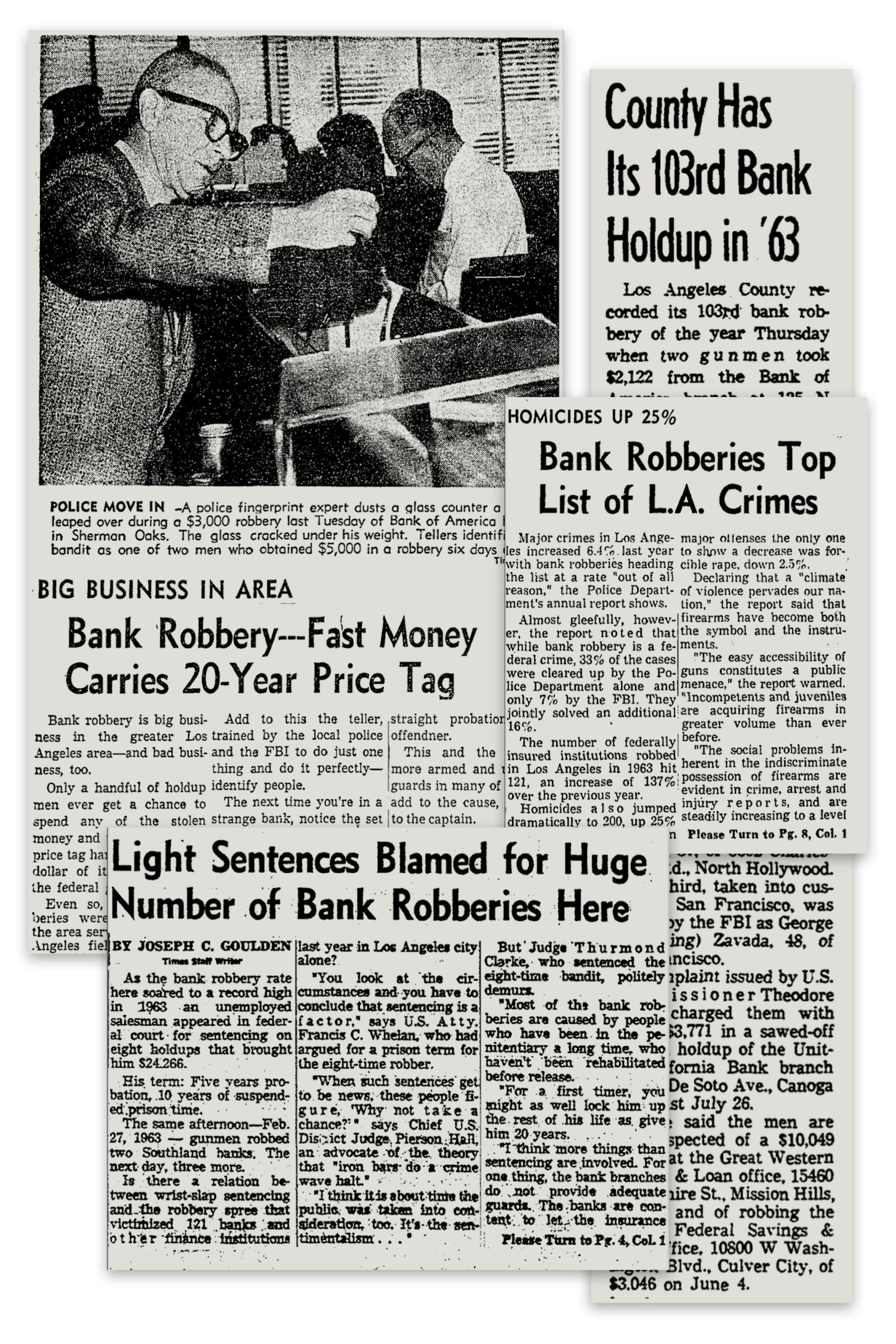

As a kid in the 1960s, Bell started reading about bank robberies in the papers. The stories, he said, read like a how-to guide. And the newspapers printed the take.

“That planted a seed,” Bell recalled.

There were more bank robberies in L.A. than anywhere else in the nation in 1992.

There was the well-dressed man nicknamed the “Calm Bandit” who slid a note to a Bank of America teller: “I have a gun. give me everything. Keep your eyes down.” He made off with around $3,500. The “Sporty Bandit” who wore dark sunglasses as he robbed $1,441 from a bank teller. A mother who left her 5- and 4-year-old children on a bus stop bench while she stole $4,000 from a Bank of America.

Among the accused bank robbers in the ’60s were a 17-year-old girl, men in their 60s and 70s, a former high school class president, an attorney, a surfer (right from the beach), the manager of a championship youth baseball team. Robbers used knives, toy pistols, sawed-off shotguns, bombs and grenades, police said at the time.

By 1963, according to a Times article, L.A. was seeing more bank robberies than any other city in the country. As of that November, robbers had made off with $329,359 in cash from 106 bank jobs — twice as much money and twice as many holdups as the same time the year prior. There was an average of almost one bank stickup every other weekday.

Authorities were puzzled at the jump. The number of banks had not quite doubled between 1944 and 1964, but holdups had soared from 20 in 1945 to 121 in 1963 for the L.A. metro area, according to a Times article.

The FBI director at the time blamed a desire for easy money and a lack of bank security. The wave of crime prompted the agency to host seminars for bank employees on how to give suitable descriptions of suspects and work alarm systems.

Despite the high holdup numbers, L.A. had one of the best apprehension records — with suspects in half of the city’s cases in 1963 arrested, police said at the time. The prison sentences were stringent, in some cases up to 25 years.

“For dollars received and time served it is one of the poorest risks for anyone taking a flyer on crime,” LAPD Sgt. Vance Brasher told The Times in 1963.

But that didn’t deter Bell. Back then, Bell told The Times in a recent jailhouse interview, he didn’t have to worry about security guards or Plexiglas.

“It was so easy, it was almost like a drug,” Bell said.

But in October 1975, the year after Patty Hearst notoriously robbed a bank up north, Bell robbed one in Southern California and got caught. He was 23.

He was sentenced to 15 years but was released to a halfway house in January 1981, according to court records. It didn’t take long for him to become a fugitive.

That April, he was arrested for another bank robbery. The judge sentenced Bell to 25 years for that crime.

As Bell served his time, bank robberies went on unimpeded. The record year came in 1992, at 2,641.

John McEachern, an Alabamian with a Southern drawl, worked the FBI’s bank robbery squad. On his first day in 1996, he recalled, there were 10 bank robberies. The crime was so constant, McEachern said, that a Bank of America teller on Crenshaw had been robbed 13 times.

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The agent’s previous stint on the gang squad meant he was well acquainted with robberies. Gang members opted for a “takeover style,” in which a group would enter the bank armed with guns and “would instill terror,” he said.

McEachern, who worked Rollin’ 60s Crips investigations, recounted the case of reputed gang members Robert Sheldon Brown and Donzell Lamar Thompson. Brown, at just 23, had been implicated in 175 bank heists over a four-year period starting in 1989. Neither Brown or Thompson ever entered a bank, instead using disadvantaged teenagers to commit the crimes.

Two reputed members of the Rollin’ 60s Crips were sent to prison Monday for helping make Los Angeles the bank robbery capital of the world--a feat the FBI says they accomplished by recruiting schoolchildren, arming them with high-powered assault rifles and aiding their getaways with brazen carjackings.

Other robbers, he said, were motivated by drug addiction. He recalled a case of a man in his 70s who went into a San Fernando Valley bank. He didn’t ask for all of the money; instead his note read, “Give me $300.” That’s how much a heroin fix was going to cost, McEachern said.

“I honestly cannot remember ever arresting an individual that had only done one bank robbery,” McEachern said. “If they do one, they’re gonna do another one sooner or later. It was too easy for them.”

::

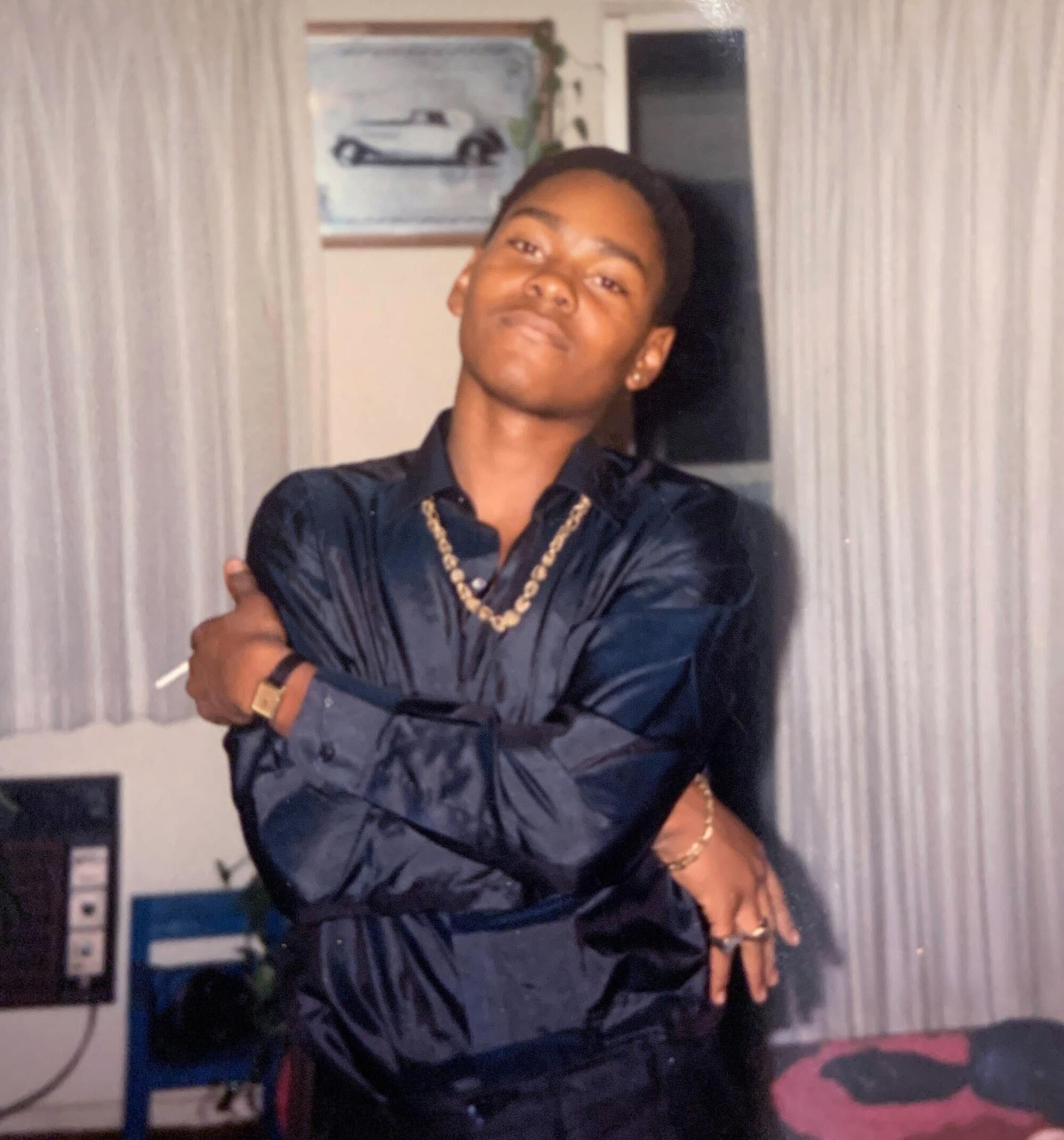

When Bell got out of prison in 1998, he found a partner in Day.

They met, Bell said, through a mutual friend who was in the “criminal element.” By then, Bell was in his mid-40s. Day, who grew up in South Central, was in his late 20s.

Like Bell, Day had had a rough upbringing. When he was 6, his father, who was schizophrenic, murdered Day’s mother. Because of his father’s mental health issues, Day said he only served a few years in prison. After his release, he worked two jobs to try to support Day and himself, often leaving his son home alone.

In eighth grade, wanting money for art supplies and better clothes, Day worked odd jobs. Eventually he started getting paid to ride his bike and buy and deliver crack cocaine. He dropped out of school after he was accused of being a drug dealer.

Day recalled one night when his dad chewed him out for missing curfew.

“‘Man, you can’t even buy me school clothes,’” he told his dad. “‘You can’t even keep food in this house. If the money say I got to be out till two o’clock in the morning, I’m gonna be out till two o’clock.’”

When he was just 15, Day said, he moved into an apartment paid for through drug dealing. Police pulled him over often, hoping to catch him with guns and drugs in his 1977 Oldsmobile Cutlass Supreme Brougham.

After several run-ins with the law, he was convicted in 1992 for possession of cocaine with intent to distribute. After he got out of prison, he said, he stopped selling drugs. Two years later, he was arrested for being a felon in possession of a firearm.

Day’s first bank robbery arrest came in 1994. He was 23, with a pregnant fiancée, rent coming due and $12 in his Wells Fargo account, he later told a judge. Day hadn’t planned on robbing the bank, he said, so he didn’t wear a mask during the crime.

“I don’t even think I got $2,000 from them,” he said.

When he got out of prison in 1998, Day said, it was, “with every intention of being bad.” He started committing white-collar crimes, such as credit card fraud, check fraud, identity theft. Then he met Bell.

On the afternoon of Jan. 26, 1999, Bell and Day entered Home Savings of America, wearing ski masks, according to a San Fernando police report. Bell carried a .38 caliber revolver.

They forced the bank’s assistant manager to open the vault and filled a duffel bag with $85,600. Once outside, they fled in a silver van.

Police spotted the pair switching into a black Ford Expedition parked several blocks away and confronted them, but they sped off — leading the officers on a 20-mile chase. Day, who was driving the car, hit another vehicle. Pursued by police cruisers and a law enforcement helicopter, Day pulled into a shopping center. They were quickly caught.

The men were suspected of two other armed robberies at the same bank the year prior, according to the police report.

“It was their bank,” then-San Fernando Police Lt. Robert Ordelheide told The Times in 1999. “They were just withdrawing.”

Crime: Men surrender after 20-mile chase. Authorities think they robbed the Home Savings branch twice before.

Bell and Day pleaded guilty to the January 1999 robbery.

At their sentencing hearing in October, Day’s lawyer cited his client’s traumatic childhood. When asked if he wanted to speak, Day offered an apology to those he’d hurt. He said he didn’t know how he’d allowed himself “to do something this stupid.”

“He’s had two opportunities to turn his life around in prison and each time all he’s done is get involved in ever-escalating crimes,” the prosecutor told the judge.

Pointing to Day’s age — he was 28 at the time — Judge A. Howard Matz said: “I think that you need to be given a hope.”

When Bell’s attorney, Brian Newman, asked the judge for less time, he talked about his client’s long history of drug abuse. He said Bell had been injured on the job and lost his source of income. The bank robbery, Newman said, “was virtually a spontaneous decision.”

Newman also referenced a doctor’s findings that Bell was immature and “considered of low intellectual function.”

“The report itself makes it clear that, while immature, your client was capable of distinguishing right from wrong,” the judge said.

Bell declined to speak.

“I think that at the age of 47 the lessons of the past still have not been learned,” Matz said.

The judge sentenced Day to 24 years. Bell got more than 26.

::

In prison, including one in Victorville, Bell went to work, making $1.40 an hour through UNICOR, formerly known as Federal Prison Industries. He said he stayed out of trouble and worked nearly seven days a week.

Day served his first five years at a prison in Lompoc, where he recalled teaching a fellow inmate to read. It was the first non-selfish thing he’d done, he said.

“Nothing made me feel the way I felt when I seen him express his joy from reading. ... Me knowing that I helped him, made me look at people and things differently,” Day said. “That’s what made me really start looking at, ‘There’s other things I can be doing.’”

“I believe,” he added, “that there are different catalysts in your life that can shift your mentality.”

After being transferred to a federal penitentiary in Indiana in 2005, Day earned an associate of arts degree. He began teaching continuation classes once a week — an hour of African American history and an hour of psychology.

He became a mentor in a program called STAGES, designed to help people with borderline personality disorder who were using self-harm and negative coping skills to deal with being in prison, according to prison records filed in federal court.

Around 2013, Day signed up for therapy. He said he’d never talked genuinely to a therapist about the death of his mother or the murder of his uncle soon after.

“I started taking care of me my last five years, so that I could deal with having positive coping skills instead of negative coping skills for the trauma that I witnessed,” he said.

In February 2016, he learned that his eldest daughter had been murdered. The following year, in July, his father died. He continued with his therapy.

Day said his biggest motivation to change his life after prison came in the form of his youngest daughter, whom he had begun to build a relationship with a few years earlier.

“It was her that made me say I would never get out and commit crimes. Because she gave me a second chance,” he said. “She said, ‘If you ever go back to jail, I’ll never talk to you again.’ ... All I had was my baby girl. And that’s when I started thinking like, ‘No, nothing’s worth it.’”

In 2019, Day was released from prison after serving 20 years and six months. He was 48 and chose to stay in Indianapolis, where he was born and where his aunt lived. She was his biggest supporter, he said, visiting him every month for 14 years straight. The morning of his release, she was there to pick him up at 7 a.m.

In the months after he got out, Day started attending seminars on reentry and juvenile justice. That led him to Youth Advocate Programs Inc. He served as a mentor for young people on probation.

In 2021, he wrote a letter to a California federal judge, asking to end his supervised release a few years early.

Letters sent on his behalf described him as a “model of successful reentry” and someone who “sets high standards for all of his youth when it comes to manners, accepting responsibility and striving to achieve their goals.”

Day’s probation officer supported his request, and the judge agreed.

::

By 2021, when Bell was released, the number of bank robberies in the L.A. area had plummeted to 54.

McEachern — who supervised the FBI’s bank robbery squad from 2001 to 2006 — credited the drop over the years to increased bank security, a law enforcement crackdown, aggressive prosecution and the rise of cybercrime — where there’s no need for guns or violence. Banks also began holding less cash, he said.

For decades, Southern California was the undisputed capital of bank robbery.

When he was released, Bell said, he had around $12,000 he’d saved working in prison.

After leaving a halfway house in 2021, he said he found employment through a job agency. He worked at a landfill in Sylmar. A Cheesecake Factory bakery. His final job was at a tool and die operation in North Hollywood.

But last fall, police say, Bell started trying to rob banks once more.

His first attempt, according to an LAPD search warrant, came on Oct. 25. That’s when police say a lone man armed with a handgun confronted a security guard outside a Chase Bank in Van Nuys.

The suspect wore a black jacket with an orange stripe and the logo “Joe Boxer,” black reflective sunglasses, black leather gloves, a black cloth cap and black shoes with a yellow stripe across the heel. He carried a grocery style bag printed with images of the Hulk, Iron Man and Captain America, according to police.

“Do what I say,” Bell allegedly said. “No one is gonna get hurt.”

Police said Bell threatened the guard’s life if the tellers didn’t open the security door. The guard managed to flee, and the tellers refused to unlock the door.

On Halloween, police said, Bell tried again — this time hitting a Chase Bank in Panorama City. He allegedly held an employee at gunpoint and demanded entry behind the bank teller security windows. An employee opened the door, but just to pull her colleague inside and lock up. Another failed attempt.

About an hour later, police said, Bell hit a Chase Bank in San Fernando. This time, they said, he got access to the teller booth area and made off with more than $10,000. Based on surveillance video images, police connected the same suspect to all three crimes.

The investigation was still underway when, police said, Bell struck again on Dec. 21 — this time at a Chase Bank in Sun Valley. Bell allegedly forced an employee to get him through a restricted-access door, threatening to shoot her if she didn’t.

Bell allegedly fled with more than $60,000. Witnesses called 911 to report seeing a suspect drive away in a silver Volvo.

Officers spotted a car matching that description and pulled it over. Bell was detained, and a search of his car uncovered a black replica firearm, a little more than $64,000 in cash and clothing allegedly worn during the crime.

Police booked Bell for robbery and kidnapping. After reviewing video evidence, LAPD Det. Christian Mrakich, with the Robbery-Homicide Division, found that the suspect description and method of operation “was similar, if not identical to the October robbery incidents,” according to a search warrant request.

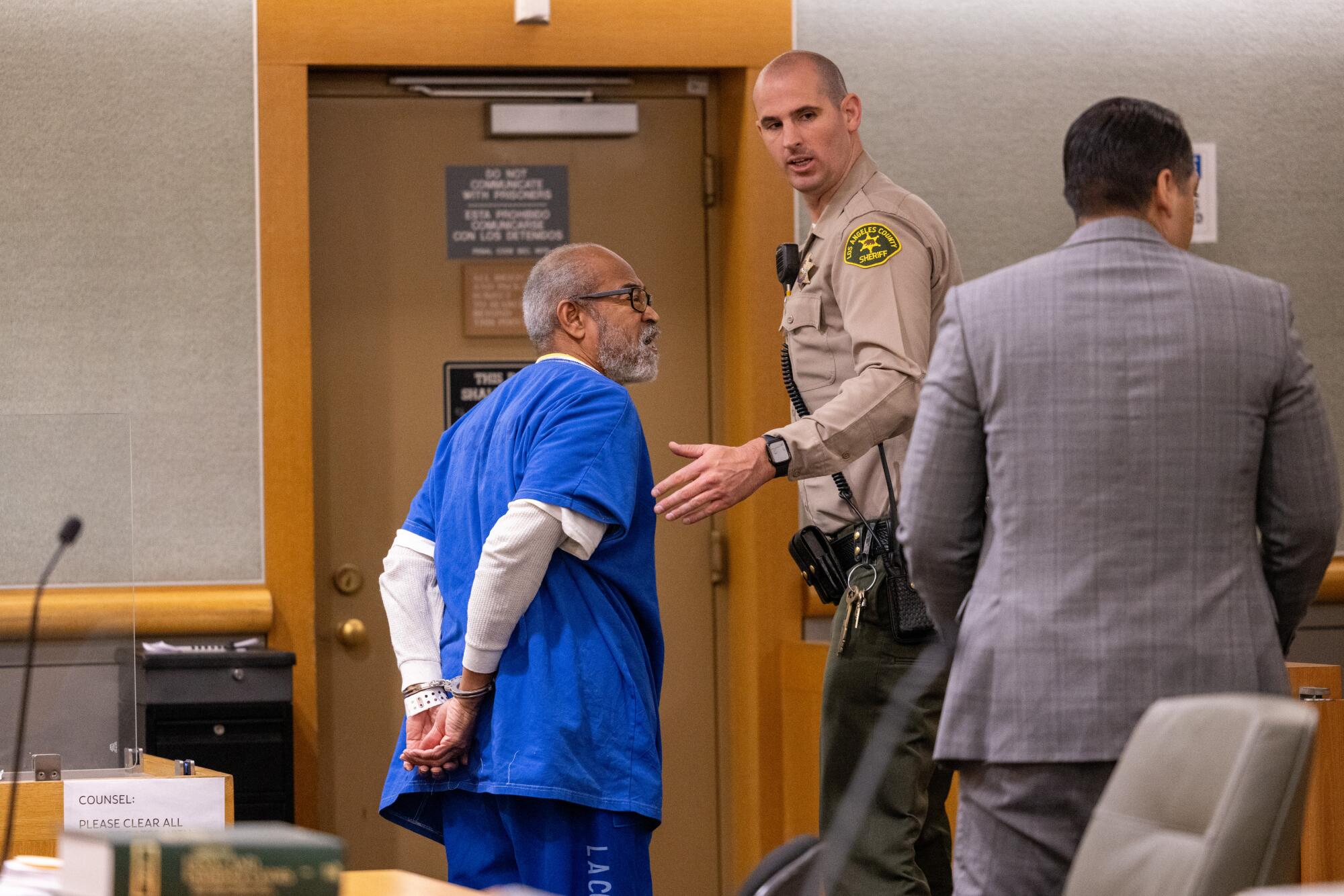

Bell is facing a variety of charges, including second-degree robbery, kidnapping, criminal threats and attempted second-degree robbery.

Harvey Wicker, 56, said his uncle was there for the family after his mom — Bell’s oldest sister — died in November.

“I just didn’t think he’d do this,” Wicker said.

Day told The Times he was shocked and saddened to hear about Bell being rearrested.

The lead facilitator for Goodwill New Beginnings reentry services in Indianapolis, Day said he hasn’t spoken to Bell since around 2000. But, he said, he still has “a level of respect and love for him, no matter his decisions.” Day declined to go into details about Bell, not wanting to betray the older man’s trust.

“I have no idea why Bruce did what he did. I have no idea what state of mind Bruce was in when he got out of prison, or what state of mind he was in when he got arrested for this bank robbery,” Day said.

“I do know this: A lot of us who live that lifestyle — that hustler, criminal, gangster, whatever you want to call it, lifestyle — a lot of times we get at a point in life to where we just say, ‘This is gonna be me for the rest of my life, whether I’m in prison, whether I’m dead, or whether I’m alive or out in the streets.’ Especially when you try to do something different and you’re not successful, or you fail at it, or people reject it.”

“I’ve had friends and I’ve had associates that they were in and out of prison until they died,” Day said. “And every time they got out, they went straight back to doing what they were doing before they went in or they came up with a different hustle.”

“I think,” he said, “sometimes we get stuck in that.”

::

Sitting recently on the other side of the glass partition in the downtown Men’s Central Jail, white streaked Bell’s beard and he was stooped with age. He looked more like a kindly grandfather than a serial bank robber.

He wouldn’t talk about the crimes he’s currently accused of committing, only the ones of which he’d been convicted.

Authorities said his past crimes were violent because he wielded a gun, but Bell stressed that he never used violence. He said he’s been clean now for more than 30 years and has a learning disability.

Perched on a stool, dressed in a jail-issued blue uniform, Bell seemed to take stock of his situation.

“I didn’t think,” he said, “I’d get caught up again.”

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.