CHP fired nearly 60 ‘less lethal’ rounds during one UCLA protest, new report shows

- Share via

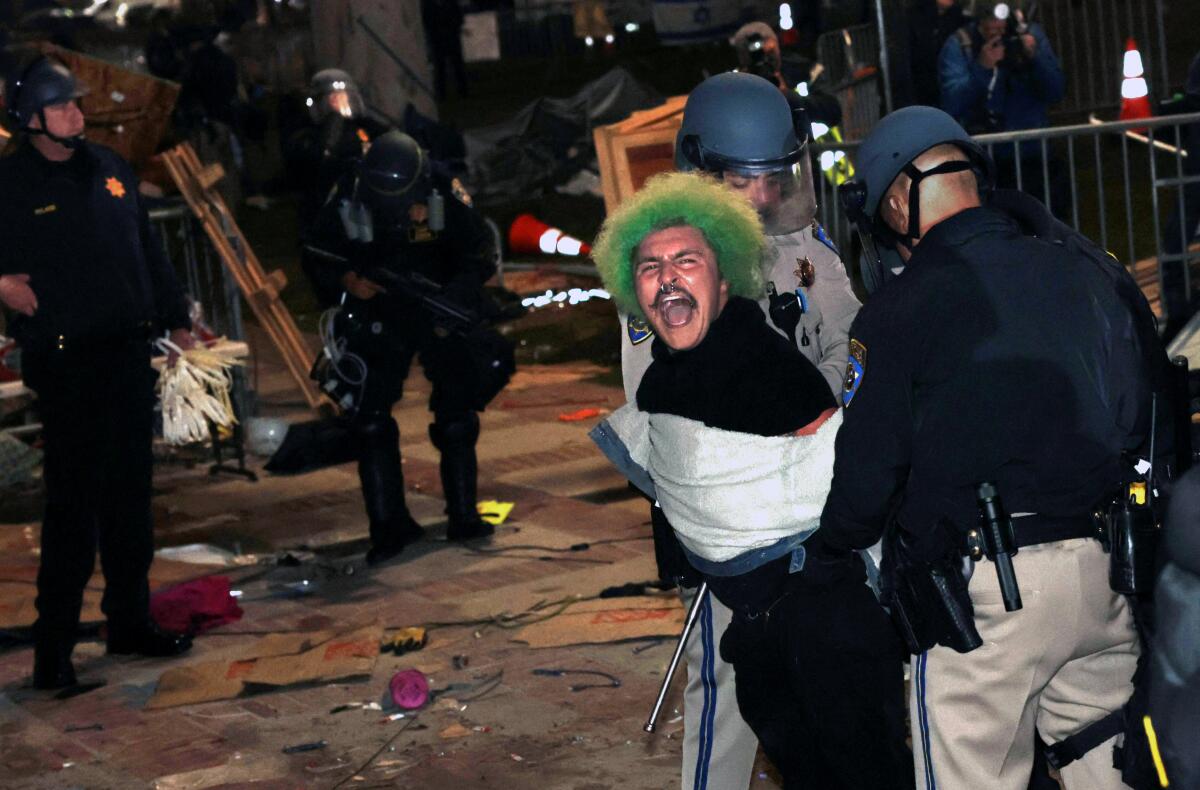

California Highway Patrol officers fired nearly 60 “less lethal” projectiles at protesters while clearing a pro-Palestinian encampment on the UCLA campus in early May, the agency disclosed in a new report this week.

The CHP denied claims made by protesters that officers fired indiscriminately into the crowd, which is illegal in California, and said officers were defending themselves. Two hundred people were arrested.

Although there has been no formal tally of the number of protesters injured, reports of students and others being wounded by police projectiles — being shot in the head, or having a finger badly mangled — began spreading immediately on social media amid the clashes.

Here is what we know about the last couple of weeks on campus, based on interviews, recordings, social media and documents.

Carol Sobel, a longtime civil rights attorney who has helped lead legal challenges to such weapons for decades, said it was no wonder protesters reported being badly wounded at the event, given the weapons’ widespread use.

“Sixty is a really large number,” she said of the rounds fired.

It’s also “really easy to miss” targets, and instead hit bystanders, in fast-moving and confined protest crowds like the one at UCLA, Sobel said.

In the early morning hours of May 2, the report said, officers assigned to several different CHP “special response teams” arrived at UCLA to begin clearing a large encampment. Over the next five or six hours, they fired 33 beanbag rounds from 12-gauge shotguns and two dozen 40-millimeter “direct impact” rounds, the agency said.

The agency said officers used the weapons after being “met with assaultive resistance,” including “multiple protesters throwing items, such as frozen water bottles, bottles containing urine and other unknown fluids, full 12 oz soda cans, pieces of plywood, wooden poles, and various sized fire extinguishers (full and emptied).”

It said officers “were also sprayed with fire extinguishers and other unknown chemical irritants, causing temporary blindness and difficulty breathing.”

As incendiary claims ricocheted across group chats and were amplified online, a crowd converged on UCLA and violence ignited when police left the scene.

It said officers used the weapons only after announcing they would and repeatedly issuing dispersal orders. They said officers fired rounds only “when they identified specific subjects assaulting officers,” and that at “no point” were the weapons “fired indiscriminately in the crowd.”

Independent accounts from the scene and reviews of video, including by CalMatters and The Times, found officers did shoot into crowds, and aimed weapons at parts of protesters’ bodies that they should not have.

UCLA was one of several flashpoints of unrest last spring, when students across California and the nation stood up encampments on their college campuses in protest of Israel’s escalating war on Hamas — and its devastating impact on average Palestinians.

As the encampments grew and complaints about them increased, including from Jewish students and organizations, campus officials began calling in police to clear them. The CHP was one of the agencies to respond under mutual aid agreements between law enforcement agencies across the state.

The CHP report was the first of its kind to be filed with the California Department of Justice under a state law passed in 2020 amid that year’s unrest.

Police badly wounded people with projectile weapons at the George Floyd protests and the Lakers’ NBA title celebration in L.A., spurring a mountain of lawsuits — which have cost taxpayers millions and still aren’t fully resolved.

Lawmakers in Sacramento responded by passing a measure barring the use of projectiles at protests except in instances where an officer has to “defend against a threat to life or serious bodily injury,” or “bring an objectively dangerous and unlawful situation safely and effectively under control.”

The law mandates that specially trained officers may only use the weapons after deescalation tactics have failed and “repeated, audible announcements” of their impending use have been made.

Even in those justified situations, such weapons can only be used against people “engaged in violent acts” and “in a manner that is proportional to the threat and objectively reasonable.” They can never be “aimed indiscriminately into a crowd,” or “aimed at the head, neck, or any other vital organs,” or used solely because a protester is violating a curfew, has made a verbal threat, or is simply not complying with a police order.

Officers must render prompt medical aid to anyone they injure. In addition, law enforcement agencies must summarize any use of such weapons at a protest in reports to the Department of Justice — usually within 60 days.

The Times requested such reports from various campus protests in the spring. This week, Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta’s office posted a link to the one-page CHP report.

The University of California shelled out an estimated $29 million to handle this spring’s protests over the Israel-Hamas war, with 90% of the costs going toward law enforcement.

The continued use of the weapons has alarmed some medical experts.

Dr. Linden Doss, an ophthalmologist and oculoplastic surgeon, has operated on people wounded by such projectiles in the past — reconstructing eye sockets and eyeballs. He said critics of the weapons “understand that there has to be ways that police defend themselves,” but projectile launchers are “far more damaging from a medical perspective” than is acceptable for “protest quelling.”

Dr. Rohini Haar, an emergency room doctor and adjunct professor at UC Berkeley who has researched the use of projectile weapons nationally with the organization Physicians for Human Rights, said the dangers of such weapons at protests are “not hypothetical,” but well documented over decades.

“At short ranges, they hit as hard as live ammunition, and at long ranges you cannot really aim or target them — so at neither of those ranges are they safe,” she said. “They really have no role in civilian policing, and I would say that’s even more important to underscore on college campuses.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.