- Share via

It was just a few weeks ago that Twitter, or X as it’s now annoyingly called, was once again in the throes of the dreaded D (Discourse) about the highly sensitive I (Identity) after the trailer for the new Disney animated series “Primos” made the rounds.

Created by Natasha Kline, the series centers on 10-year-old Tater Ramírez Humphrey, a Mexican-American girl whose 12 cousins move into her family’s home in Los Angeles for the summer.

Among the criticisms the series received was the main character’s poor Spanish — that it plays into stereotypes by having that many Mexicans under one roof, and the series’ yellow coloring, which is often applied to films and series depicting Mexico.

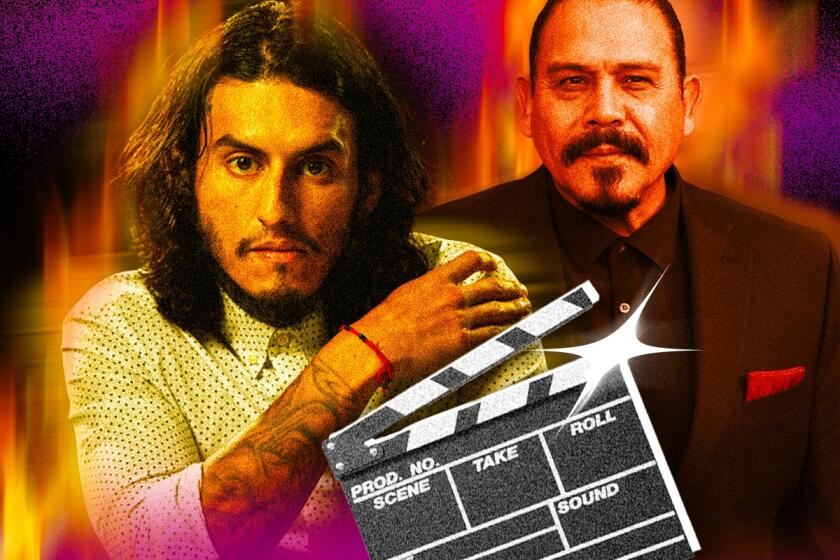

Why playing the stereotypical Latino role as a criminal is not a problem for some Hollywood actors.

Kline responded via Instagram, calling the backlash “traumatizing” and noting that the series is based on her actual life — the choices were intentional because they spoke to her specific experience. “It made me doubt myself, my project, my intentions,” she wrote in an illustration. In another illustration, she depicts a character being burdened by the words “you don’t count, you aren’t enough, you don’t have the right” and saying “God, I can’t carry anymore.”

As storytellers, Latinx creatives are dealt an impossible task. While the old adage says “the specific is universal,” it often seems like that doesn’t apply to Hollywood’s Latinx television writers, who are tasked with carrying the experiences of Latines from 33 countries, with differing types of Spanish and levels of Spanish-speaking abilities, who are at varying points of connection to their country of origin.

That doesn’t begin to account for the many other identities and experiences a Latinx person may hold, like being queer, trans, Black or Asian and therefore not “looking” Latinx. Hell, this article will likely receive numerous angry responses just for its use of the term Latinx, despite it not being a term enforced on anyone who doesn’t want to use it.

An exploration of marketing terms like ‘200%’ and how that’s shaped our identity.

Being Latinx encompasses so much. As many constantly have to repeat, we’re not a monolith, which means we don’t always agree. We may contradict each other.

There is no one way to be Latinx. And yet personal experiences that don’t align with an innumerable online majority are constantly invalidated as being inauthentic. As a result, Latinx writers and showrunners are tasked with carrying the invisible weight of representation that places them in a major conundrum with high personal and professional stakes. And so it begs the question: What makes a show Latinx?

The word “authentic” has been on Judalina Neira’s mind a lot lately. “There’s so much pressure to prove your bonafides as an authentic Latino,” says the Puerto Rican and Ecuadorian writer and producer, who’s worked on “Daisy Jones & the Six,” “The Boys” and “The Horror of Dolores Roach.” “And it’s made me question, well, what is an inauthentic Latino? If you are Latino, and you have an experience, you have an authentic experience, right? There seems to be this measuring stick out there in the world, and I don’t know who’s doing the measuring.”

Ask pretty much any Latinx person in the U.S. and at some point they’ve had to wrestle with questions around their authenticity — if they’re a real Mexican or Dominican or Peruvian and so forth. If your Spanish is broken or non-existent, forget it. Jalapeños make your tummy hurt? Prepare to have a woman emotionally de-board an airplane because you’re not real. You dance like Elaine Benes? Hmm, questionable. You reference “Seinfeld” instead of “El Chavo del Ocho” when it comes to herky-jerky dance moves? Outta here. You use the term “herky-jerky”? Now you’re asking for it.

“It’s like the expectation is to make the Latinx experience universal, but also specific to the point that every single person feels included. That’s just not possible,” says Sierra Teller Ornelas, the Indigenous and Mexican writer who created “Rutherford Falls” and also wrote on “Superstore” and “Happy Endings.”

“I actually wouldn’t know what necessarily makes a show Latinx because I don’t know what that exactly means, because it seems to mean a lot of things,” says Chris Estrada, the Mexican American comedian and co-creator of “This Fool,” Hulu’s critically-acclaimed comedy.

For Estrada, the term representation can feel burdensome, so he’s eliminated it from his creative process. “I just don’t think about it,” he says. “I just think about what I want to make and how I want to make it. I’ll just create something that feels authentic to me and maybe that’s it. … Somebody might tell me, ‘This Fool’ doesn’t represent me, and I go, ‘Oh, that’s good. That’s fine. It’s not supposed to. Maybe you can just like it.’”

That guiding principle feels like the most solid way to approach storytelling for Teller Ornelas as well. “I think, to me, that is the way around,” she says. “This is not to have a show that has a little bit of everything but to really fight for that specificity and reflection of your own experience. I think those seem to be the projects that are really, really thriving.”

It’s true that often when watching a Latinx show, it can feel like the diversity is being stuffed into a cast and plot. You want a gay and/or trans character, a gentrification and a deportation storyline, a slutty aunt, a homophobic uncle, someone grappling with their identity because they can’t speak Spanish. … The list could go on forever, because the issues and identities that are part of the Latinx experience are plentiful.

Diversity stuffing is understandable when you consider the severe lack of representation of Latinos in Hollywood — if you’re one of the rare Latinx creators who’s been given a shot at making a show, you want to make it count; you want to give people who are rarely seen a chance to be reflected on screen. When you consider the many obstacles showrunners face just to make a show, many of those obstacles being major points the WGA is attempting to negotiate within the ongoing strike, it can feel like trying to make a cake out of crumbs. It’s an unfair set of balls to juggle, and Latinx writers have to bear the burden of storytelling with far greater stakes than their white counterparts.

“How many Latinx-run TV shows have there ever been, right?” says Teller Ornelas. “Like less than 10? So it’s like, how much of the pressure is on us. It’s not the same as someone making a white show. There’s so many other shows, it’s not all on you to make a show that represents everyone and you can breathe a lot more when there’s a lot of other shows.”

And the fact is, there aren’t. Latinx writers are rarely given the chance to make and run shows, even if they’re at an experience level that makes them more than poised to do so. Instead, they end up repeating levels, struggling to get to the showrunner level. “I think that writers of color, and this is not anything controversial to say, are often just given less benefit of the doubt,” says Teller Ornelas. “I think we’re made to perform at a level that is just kind of higher than other people.”

Showrunners also have to deal with notes from studios and executives who, anyone in TV can tell you, don’t always get it. And no one, not even the most seasoned, respected, hit-making showrunner is immune from notes. Take into account the severe lack of Latinx executives at that level, and what that can mean when it comes to the notes that are given.

“We’re all navigating so many constraints very frequently, working with studio and network executives who don’t come from the same cultural background as us,” adds Neira. “And so trying to find shared references and a shared understanding and navigating the notes process means making compromises in places frequently.”

That being said, Teller Ornelas and Estrada both said they had a fairly smooth ride when it came to this issue. That’s not to disregard Neira’s experience but to illuminate that nothing is one way all the time, and creators are working with a different set of circumstances depending on many factors. That also makes things tough to navigate when the field changes constantly.

The reality is audiences and executives alike know what a Latinx show has been in the past; what types of shows have been greenlit or have found success; how they looked and sounded: that yellow filter, the prerequisite Flamin’ Hots jokes and Selena reference; the abuela clutching her rosary. Typically, they’re family comedies or crime series. Most often, they’re centered on the Mexican American experience, arguably because that’s a point of reference decision makers have when they live and work in Los Angeles. Both genres can easily veer into stereotypes and tropes that tend to plague any Latinx-centric series. Many of the tropes end up becoming a mechanism from which Latinos explain our very selves and our culture, which arguably reinforces the notion that there’s only one way to be authentically Latino.

‘When I first started playing folk music, people would look at my cowboy boots and be like, “Wow… so how did that happen?” ’

“I didn’t want to talk about being Latino, not that I don’t think those things are interesting,” Estrada explains. “But I don’t have chancla jokes. I don’t do stand-up in Spanish or I don’t do it in Spanglish. There’ll be a context for who I am just by how I present myself.”

But we also can’t forget whose stories are being left behind.

“I am Black, and I would say that when people talk about representation of Latinos, to me, having grown up in Latin America, the typical Latino is overrepresented,” says Santa Sierra, a Dominican writer and producer who’s worked on “Power Book III: Raising Kanan,” “Vida” and “Narcos.”

Latinx audiences demand more from their shows and are tired of being made into caricatures, especially by our own people. And while criticism is fair and necessary to creating understanding and combating erasure, it can feel like an unwinnable battle when anything even vaguely resembling a Latinx show can feel like it’s being held up to the measuring stick of Latinidad. Very few shows have mostly escaped this reality, finding support from critics and audiences alike. Among them are “This Fool,” “Los Espookys,” “Primo” (Full disclosure: I’m a writer on this show, but I swear I’m saying it because it’s factually true), “Vida,” “Gentefied” and “Gordita Chronicles.” That four of the shows on this list have been canceled also says a lot.

“I don’t think there’s a checklist for what makes a show Latino,” says Sierra. “I’ve come to believe that the constant search for an answer makes it seem like we’re so different as people that we’re hard to relate to. And it makes us seem that our lives, relationships, experiences are not universally relatable.”

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.