- Share via

Latinidad is an ever-expanding concept, but it has not often made space for the Garifuna people who come from various regions of Central America. In Los Angeles, the Garifuna are working hard to preserve their culture and help others learn about their little-known history in Latin America.

Welcome to GAMOLA.

The Garifuna Museum of Los Angeles operates out of a house in South L.A. that was built in 1911. It opened in 2011 with the help of Rubén Reyes, who saw how important cultural conservation was.

Reyes was born in Honduras and moved to the Garifuna village of El Triunfo de la Cruz in Honduras when he was a young boy. There he learned the Garifuna language and began exploring the culture. In 2012, he was the co-director and co-producer of the film “Garifuna in Peril,” which showcases the culture and people.

In 1635, Spanish ships that were carrying enslaved African people were wrecked near the coast of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in the Caribbean Sea. Survivors from the wreck were able to escape and make a life on the island. They settled among Indigenous Arawak and Carib Indians, which resulted in the Garifuna culture and language.

After the island was invaded by the British in 1763 and many Garifuna people faced imprisonment and starvation, a large population was exiled to Honduras. From there, Garifuna people began migrating to other nearby countries. Most Garifuna people continue to live throughout multiple countries in Central America including Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala and Belize.

Bootsy Rankin was born in Belize in the town of Dangriga, and grew up in a Garifuna household with his mom and three sisters. He attended Methodist schools and was a part of the choir. After graduating from high school, Rankin struggled to find a job. His mother decided to send him to the U.S. by way of Mexico.

When he arrived in Los Angeles, he realized he did not have a deep understanding of his own culture. He was not fluent in the Garifuna language and did not know much about his Garifuna ancestry. Once he started learning, he was hooked. Rankin heard about the GAMOLA and soon learned there was a Garifuna community in L.A.

“Once I get here in the United States with so many different tribes and everybody else’s ancestors, I decided, ‘You know what?’ I’ve got to find out who I am and my identity,” Rankin said. “I had to reflect back on my country, my people and my roots.”

At GAMOLA, he met one of the individuals helping to run and facilitate the museum. Cynthia Lewis, who is Garifuna, has been with the museum since its opening. Her mother was born in Honduras but raised in Guatemala and her father was born in Costa Rica. Both of her parents grew up speaking primarily Spanish and they did not learn English until they came to the U.S. in 1944.

Lewis explained in order to adjust to their new lives, her family had to change their way of life and assimilate to customs in the U.S. That meant letting go of their cultural identity. She now works at GAMOLA to ensure the Garifuna people and culture are celebrated, not marginalized.

‘I was ashamed to be from Mexico but profoundly proud to be born in Oaxaca. Until that night in Miami.’

“My dad, he did not want us to have an accent because of the way the country was going, ‘You’re in America, you speak English,’ ” Lewis said.

Lewis said that Belize has worked to help the Garifuna culture grow. She said that in other countries like Honduras there seems to be prejudice among different communities, which often leads to the exclusion of Garifuna people.

Lupe Fortune, who was born in Corozal, Belize, said that GAMOLA has helped her connect to who she is and has allowed her to meet other Garifuna people. She started going to the museum only a few months ago and said it’s an important part of the community.

“I’m learning and it’s truly informative and I would love for it to just spill out into the communities,” Fortune said. “It’s a lot to learn, and it’s sad because it’s right here and people don’t even know ... that this exists here.”

Fortune’s mom was born in Mexico and her stepdad was from Belize and was Garifuna. Her family spoke Garifuna and she could understand it but was not fluent in the language. She said that in the U.S. she would be treated differently for speaking Spanish and having a darker skin tone.

Rankin, Lewis and Fortune all spoke about how they did not start exploring their culture until they were older because of the generational assimilation. They mentioned that when their parents arrived in the U.S., they were treated differently for their cultural identity.

They believe the lack of knowledge and education about the Garifuna culture has caused misconceptions.

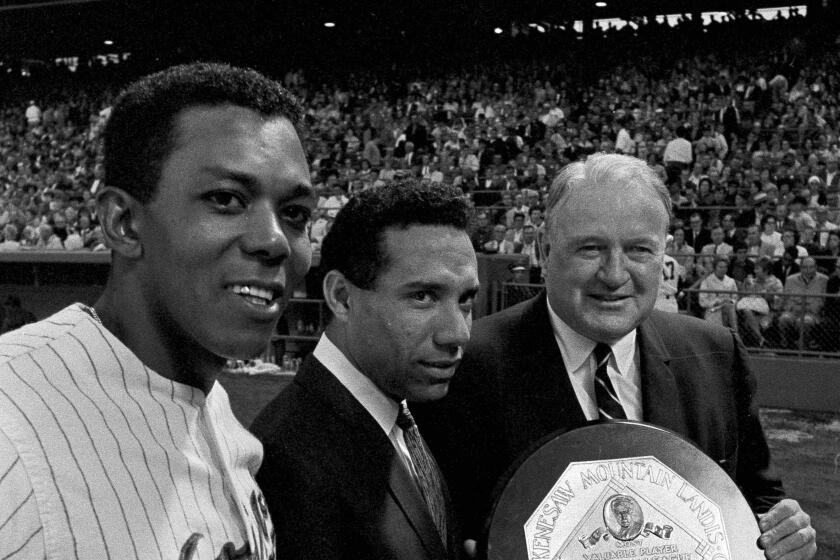

Zoilo Versalles and Tony Oliva were teammates on the Minnesota Twins. Both players were involved in a historic MVP race that would crown the first Latino MVP in the MLB.

“They would say we were warlike,” Rankin said. “That was the perception that was thrust upon us back in the days because we were so resilient that we didn’t want to be enslaved. So we fight, we fight, and we fight for years and years against the British and French.”

The goal of the museum, and those involved in it, is to uplift the Garifuna culture and educate L.A. about the history of the people.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.