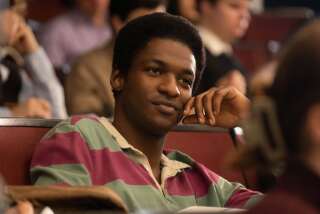

Yahya Abdul-Mateen II finds his creative space as Bobby Seale in ‘Chicago 7’

- Share via

Whether you’ve caught him in “Aquaman” (as Black Manta), “Watchmen” (as Doctor Manhattan, a role that won him an Emmy in September), or the new “The Trial of the Chicago 7,” in which he plays activist and Black Panther cofounder Bobby Seale, Yahya Abdul-Mateen II is a force to be reckoned with. The Envelope caught up with him recently to discuss representing Seale, taking up space, and portraying powerful Black presences on camera.

You grew up in Oakland, Calif., which has a lot of history with the Black Panther movement — so were you steeped in Black activism before “Chicago 7”?

Conversations about activism in my home were about being aware of the world and being able to educate yourself in order to make your own opinion. My father encouraged us to think twice and to read and not take things at face value.

In “Chicago 7,” Bobby’s kind of living his own movie-within-the-movie, which made me want to see his movie. Did you feel that, too?

Everyone has their own story, and you’re right on about that. A lot of those figures in the film, they knew each other and interacted outside of the courtroom. Bobby was in prison, and Bobby was a Black man. He was on trial without representation. I think Bobby’s experience was a very lonely, singular, isolating experience.

And at one point, Seale is bound and gagged in court. Of course, you’re playing a role but — did that tap into a deep personal place for you?

The first thing I wanted to do was speak up for Bobby Seale. But also know that as a Black man, I speak from my own legacy. So I knew this was less about me and my own anger but more of a historical anger and a historical effort to silence and beat and gag the voices and aspirations of Black men in this country. I didn’t have anger; I felt pride and responsibility but also shame. Even in an acting exercise, you feel the eyes on you, and you feel what a heinous act like that is designed to do. It was designed to break [Seale’s] spirit. The fact that it didn’t, it made me more proud to represent Bobby Seale in that moment.

Your name is somewhat uncommon here. How do you suppose it shaped you, growing up?

Had I grown up in Egypt or the Middle East, I’d have a very common name. It would be “John.” Did you know that? I remember being introduced to class in elementary school and — every single time — they’d laugh. But I like to think I carry the legacy of my father, and I want to carry his name. I look at my name with a lot of pride. If anything, my name has helped me stand out. I wear it like a badge of honor.

You were studying architecture before getting into acting. What appealed to you about that other possible career?

My father was a construction worker, and I always wanted to be like him, and I was artistic. What I loved about architecture was that I could create an entire world. There was something about having creative autonomy, to put a spin on an idea and make my own impression in the world. Once I found acting, I found I could take up space with my body, my voice, my presence, and that suited me very well. It’s a natural part of my own personality that gives me the appetite to take up space.

This society makes it hard for Black men to exist, much less exercise power, but you regularly inhabit super-powerful characters. On some level, is that satisfying? Do you think it signals to viewers that power comes in all shapes, sizes and colors?

Back on that theme of taking up space — we’re living in a time when art, when done right — Black creatives are not afraid to take up space. It’s more than “we’re not afraid”; it’s that we’re going to demand to be seen. We’re beyond the age of asking for permission. The Black Panthers weren’t asking for permission to protect their neighborhoods. I hope and believe we’re moving into a place in art and film where we’re taking up the space that is owed to us. We’re taking conversations that usually happen indoors and putting them out for the public to witness and digest. And if we continue to do that, then someone else will grow up knowing there’s a real pathway for them, and that pathway doesn’t involve a compromise of one’s identity.

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.