Review: Vendela Vida’s ode to teen strife could have been a great San Francisco novel

- Share via

On the Shelf

We Run the Tides

By Vendela Vida

Ecco: 272 pages, $27

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Vendela Vida’s new novel, “We Run the Tides,” unfolds in 1980s San Francisco, a city in recovery from the drug-addled 1960s and 70s. But in the Sea Cliff neighborhood that Vida’s narrator calls home, the counterculture’s trail is faint: Palatial homes of multigenerational San Franciscans are flanked by those of the new rich, and you can bump into Robin Williams in his “Mork & Mindy” phase at the local comic store.

“We know the towering brick house where the magician Carter the Great lived,” writes Eulabee, 13 at the time but now nearing 50. “We know that Paul Kantner from Jefferson Starship lived or maybe still does live in the house with the long swing that hangs above the ocean.” Eulabee and her friends scramble down the cliffs to beaches “cold, windswept, full of fishermen and freaks,” a ragged margin where other San Franciscans build fires, smoke dope and shoot up. It’s a kind of fractured fairyland and with the hypervigilance of teenage girls, they know that underneath the glossy surface of Sea Cliff lies trouble — suicide and business failure, drug use and sexual voyeurism. “Everything ugly is hidden.”

The setting feels authentic, with good reason: Vida lives in the San Francisco area and grew up there. Like the author, the narrator has a Hungarian father and a Swedish mother. And, like Eulabee, as a teenager, Vida loved to tell lies. In 2011 she told the Guardian, “I lied all the time. I used to make up stories about everything.” Then Vida recounted the true story of an outrageous lie and its consequences for her and her parents. That lie is recreated point-by-point in her new book.

Vida left San Francisco for college, worked at the Paris Review, met her husband, Dave Eggers, and eventually moved back to her home town. Today she is West Coast literary royalty; she cofounded the Believer magazine, helped Eggers create the 826 Valencia writing lab for young people and has published four earlier novels and one nonfiction book. But duplicity and its fallout are still on her mind. In “We Run the Tides,” Eulabee is an adept liar but her fibs are small stuff compared to the monster fabrications of Maria Fabiola, Eulabee’s friend and the social queen of Sea Cliff. “Separately we are good girls. We behave,” Eulabee writes. “Together, some strange alchemy occurs and we are trouble.”

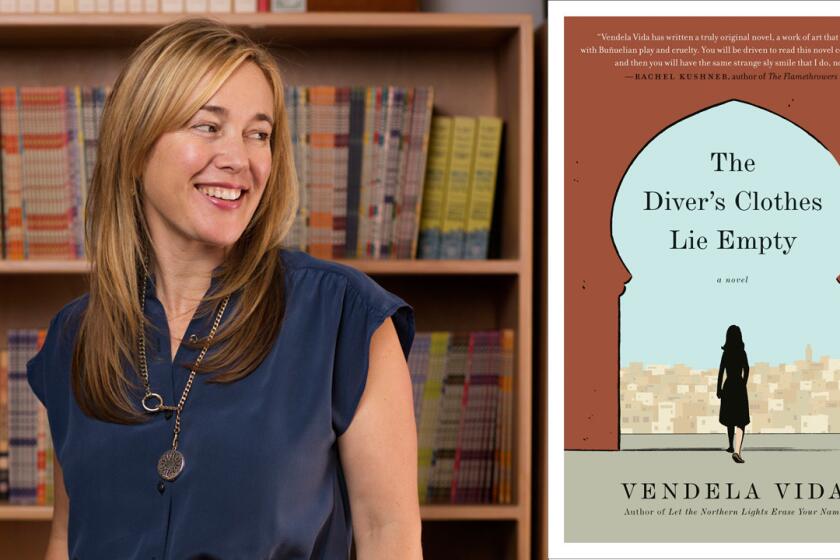

Vendela Vida has for more than a decade published novels centered on women in crisis.

Eulabee’s real trouble begins when she tells the truth. After she refuses to verify Maria’s false report of a voyeur loitering near their school, Maria, enraged, drops her, and her other friends get in line. As she falls from grace, “I feel like I’m on a boat tilting over in the wind — someone needs to leap to the other side to balance the weight,” writes Eulabee. She becomes the neighborhood pariah. In the depths of her misery, she secretly applies to boarding schools. Then Maria Fabiola goes missing. Eulabee seems to be the only person in Sea Cliff who doubts that Maria has been kidnapped by Russian gangsters — and the only person looking in places where she might actually be found. But other disappearances follow, including one whose consequences are all too real.

There is plenty to admire in this novel, with its echoes of J.D. Salinger and Margaret Atwood (“Cat’s Eye”). The hothouse atmosphere of Eulabee’s private school, the cruelty of adolescent girls, Eulabee’s commonsensical parents and the warmth of their family life in its Swedish traditions and frugal ways. With her mordant honesty and cracked wit, Eulabee is an engaging narrator.

The question is: Why does this novel fall a bit flat?

Perhaps the problem lies with Vida’s decision to focus on Eulabee’s point of view; we never quite get why Maria is such a prevaricating, manipulative control freak. She is a feminine archetype, the alpha female who bullies and lies to get her way, stunningly beautiful and fabulously rich, and everyone — parents, boys, classmates — adores her. But for most of the novel, Vida keeps Maria’s inner life hidden and so to some extent, Eulabee is shadowboxing an inscrutable opponent. What drives a girl who has everything, attention most of all, to want more?

The reader gets some answers in the last chapter when present-day San Francisco has been overrun by another kind of wealth and no one who grew up in Eulabee’s neighborhood can still afford to live there. “The streets of Sea Cliff are no longer ours,” Eulabee writes; her neighborhood now belongs to “the new San Francisco, to the tech giants, to buyers from abroad who, rumor has it, paid cash and bought the houses sight unseen.”

To be quiet in a prison, an incarcerated student once told me, is to admit you’re there.

Eulabee, now a translator, moved with her family to the more affordable margins of the city and it’s by chance that she meets her former frenemy at a literary festival in a Capri hotel. Only then does Vida reveal some of what’s behind Maria’s crumbling defenses and the extremes she will go to guard them. It is the best part of the book and leaves one hungry for a deeper, broader look at these two women, so different yet so alike, grappling with the consequences of their actions. I would read that book.

Gwinn, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who lives in Seattle, writes about books and authors.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.